We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

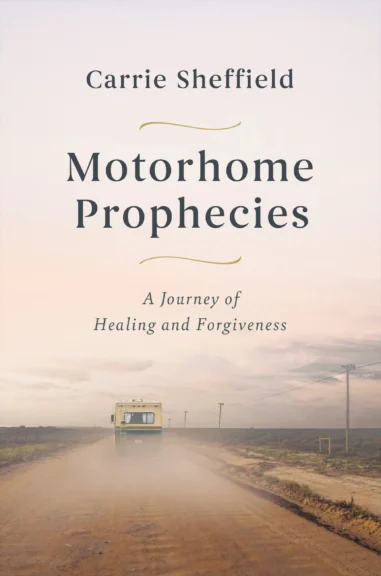

The Daily Wire caught up with policy analyst and author Carrie Sheffield to talk with her about her new book “Motorhome Prophecies: A Journey of Healing and Forgiveness,” (CenterStreet/Hachette Book Group).

DW: Let’s start with politics. You’ve served as a policy analyst and columnist for several years now, both in New York and in Washington. Which issues are paramount in your mind as we head into the 2024 presidential election season?

Sheffield: Certainly the economy and immigration are top of mind for many voters, including me. The fact that inflation has ravaged household wages is an ongoing and pervasive problem. The fact that average monthly mortgage payments under Biden have skyrocketed means real pain and the dream of home ownership moves out of reach for more American families. Seeing our border towns and cities like New York and Chicago overrun with sanitation issues and safety problems due to Biden’s failed immigration policies is discouraging and must be stopped.

DW: Speaking of presidents, in “Motorhome Prophecies” you write that your father was convinced he was a Mormon prophet destined to become president of the United States. Looking back, how did that influence the way your family lived?

Sheffield: Yes, my dad claimed that he’d be U.S. president one day. He also made some unproven claims, like President Reagan designating MLK Jr. Day because of my dad’s work supporting Dr. King’s messages and that his political essays influenced then-Speaker Newt Gingrich to impeach Bill Clinton.

Politics was in my dad’s blood because his father had been a successful Utah state lawmaker. He was also former chairman of the Salt Lake City Zoning and Planning Commission for 25 years. That his firstborn son would follow him into politics wasn’t too far-fetched.

My dad’s beliefs about his destiny absolutely motivated our nationwide travels in a street musical orchestra attracting listeners and then passing out patriotic and religious brochures. But the proselytizing came at an expensive price — his kids’ mental health and happiness. Multiple siblings have attempted suicide, two developed schizophrenia (it’s well documented that schizophrenia’s onset is exacerbated by childhood trauma), and I struggled with periodic suicidal ideation, depression, PTSD, and anxiety because of our dad’s zealotry.

Despite the negative aspects, dad gave me a deep love of our exceptional country, of intellectual inquiry, and beautiful music. Though we’ve had many disagreements, I know in his heart he has a deep desire to serve others through his work. I think his love of country in some ways blinded him to his personal life’s failures. That is a common fatal flaw for public servants. Children of politicians often experience abandonment problems as adults. Each generation must recognize and heal our own hurts.

CenterStreet/Hachette book Group

DW: “Motorhome Prophecies” is written in the vein of famous memoirs like “Hillbilly Elegy” by J.D. Vance, “The Glass Castle” by Jeanette Walls, and “Educated” by Tara Westover, all stories of young Americans growing up in very broken families. Yet each author is somehow able to escape and overcome their childhood trauma and find success as an adult. What were some factors that helped you overcome your childhood?

Sheffield: Necessity is the mother of invention. I knew that if I wanted a better life than the dark, dangerous one around me I needed to be resourceful, pragmatic and humble enough to ask for help. The bravest thing I’ve done took place when I was 18. In terms of the initial departure, here’s a passage from the book, it was actually my schizophrenic brother’s sexual assault and attempted rape that spurred me to start the process of leaving:

It would prove a long winding path, but Peter’s assault eventually became a catalyst for me to scrutinize my faith, to pray for God’s protection and guidance, and, eventually, to reject Ralph’s false prophecies and run away from home. I’m the fifth oldest sibling, but I was the first to escape the clutches of The Mission. That harrowing night back in 2000 taught me a lesson that would be reinforced time and again: life’s most wrenching crucibles can propel us to our greatest moments of growth and freedom.

I pushed myself to achieve in my career and work in public policy because I wanted a better life for myself than remaining trapped in a violent and impoverished environment. Also, as a woman, I wanted to bask in the freedoms denied my mother and myself as the first girl with four older brothers.

