We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

The importance of George Ticknor lies in contrasts, which bring into relief another America. As an old Federalist who worked to undergird volatile American democracy with traditions, Ticknor and his Brahmin compatriots “wove a tapestry of conviction and hope, doubt and despair, which became a conservative testament.”

In July 1836, a European statesman and an ex-Harvard professor debated the merits of democracy and monarchy. George Ticknor listened intently as Klemens von Metternich lectured him across a small table piled with state papers. The Austrian Chancellor’s words profoundly impacted Ticknor. “During the whole time, from beginning to end, did not seem to take his eyes off my countenance,” he wrote in his journal. After that day in Vienna, the Bostonian became a Metternichian critic of democracy and revolution, and profoundly more pessimistic about the future. He represented the Boston Brahmin elite who, through all their warts, worked “to civilize Boston,” attain international cultural acclaim for “the Athens of America,” maintain standards against Emersonian barbarism, and create institutions to improve the education and literacy of all New Englanders. Before there was an Autocrat of the Breakfast Table, there was George Ticknor the Autocrat of Park Street: Harvard professor and reformer, Tory aristocrat and social arbiter, conservative Federalist, and father of the Boston Public Library.[1]

As a young man, Ticknor capitalized on the financial success of his Boston merchant father to become an independent man of letters. He and a young Edward Everett attended German universities in the 1810s learning French, Spanish, German, Greek, and Latin, as well as European literature and history, to prepare for Harvard professorships. Although Everett ultimately entered politics, it was Ticknor who charmed Europeans with his social graces and democratic touch. He was declared an American Lord Byron with his dark complexion and eyes, unkept black hair, and witty conversational skills, and made fast friends of the Continent’s leading intellectuals. Thomas Carlyle, Sir Walter Scott, Madame de Staël, and dozens of others fell under his spell and maintained a lengthy correspondence across the Atlantic. Ticknor became a Romantic idol. “Every door, however jealously guarded from ordinary intrusion, seems to have felt the magic of Mr. Ticknor’s ‘open sesame,’” the essayist Edwin P. Whipple observed. With a facility for adaptation, he populated European drawing rooms with equal finesse as chumming with earthy Iberian smugglers sneaking into Portugal. He also gained a reputation for bluntness, if occasion called for it. When the imperious Lady Holland informed him at a dinner party that New Englanders descended from English convicts, he answered icily that this explained why so many of her seventeenth century ancestors settled there. The exchange, which startled guests, foretold his coming role as Boston’s social gatekeeper.[2]

Upon return to Boston in 1819, Ticknor took up Harvard teaching and remained there for fifteen years. The students loved his lectures, Van Wyck Brooks reported:

They opened up vistas of adventure, unheard-of prospects for a poet’s life. And if, without wishing to spread the peacock’s feathers, he dropped, in those years to come, into reminiscence, he could unfold a world-panorama such as few in Cambridge had ever dreamed of … Here and there, as they followed his lectures, they were to catch a phrase of an allusion that opened up the picture. What patterns of the literary life the great professor, cold as he was, and distant, was able to place before them!

His tenure was stormy, however, as he conferred with Thomas Jefferson over plans for the new University of Virginia (Jefferson offered him a professorship, but Ticknor turned him down) and attempted to introduce German practices like electives, disciplinary departments, classes based on proficiency, graduate schools, and a dress code to the old Puritan college. Harvard (Ticknor himself was a Dartmouth graduate) was merely a prestigious high school for educating aristocrats, he complained, with students drawn more to rowdy Boston nightlife than books. But the push for academic reform caused a resentful backlash, including the opposition of close friends like Everett who preferred quietude to change. Ticknor’s bitterness became so acute that he began publishing with Philadelphia journals to spite Boston literati. A friend pleaded, “We are all laborers in literature as well as politics for the honor of Old New England … There is no harm in pouting a little occasionally provided you make up before you do each other or the public any mischief.” By 1835, fed up with Cambridge, he happily resigned and relinquished his professorship to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Everything Ticknor advocated came to pass at Harvard and elsewhere after the Civil War, although he never lived to see it. “It is hardly too much to say that the germs of those modern phases of learning which has distinguished Harvard College during the last thirty years, are discernable in the plans which George Ticknor cherished thirty years before,” Barrett Wendell (who knew him) wrote in 1900.[3]

