We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

I didn’t know Brahms had written a serenade, much less two dazzling ones, when he was a younger composer. This is the Brahms that fascinates me right now: the winsome, delicate-looking, blue-eyed, golden-haired young adult, who left behind family to hit the road to tour musically and meet his destiny head-on.

You know the phenomenon: you hear some beautiful yet unfamiliar classical music being played on the radio, but you don’t have access to the details like its title or its composer. It stops you in your tracks because it’s so beautiful and fresh, and you mentally scroll through possibilities. Mozart? I had, after all, overheard the piece announced as “Serenade No. 2.” I knew Mozart had composed serenades, but this one sounded too Romantic-era to be Mozart. Dvořák? No. I knew all his serenades by heart. Grieg? Nope, his specialty was short lyric pieces. It never crossed my mind that it could be Brahms. It was too sunny and bucolic, too “pretty” for Brahms. Certainly for the aging, heavy-set, bearded man from all the images on CDs, albums and such that I’ve known since childhood. Mendelssohn, I decided.

Well, knock me over with a feather. It was indeed Brahms.

I didn’t know Brahms had written a serenade, much less two. Furthermore, this prompted a burning question: who was this Brahms?

Back when I was a kid, my dad enjoyed listening to classical music in the evening. He favored symphonic music and the German Romantics, so I grew up hearing LP recordings of, among other things, Brahms’s symphonies. I had sufficient knowledge about “my dad’s” Brahms, how enormous the composer’s artistry and musical legacy was. How he strove to emulate and honor the German masters before him, particularly Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. A composer of impeccable, beautifully structured symphonies, and more, that conformed to classical form. But… emotionally thrilling?

Why had “Dad’s Brahms” not stirred me? Why had it not gripped me and held me captive the way, say, Schumann’s music had? After all, they were both Romantic-era composers, and, further, Schumann was a mentor, advocate and close friend (for a regrettably short time) to the young Johannes.

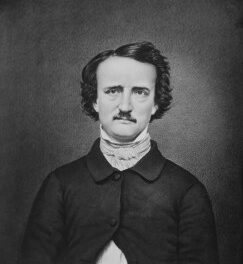

This was what my dad’s Brahms looked like:

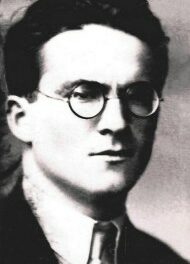

So back to my burning question of who was the other Brahms, he who composed the serenades? Turns out, he looked like this:

This is the Brahms that fascinates me right now: the pre-beard Brahms. The winsome, delicate-looking, blue-eyed, golden-haired young adult, who left behind family and teacher to hit the road in 1853 to musically tour with violinist Edouard Reményi and meet his destiny head-on.

More on the serenades shortly. First though, more on the young Brahms, born in 1833 in Hamburg to humble circumstances. His father, Johann Jakob was a freelance musician and when his son showed early interest in musical and displayed perfect pitch, he was thrilled.

Johann Jakob had always been a bit of a dreamer, a character and a risk-taker, with aspirations to move up in the world. Which might explain why, at the age of 24, he courted Christiane, a woman from a much more respectable family, who was, however, a spinster of 41 years. (Yikes! But apparently she had beautiful blue eyes.) Johann Jakob, while poor, was charming, gregarious and seemed genuinely smitten. Christiane surely saw this as her last chance at a family, as a wife and a mother. When he proposed, she said yes, and they married promptly. Within five years, she’d given birth to three children, the middle of which, born on May 7, 1833, was Johannes.

The family moved around frequently, living in cramped quarters, mostly in rough neighborhoods, with dark, dodgy streets and passages, close to the waterfront, sailors’ dancehalls and the like, but the family nonetheless thrived, particularly the bright, curious Johannes—called Hannes as a boy. Dad began teaching Hannes to play musical instruments at age four. He wanted the boy to focus on one that would allow him to have a job and career like his father—a bugle player in the local brass band as well as a fiddler and contrabass player here and there. But it was the piano the boy really wanted to learn. Johann Jakob resisted the idea, but Hannes was persistent in asking, year after year, and finally his father gave in.