Early on, I also felt a sense of jaded insecurity that fueled my ambition. I wanted to prove my dad wrong. He prophesied that I’d be raped and murdered if I left the cult. I decided I’d soar to career heights surpassing his own. It’s a toxic, unstable motivation, to prove someone wrong, and it eventually comes crashing down.

Another reason I left was that I’d undertaken a long-term investigation into my dad and found his handwritten prophecies were in direct opposition to the teachings of the official LDS Church’s hierarchy.

For many years I struggled. I would paint myself in these absolutist black and white terms, that my dad was evil and that I was a hero for escaping. Today, though, I know I am not the hero of this book, but I am also not the villain. God is the hero, and though I thought my father was the villain, I now see he was crushed by severe religious zealotry sparked by mental illness after suffering sexual assault as a toddler. He also suffered through the death of his childhood best friend which led to enduring isolation. He’s just as deserving of God’s mercy and compassion as I am. I love my father and am sorry I waited so long to forgive him. I believe forgiving him earlier would have stopped me from some toxic self-sabotaging that I did to cope with the trauma.

Credit: Carrie Sheffield.

DW: Your book deals a lot with mental illness. Authors like Abigail Shrier and Jonathan Haidt have also written books this year on young people struggling with mental illness. It seems to be a growing problem. Why do you think it’s a common thread and what are the broader takeaways found in “Motorhome Prophecies”?

Sheffield: Certainly depression and suicide are rising, and this is troubling. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention late last year released provisional data showing nearly 50,000 people committed suicide in the United States in 2022. This nearly 3% increase from 2021 is the highest number ever recorded and the highest rate since 1941 — the aftershocks of the Great Depression. It’s nearly 17 times the number of people killed in the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Gen Z is far more secular than their parents were when they were young, and I think it’s no coincidence Gen Z is also suffering far greater isolation and mental illness. This is a trend we can and must reverse. People who attend religious services at least weekly are significantly less likely to die “deaths of despair”— suicide, drug overdose, or alcohol poisoning, according to 2020 research from Harvard University’s School of Public Health. A literature review appearing in Psychiatric Times reported: “Of 93 observational studies, two-thirds found lower rates of depressive disorder with fewer depressive symptoms in persons who were more religious. … a review of 134 studies that examined the relationships between religious involvement and substance abuse [concluded that] 90% found less substance abuse among the more religious.”

Ironically, research from the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality found atheism correlates with emotional suppression. Psychology professors (along with biologists) are least likely among all disciplines to believe in God, Harvard reported. The journal Sociology of Religion similarly found that psychologists are the least religious of American professors. This is a troubling combination. The same trained experts ordained to heal mental disorders are sometimes the very ones who are skeptical of rescuing balm.

A recovered agnostic, I experienced the power of faith to heal my own mental health, as I recount in my book. The biggest hurdle I needed to overcome was comprehending the difference between man-made abuse and healthy faith in God.

DW: Eventually you went to college and ended up at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. How did your worldview change while in Cambridge?

Sheffield: I became more aware of the narratives around “privilege” being crafted at places like Harvard. I gained a sense of understanding perhaps their altruistic impulse — indeed, our country had sexism, slavery, and Jim Crow as stains in our history. But eventually, I came to realize that good intentions do not equal good outcomes.

At Harvard, I also became more entrenched as an agnostic, which is sad because Harvard was founded to help clergy grow their intellectual capacity to teach the mind of God. Around 7 years after I graduated, during my Christian conversion process, the more I studied science, including metaphysics, history, anthropology, and other disciplines, the more my faith in God and my confidence in Christianity grew. Studying Christianity felt like uncovering buried treasure discarded by intellectuals at places like Harvard who had discounted its scientific and philosophical heft.

DW: You’ve written many articles over the years for various periodicals, but this is your first time writing a full-length book. What was the process like for you?

Sheffield: Writing a 90,000 word book is indeed a far heavier lift than a news article. I tell people who ask advice for writing a memoir to begin a journal today if they don’t already. This memoir genre was made far easier for me because I’ve got a stack of journals to assist. I’ve kept a journal since age 8 because journaling is strongly encouraged in the LDS Church and Mormon diaspora community due to strong cultural appreciation of genealogy and family history — the LDS Church has more than 2 billion records in its genealogy database. Also, as a newer faith, we know many things about its early origins due to contemporaneous journals. As a journalist, the personal journals made the process far easier for accuracy — I didn’t have to make up what I was thinking, I knew directly.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News