While at Harvard, Ticknor purchased a new home at Nine Park Street (“Ticknor’s Iceberg,” critics dubbed it), a grand four-story Federal mansion adjacent to the Massachusetts State House. In its stately environs, Ticknor and his wife Anna Eliot “could see Boston Harbor and smell the east wind coming in with the tide in the summer or, in the winter, watch the snow falling on the elms lining the mall of the Boston Common.” The upstairs library, dominated by a portrait of Sir Walter Scott over the fireplace and stuffed with mementos of European travels and 14,000 books, became the most hallowed in the city. Ticknor’s Spanish collection alone was the world’s third most valuable outside Spain itself, comprising over 4,000 books and pamphlets which he used to write his three-volume 1849 History of Spanish Literature. Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the few younger writers welcome in Park Street’s inner sanctum, recalled: “Mr. Ticknor has a great head, and his hair is gray or grayish. You recognize him, at once, the man who knows the world, the scholar, too, which probably is his more distinctive character, though a little more under the surface … His library is a stately and beautiful room, for a private dwelling, and itself looks large and rich.” Unique and rare as his collections were, Ticknor operated it as a massive lending library and generously sent books to friends and students all across New England.[4]

Nine Park Street also became Boston’s social clearing house and Ticknor, “the high priest of the Brahmin caste,” so successfully replicated European manners that visitors swore they were in London. The city’s intellectuals, writers, and politicians coveted invitations to Ticknor dinners and European visitors decorated the gatherings. “I have never seen any society equal to what was there, great cordiality shading off into degrees of welcome, high-bred courtesy in discussion and courtly grace of movement,” one guest recalled. He also opened these dinners to all, the only qualification being discretion of taste rather than class.[5]

Herein lay the harder edge of Ticknor’s hold over Boston, sometimes called “Ticknorville” in the antebellum years. Those welcomed inside Ticknor’s home were welcome everywhere. Those uninvited were blackballed across the city and that yearning for dinner invitations and library drop-ins became the disciplinary arm of Ticknor. Democrats (with the notable exception of Nathaniel Hawthorne, whom Ticknor greatly respected), reformers, abolitionists, and religious liberals were all exiled from his rooms. They returned his hate. The anti-slavery minister Theodore Parker called him “the arch devil of the aristocracy” who exhibited “the Tory temperament.” His former Harvard student Charles Sumner, found the doors of Brahmin Boston closed to him and blamed Ticknor, “the personification of refined idleness.” Transcendentalists earned particular scorn (a “wild sort of metaphysics,” he called their philosophy) and he deprecated Emerson’s angst over the lack of American cultural independence. “It was a moral and political attitude, then, which made a writer American: not his style, his subject, his literary tradition,” historian Martin Green explained. Ticknor defended social standards to a friend in 1848:

The principles of [Boston] society are right, and its severity towards disorganizers, and social democracy in all its forms, is just and wise. It keeps our standard of public morals where it should be, and where you and I claim to have it, and is the circumstance which distinguishes us favourably from New York and other large cities of the Union, where demagogues are permitted to rule, by the weak tolerance of men who know better, and are stronger than they are. In a society where public opinion governs, unsound opinions must be rebuked, and you can no more do that, while you treat their apostles with favor, than you can discourage bad books at the moment you are buying and circulating them.