Author and composer Jan Swafford, in his excellent book, Johannes Brahms: a Biography, charmingly describes what followed:

In 1840, Johann Jakob took his seven-year-old to the home of Hamburg piano teacher Otto Cossel. […] The studies began, and Cossel took to the boy. Delicate and blond, with his mother’s forget-me-not eyes, Hannes would show up for lessons sometimes barefoot, sometimes in clattering wooden shoes. He would sit his tiny form down before the big keyboard and attack it with a large determination. His progress was remarkable, but once again the strange obstinacy turned up, as though the child had some vision before his eyes that only he could see. Now he insisted to Cossel that he wanted to learn how to compose music, not just play it. But that would be another struggle, in due time: if the piano seemed impractical to Johann Jakob, composing was an absurd indulgence for anyone expecting to make a living at music.

After three years under Cossel, Hannes progressed to Eduard Marxsen, who’d been Cossel’s own teacher, Hamburg’s most famous and well-regarded musical figure, a notable pianist and composer. Marxsen was a traditionalist, who called the musical forms of the masters (sonata, theme-and-variations, rondo, fugue, etc) “eternally incorruptible.” It was Marxsen who, according to Swafford’s biography, “infused Brahms with that sense of traditional form, part technique and part religion. Brahms never strayed from that spirit, no matter how creatively he varied the details of the old design. From his apprenticeship on, all else but allegiance to the past and its procedures appeared to him as chaos.”

Hannes’s musical education was excellent and he was a willing, motivated student. But when you’re a boy from a poor family, education is a luxury. By thirteen, his father was insisting Hannes contribute to the family income by playing at waterfront taverns and local dance halls. By day he continued his studies and by night he worked as a pianist, into the wee hours of the morning, keenly aware of the depravity on display all around him in the form of drunken sailors, shrieking, overly willing women, everyone’s darkest impulses laid bare. While it helped the family financially, Brahms would later remember those early teen years as a dark, destructive blight on his psyche that forever affected him.

Finally his teen years and family dependence came to an end when, in 1853, Johannes embarked on an adventure as an accompanist to Hungarian violinist Edouard Reményi. While on their self-promoted tour, Reményi suggested they stop in Hanover to see his old classmate, Joseph Joachim, already one of their generation’s greatest violinists. Johannes and Joseph quickly became friends, a relationship that would last a lifetime. Through Joachim, and an ever-widening social and professional network, Johannes would also meet Robert and Clara Schumann that year, in Dusseldorf, and play some of his compositions for them. Both Schumanns—Clara was a renowned piano virtuoso who also composed—were wildly impressed, prompting Robert to pen an essay in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, that sang Johannes’s praises.

I have thought, watching the path of these chosen ones with the greatest sympathy, that after such a preparation someone must and would suddenly appear, destined to give ideal presentation to the highest expression of the time, who would bring us his mastership not in process of development, but springing forth like Minerva fully armed from the head of Jove. And he is come, a young blood, by whose cradle graces and heroes kept watch. He is called Johannes Brahms.

This catapulted the twenty-year-old Johannes into the limelight of the classical-music world, which surely scared the hell out of him. Excessive criticism can ruin a young artist of any medium. Excessive praise can do it even faster. Johannes was still so green and untested, and he knew it.

I could write an entire essay about Brahms and the Schumanns alone. About Brahms’s impassioned love for Clara Schumann through Robert’s decline into madness and consignment to a mental institution, and beyond. I could also write an entire essay about Brahms’s music and life through his “beard” years. (Factoid: he had a high voice that hadn’t deepened in adolescence, which he despised, and I can’t help but think the beard was something he relied on to look—and sound—less boyish.) Then there’s his Violin Concerto, which I’m crazy about. Another Brahms essay to come, I’m thinking. For now, in the interest of brevity, let’s fast forward.

