We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

This week is the 150th running of the Kentucky Derby — thought to be the longest continuous sporting event held at one venue in the whole world. As I wrote a while back, it’s also the most anti-woke celebration on the planet, floated on an ocean of that most American liquid — bourbon whiskey.

But then, there is just a lot of great history and lessons to learn in the racing game, especially as it all tends to reinforce the conservative worldview. For example, we have the sad story of human greed and the late, great Arlington Park racetrack outside Chicago, in Arlington Heights.

At one time, Arlington Park and its environs, were considered on a par with Saratoga Springs, Del Mar, and even Ascot, England, as the host of a glamorous “summer meet” for the world’s richest people and their racehorses. That changed in the 1960s as the tracks owner, Marje Everett, ran afoul the deep corruption of the Illinois Democratic party, giving Gov. Otto Kerner stock options, presumably to get better race dates. The whole scheme was so blatant that both Everett and Kerner had reported it on their income tax returns, and Kerner, who by then was a sitting federal judge, was packed off to prison.

As other forms of legal gambling exploded the last two decades, Chicago particularly lost interest in racing and the track was sold to the McCaskey family, supposedly for a new Bears stadium. The Bears have one of the stingiest ownership groups in sports, always trying to get the local government to pay for everything. They wrestled with the Arlington Heights tax districts to give them massive abatements, as they promised to redevelop Arlington Park, but now, with Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, they got the sucker they were waiting for. They just returned their sights to the Chicago lakefront to get a massive government-funded stadium. Arlington Heights, played for suckers all along, will now see the McCaskey family make a bundle, as they sell off the race grounds for nondescript condominium towers.

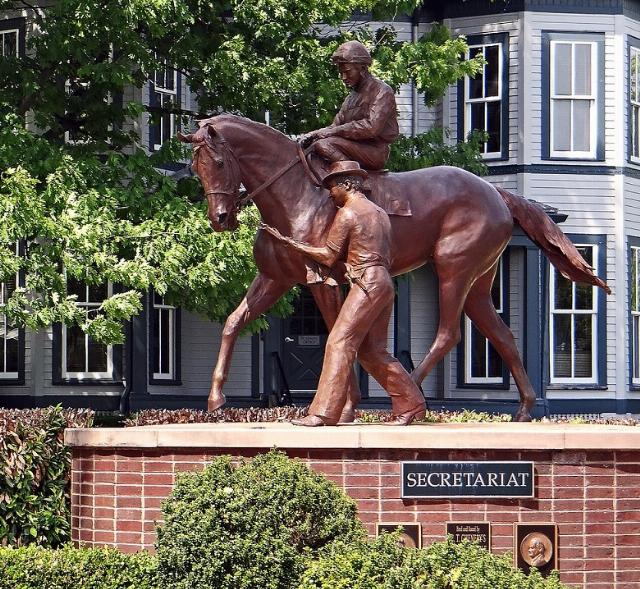

Of course, even the world’s most famous racehorse, Secretariat, has a backstory filled with greed and taxes. If all you know is the Secretariat movie, the real life story is much more interesting than the Disney fairytale.

It seems Secretariat’s owner, Helen Bates Chenery Tweedy (Penny) was anything but a nobody suburban mom. She was an East Coast blue blood and equestrian. Her dad Chris made a fortune after WW I on Wall Street, setting up suburban water and gas companies, and then in gas exploration.

It seems Secretariat’s owner, Helen Bates Chenery Tweedy (Penny) was anything but a nobody suburban mom. She was an East Coast blue blood and equestrian. Her dad Chris made a fortune after WW I on Wall Street, setting up suburban water and gas companies, and then in gas exploration.

As a New York insider, he was drawn to thoroughbred racing, buying back his ancestral farm in Virginia, which he was cagey enough to stock with only the best pedigreed mares; the kind his Wall Street buddies would breed to their champion stallions; often in two-year deals, as with Secretariat, without stud fees (or taxes) where each side got a foal. The Meadow Farm stable was very prominent for decades doing business this way.

Penny was well educated, one of the few women in her class at Columbia Business School and her Ivy League lawyer husband moved the family to Colorado as part of his extensive oil and gas work, and to be near the luxury Vail ski resort he helped develop. Secretariat’s owners were, to put it mildly, very rich.

The movies and books only hint at this, but apparently, the Chenery kids were not close, and none of them wanted to look after their father as he became infirm. Eventually, Penny grew bored with her Colorado husband and went back East to run the stable in the late ‘60s. Back then, New York sports media covered horse racing the way they now do the NFL. Penny wisely fired the old Meadow Farm trainer, who was apparently a crook. With better horsemen in charge, the stable thrived. Penny was a New York celebrity darling and played that game as well as anybody, including Donald Trump.

Unfortunately, even with all these smart rich people: Penny, her husband, her dad, and her brother — the World Bank VP — none of them thought to do some estate tax planning when it would have made a difference. When the accountants explained this, Penny’s siblings, who had no interest in racing, demanded she sell everything. Fortunately for her, a great race horse, not Secretariat, but Riva Ridge, came along, and won enough money to keep the place going.

Penny and her Kentucky breeder friends then set up a massive syndication sale of her promising new colt, Secretariat. Penny lobbied the race writers to vote Secretariat Horse of the Year in 1972, even though her other horse, Riva Ridge, had won the Kentucky Derby and Belmont, knowing it would help pump up the syndication price.

When as a three-year-old Secretariat turned out to be as good as advertised and won the Triple Crown, Penny set up an unprecedented barnstorming tour across the U.S. and Canada, with highly televised special races inaugurated just for him, like the Marlboro Cup sponsored by the cigarette company. Penny was the ultimate camera hog and would often battle Howard Cosell for control of the microphone when ABC covered a race.

That’s why Secretariat is so famous, 50 years after he retired. He was great, certainly, while also suffering some stinging defeats. But right at the apogee of the Television Age, his owner had seen to it he got more news coverage than a Moon Landing or Middle East war. You may see a faster horse, but never again one so well-known, thanks to all that publicity.

Under the syndication deal, Penny was to put “Big Red” out to stud, ending his race career at the close of 1973; and she also sold Riva Ridge for many millions. However, when her dad died that year, there was still a massive estate tax bill, and the family had to sell Meadow Farm.

You could say in the end, Secretariat won a lot of money and set a lot of records for his owners, but even he wasn’t fast enough to outrun the taxman.

Frank Friday is an attorney in Louisville, KY.

Image: GPA Photo Archive

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News