For Ticknor, it was the duty of literary elders to protect common sense and “he never lost the conviction that the writer should be the guardian of the commonwealth.”[6]

Park Street’s social regimen gave Ticknor a reputation for hardness, some of it legendary. His close friend the historian William H. Prescott once wrote him a letter of introduction before a European trip, adding among other phrases “warmth of heart,” and afterwards crossed it out. In conversation with strangers, he studied them to see if their choice of dress matched their decorum. “Ticknor’s manners did not impress the public as engaging,” Wendell remembered. “His dignity seemed forbidding; his tongue was certainly sharp; to people who did not attract him his address was hardly sympathetic; and his social habits, confirmed by almost lifelong intimacy with good European society, were a shade too exclusive for the growingly democratic taste about him.” Park Street visitors interpreted his cold courteousness and the “metallic sharpness of his voice” as hostility. “His intellect was not open to new ideas,” Whipple added. “He excluded from his toleration what he had not included in his studies and experience; and he sometimes weighted heavily on the Boston mind during the period he was supposed to have undertaken its direction.” Even his nephew Charles Eliot Norton admitted that Ticknor suffered from “lack of imagination and lack of humor,” but much of his blunt plain talk came from worldliness. Hawthorne observed “something peculiar in his manner, and odd and humorsome in his voice; as one who knows his own advantages and eminent social position, and so superimposes a little oddity upon the manners of a gentleman.” Another friend William Dean Howells agreed. A man who whose “whole life had been passed in devotion to polite literature and in the society of the polite world” looked strange to a democratic age.[7]

Liberated from Harvard, Ticknor fled to Europe in 1835 and remained for three years, visiting old friends and familiar haunts. In late spring 1836, he arrived in Vienna armed with a letter of introduction from his friend the explorer Alexander von Humboldt to help facilitate a meeting with Metternich. The Bostonian and the Austrian crossed paths several times, but the busy Chancellor finally managed to carve out an hour for conversation on July 1.

Almost immediately, Metternich began to lecture the Bostonian on the dangers of liberalism and democracy. “Democracy is everywhere and always – partout et toujours – a dissolving, decomposing principle,” he announced. “It tends to separate men, it loosens society … Monarchy alone tends to bring men together, to unite them into compact and effective masses; to render them capable, by their combined efforts, of the highest degrees of culture and civilization.” Ticknor politely disagreed, defending American democracy as making strong independent men capable of self-government, “that men are more truly men, have wider views and a more active intelligence, where they do almost everything for themselves, than where, as in monarchies, almost everything is done for them.” Metternich conceded the point, but only slightly. Democracy works in America because it is habitual, but social and governing systems institutionalizing competitive individualism may progress economically but eventually splinter apart:

Democracy is natural to you; you have always been democrats, and democracy is, therefore, a reality – une verité – in America. In Europe it is a falsehood, and I hate all falsehood – En Europe c’est un mensonge. I have always, however, been of the opinion expressed by Tocqueville, that democracy, so far from being the oldest and simplest form of government, as has been so often said, is the latest invented form of all, and the most complicated. With you in America, it seems to be un tour de force perpétuel. You are, therefore, often in dangerous positions, and your system is one that wears out fast – qui s’use vite … I do not know where it will end, nor how it will end; but it cannot end in a quiet, ripe old age.

Democracy also suffered from a crippling internal problem: identifying and defeating evil. You can fight it in Austria, he told Ticknor, but in America you cannot until it is too late. “I labor chiefly, almost entirely, to prevent troubles, to prevent evil. In a democracy, you cannot do this. There you must begin by the evil, and endure it, till it has been felt and acknowledged, and then, perhaps, you can apply the remedy.” Metternich nevertheless spoke of America with affection, expressing his admiration for George Washington and the Federalist Party (“a sort of conservative party, and I should be conservative almost everywhere, certainly in England and America”) and admitted he almost moved to the United States as a young man seeking his fortune.[8]

Metternich’s chat clearly impacted Ticknor. When the 1848 revolutions came, forcing Metternich to flee, he wrote dejectedly: “The Revolution of 1830 gave political power to the middling classes; that of 1848 gives it to the working class. Are they capable of exercising it beneficially to themselves, or others? We think they are not. Will they attempt practically to exercise it? Not, we think, at first … But we look for little practical wisdom in the mass of the French, and fear that what there is will not be able to take the lead.” Republics will never last in Europe, which lacked the customs and history to sustain them.[9]