In 1858, Johannes found lucrative seasonal employment at the court of Leopold II in the principality of Detmold, as a choral director and royal piano teacher (a position Clara Schumann had held, for which she recommended Johannes). In his spare time he’d been working on a piano concerto (the No. 1 in D minor), which was proving wildly difficult, too big and unwieldy and problematic. To ease the brain strain, he’d sketched out a serenade, a lighthearted, Haydn-inspired composition for “a small ensemble of winds and strings” that he wouldn’t have to take as seriously as the piano concerto. That summer he accepted an invitation from friends to visit them in Göttingen in July, not without reluctance, as he was preoccupied with his work—he always was—and was not a naturally sociable creature.

He needn’t have worried; the vacation turned out to be a delight. His friends, Julius Otto [Grimm] and Philippine, a married couple, had invited a local friend, a delightful young soprano named Agathe von Siebold, to join them, and the four of them spent an idyllic July basking in the warm sun, playing games, laughing and bantering, picnicking, and talking about music, playing music, listening to music. They were all of a similar age and this was something novel for Johannes, to be so sociable, carefree and laughing with same-aged peers. Best of all, romance bloomed between Johannes and Agathe—his first love (besides Clara, who was 14 years his senior, and his friend’s wife-then-widow, besides). This easier, more uncomplicated relationship with Agathe grew steadily grew in the months to follow. Returning home, the golden memories surely circulated through Johannes’s mind as he began working in earnest on the first Serenade in D major, orchestrating it beyond the original nine-musician ensemble he’d first composed. It grew big, even to the size of a symphony, and he considered, through discussions with Joachim, calling it a “Symphony-Serenade,” an idea he later nixed.

Time to give Serenade No. 1 a listen in its full orchestral version, which premiered in Hannover in March 1860. This one is performed by the Faust Chamber Orchestra at LSO St Luke’s, conducted by Mark Austin.

But first, a road map:

- The first movement is cheery, optimistic, with moments of thrilling excitement. Horns call, flute and strings reply, and the timpani makes everything all that much more exciting.

- The second movement is lyrical and sweeping, almost sounding like Dvořák. Then again, the younger Dvořák admired Brahms, who actually served as a mentor and advocate (a rare thing for the private, curmudgeonly Brahms).

- The third movement delivers flute, strings, horns in a lush, sweeping adagio that’s pensive, poses questions and allows the answers to waft down in their own time. It’s divine, transporting. The flute is given the final voice in the conversation, a sort of “yes, but …?” query that is allowed to express itself in a pure, singular way.

- A pair of minuets follow, with the interplay of strings and winds keeping it mild-mannered and pleasing, a palate cleanser of sorts after the intensity of the adagio.

- After a brisk, bright scherzo, the final movement, a rondo with a driving, propulsive rhythm, ultimately leads us to the serenade’s rousing conclusion.

What do you think? Are you as dazzled as I was? Have you ever heard of this work? I’m leafing through several of my classical-music reference books and many of them, even the comprehensive ones, don’t even mention the serenades. Wow, what a shame. Then again, Brahms was a master with a massive output and even he saw the serenades more as orchestration exercises, not aspiring to grandness so much as a cheerful, sunny respite from the intensity of his other music (like that cursed first piano concerto).

Here’s the version I hurried to buy within hours of hearing that initial Serenade recording (it was No. 2 I heard, but as much as I enjoy that one, I’ve grown even more enamored with No. 1. Buy it; you know you want to.

Secondly, if you want to learn more about Brahms, at a deep, comprehensive lever, I highly recommend Jan Swafford’s Johannes Brahms: a Biography, which you can purchase HERE. It’s as descriptive and engaging as a novel. Think James Michener-meets-Classical-Music.

Republished with gracious permission from The Classical Girl (May 2024).

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Images of Johannes Brahms are in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The “Prestation de serment de Léopold II” (1865) by Louis Ghémar is also in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News