Ticknor did not need Viennese excursions to convince him on the wisdom of conservatism. He counted himself a conservative Federalist long after the party of Adams and Hamilton died and evinced a kind of Burkean prudence in politics. “His conversation showed his sense of responsibility which rests on every man of thought and integrity to transmit to others the great truths and traditions he has received as an inheritance from those before him,” his daughter wrote. “To discountenance opinions which he is satisfied are dangerous to civilization and to healthy progress (a duty, as he once wrote, especially important where government rests on public opinion); and to promote, so far as in him lies, the sovereignty of law and justice.” Americans were a practical people, not given to “metaphysical disease” or airy philosophical speculation divorced from life as actually lived. This allowed them to avoid the perpetual revolutions of France. “Since, therefore, our revolutionary condition has passed away – revolutionary, I mean, in intellectual movement as well as political – and has given place to a more settled state of things, we have shown little tendency to metaphysical discussions or controversies.” His model statesman, therefore, was Daniel Webster, that most Tory of American Whigs who placed a premium on maintenance of Union, the stability of private property, and the social responsibility of elites to improve their communities. When Webster died in 1852, Ticknor served as one of the “Godlike Daniel’s” literary executors.[10]

Ticknor exhibited that social responsibility in helping create the Boston Public Library, an effort he launched in the 1820s, and he believed education and literacy would make stable and productive citizens. “The principle that the property of the country is bound to educate all the children of the country, is as firmly settled in New England as any principle of the British Constitution is settled in your empire,” he wrote a British friend. Viewing it as a sister institution to Boston’s public schools, he insisted the new library be open to all classes and supply every range of literature, not just high-brow texts. “The library was to be – otherwise he refused to work on it – dedicated to serving the less favoured classes of the community, not the scholars, the men of science, and the like,” Green declared of Ticknor’s efforts. Anyone could have a library card, including children, and multiple copies of popular and literary books were purchased for the shelves. Ticknor himself bought titles to donate from American and European sellers and he eventually gifted his entire Spanish collection for the Library’s rare book room. By 1900, Boston Public Library was the second largest in the United States.[11]

As the country veered toward civil war in the 1850s, Ticknor’s conservatism came in for criticism. Abolitionists scorned him for not more stoutly opposing slavery and, although he regarded it as evil, opting for a gradual approach. The institution was too ingrained in Southern life, he asserted, and far beyond the reach of legislation to eradicate it. We would do better to wait for Southerners to understand its corruption and eliminate it themselves than to risk civil war by pressing for emancipation. “The great difficulty is, to make all interested in the matter willing to wait,” he frankly admitted. The war brought no joys, as the former social arbiter quickly became a pariah and rumors spread he risked arrest for criticisms of Lincoln and the war effort. Refusing to back down, he opposed creation of the Boston Union Club, calling it a “Jacobin Association,” supported General McClellan in the 1864 election, and called Lincoln a dictator “His mind was so oppressed by the technicalities of constitutional law, that he wished the war to be conducted on principles which would probably have insured the triumph of the rebels, had they been carried out,” Whipple noted critically. Howells remembered how two English visitors supped with him at Ticknor’s table postwar, relating a recent Southern trip and the miseries they witnessed. “When I ventured to say that now at least there could be a hope of better things, while the old order was only the perpetuation of despair, he mildly assented, with a gesture of the hand that waived the point, and a deeply sighed, ‘Perhaps, perhaps.’”[12]

In the years before his death in 1871, Ticknor turned gloomy and believed the United States was dying under the weight of “the unwholesome moral atmosphere of great cities,” massive standing armies, and jingoistic martial attitudes, all of which eventually lead to “violent revolutions which destroy all sense of law and duty, and at last overturn society.” The Civil War effectively killed the Old North he fondly remembered. When his nephew George Ticknor Curtis, the great constitutional lawyer and attorney for President Andrew Johnson, wrote a biography of Daniel Webster, he sent page proofs to Uncle George. Ticknor read them with a sense of mystification, since the world they described looked like a foreign country:

On reading the proofs I am more and more struck by the fact, that the events you relate, most of which have happened in my time, seem to me to have occurred much longer ago than they really did. The civil war of ’61 has made a great gulf between what happened before it in our century and what has happened since, or what is likely to happen thereafter. It does not seem to me as if I were living in the country in which I was born, or in which I received whatever I ever got of political education or principles.

Matters were little better overseas where Europeans bristled under their governments, a discontent with which he fully sympathized. As far as Ticknor could see, Metternich’s anxieties for the future had been fully realized.[13]

The importance of George Ticknor lies in contrasts, which bring into relief another America. As an old Federalist who worked to undergird volatile American democracy with traditions, Ticknor and his Brahmin compatriots “wove a tapestry of conviction and hope, doubt and despair, which became a conservative testament.” They built educational and cultural institutions, impressed upon citizens the importance of custom and law, and fostered a New England elite that guarded historically-grounded cultural tastes from metaphysical invaders. Ticknor’s primary goal was “to establish a decent society in which a man of letters could feel himself fully a citizen – both as democrat and aristocrat … The Gilded Age brought a sharp decline in the standards of that society, a cruel contraction in its idealism … But there was another, better Boston behind that, to be identified with Ticknor and the great institutions — the moralist, humanist, democrat, responsible Boston.” Ticknor’s impulse to preserve an orderly and decent society was a thoroughly Tory one and as Martin Green declared, the Autocrat of Park Street “simply, soberly, sensibly, was the American gentleman.”[14]

Notes:

[1] Life and Letters of George Ticknor, Eds. George Hillard and Anna Ticknor, Vol. II (London, 1876) 17; Martin Green, The Problem of Boston: Some Readings in Cultural History (New York, 1966) 183-84.

[2] Edwin P. Whipple, “George Ticknor,” International Review, Vol. III (1876), 453.

[3] Van Wyck Brooks, The Flowering of New England, 1815-1865 (Boston, 1936) 87-88; Green, Problem of Boston, 121-22; Barrett Wendell, A Literary History of America (New York, 1901) 265.

[4] Van Wyck Brooks, New England: Indian Summer, 1865-1915 (New York, 1940) 16; Green, Problem of Boston, 137; Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), 1 August 1871; Life and Letters of George Ticknor, Eds. George Hillard and Anne Ticknor (Boston, 1876) 390;

[5] Green, Problem of Boston, 183-84.

[6] Green, Problem of Boston, 80, 83-84, 184-86; David B. Tyack, George Ticknor and the Boston Brahmins (Cambridge, MA, 1967) 147-49, 151-53; Life and Letters, II, 235.

[7] Tyack, Ticknor, 155, 56, 160-61; Wendell, Literary History, 266; Whipple, “Ticknor,” 457; William Dean Howells, Literary Friends and Acquaintances (New York, 1911) 130-31.

[8] Life and Letters, II, 13-20.

[9] Life and Letters, II, 230-31.

[10] Life and Letters, II, 186, 193-94. Along with Ticknor, Edward Everett, Cornelius Felton, and George Ticknor Curtis also served as Webster’s literary executors.

[11] Life and Letters, II, 188; Green, Problem of Boston, 91-92

[12] Life and Letters, II, 221, 459; Tyack, Ticknor, 235-36; Whipple, “Ticknor,” 460; Howell, Literary Friends, 130-31.

[13] Life and Letters, II, 479, 485.

[14] Tyack, Ticknor, 194-96; Green, Problem of Boston, 99, 101.

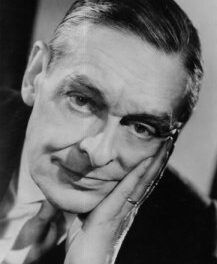

The featured image is “Engraved print of American academic George Ticknor with facsimile signature” (1867), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News