We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

The mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection lends itself to, perhaps even demands, pictorial realization like no other story. To prove that the Easter spirit hasn’t left the silver screen, here are two more recent entries you may have missed.

Movie-watching may not be as common a pastime at Easter as on other holidays, but the Easter movie is a true genre—and an important one. The mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection lends itself to, perhaps even demands, pictorial realization like no other story. This was shown preeminently during the heyday of biblical epics like Ben-Hur or The Greatest Story Ever Told, films in which Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection are either background or central theme. But to prove that the Easter spirit hasn’t left the silver screen, here are two more recent entries you may have missed (and which have some curious connections). They are both far too good to be forgotten in the cultural whirlwind.

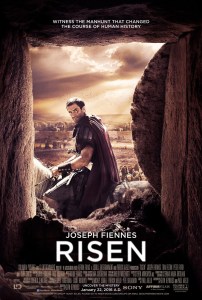

If you saw Risen (2016) upon its release, you’ll remember its tag line: “Witness the Manhunt that Changed the Course of Human History.” Like earlier prototypes Ben-Hur and The Robe, Risen is a fictional story woven around Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. It stars Joseph Fiennes as a Roman tribune who, after assisting at the Crucifixion, is tasked by Pontius Pilate with investigating the mystery of how Jesus’ body disappeared from the tomb and quelling any uprising that may result.

If you saw Risen (2016) upon its release, you’ll remember its tag line: “Witness the Manhunt that Changed the Course of Human History.” Like earlier prototypes Ben-Hur and The Robe, Risen is a fictional story woven around Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. It stars Joseph Fiennes as a Roman tribune who, after assisting at the Crucifixion, is tasked by Pontius Pilate with investigating the mystery of how Jesus’ body disappeared from the tomb and quelling any uprising that may result.

Clavius, the tribune, is a man for whom brutality in the defense of the Roman Empire is all in a day’s work. At the start of the film we see him violently putting down a Zealot revolt led by Barabbas. In the subsequent scenes between Clavius and Pilate, who has just ordered Jesus’ crucifixion, we see a picture of pagan Rome in spiritual decay—as much in need of the coming Messiah as the Jews are. We see Clavius repeatedly and futilely washing himself, attempting to cleanse away the blood and gore of his exploits. The images of water recall baptism, the only thing which will make Clavius truly clean. As Pilate and Clavius wash themselves in the Roman baths, they discuss Clavius’ career and his desire for “an end to travail; a day without death; peace.” Pilate wonders aloud if there is not “another way” to achieve these things than through the cruel assertion of power.

Visual symbols are used tellingly throughout the film. Hourglasses reflect the fleeting nature of time, and the evergreen plant that Clavius rubs his fingers against to destroy the smell of blood is just one of the many motifs (like water and white clothes) that signal eternal life and the advent of the Christian faith. As Clavius inches ever closer toward conversion—hindered at times by a sycophantic second-in-command named Lucius—he becomes an everyman, a symbol of all of us as we grope our way toward God.

But Clavius assisted at Jesus’ crucifixion, ordering his side to be pierced to speed his death. Although at first acting as a mere minion of Pilate, Clavius finds himself drawn into question Jesus’ identity and curious as to whether this figure can give him the spiritual sustenance that his own culture is no longer able to provide.

As he interviews Mary Magdalene, the apostle Bartholomew, and the soldiers who guarded Jesus’ tomb on the night before the Resurrection, Clavius feels his defenses cracking and himself wondering whether this incredible mystery could possibly be true.

The search culminates in the astonishing moment when Clavius discovers Jesus—very much alive—in a cave with his disciples. Clavius continues to follow from afar, finally encountering Jesus face to face on a rocky cliff overlooking the sea. Viewers may differ as to whether the film fulfills expectations in portraying the world-shattering personality of Christ; but Risen is not meant as a treatise on Christology. It is instead a conversion story couched as “the greatest detective story ever told,” and in that it succeeds.

Through the intelligent writing, we get a world-historical view of the story of Jesus; we see not only the coming of one man to faith in Christ, but anticipate the rebirth of an entire civilization. One of my favorite moments in this vein comes toward the end. Clavius has gone off to follow the risen Jesus and his apostles, and Pilate has sent a search party to bring him back. When they turn up empty-handed, Pilate turns toward the sea and declares with sublime inaccuracy, “I doubt we’ll ever hear from them again.”

And who is to say that a Clavius couldn’t have existed? According to the Gospels, one Roman centurion professed faith in Jesus’ healing powers, another declared his divinity at the foot of the cross. Perhaps one or both of these men took Clavius’ path toward Christ. After all, “there were also many other things which Jesus did” which would fill endless books (and screenplays).

* * *

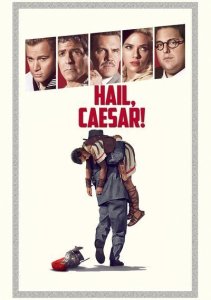

You could watch Hail, Caesar! (2016) all the way through without realizing it’s a religious film, so skillfully have its creators, the famed duo of Joel and Ethan Coen, infused spiritual themes into this delightful frolic through the Golden Age of Hollywood.

You could watch Hail, Caesar! (2016) all the way through without realizing it’s a religious film, so skillfully have its creators, the famed duo of Joel and Ethan Coen, infused spiritual themes into this delightful frolic through the Golden Age of Hollywood.

The central figure of the movie is Eddie Mannix, the production head at a Hollywood movie studio in 1951. In the course of a day, Eddie goes about shepherding his wayward flock of movie stars, protecting their messy private lives from the tabloids. We see hilarious snatches of the movies in production, ranging from horse operas to song-and-dance shows to an aquatic ballet. But the studio’s “prestige picture” is Hail, Caesar!: A Tale of the Christ, an epic about a Roman centurion who comes to believe in Jesus. (The character, played by George Clooney, is reminiscent of Joseph Fiennes’ tribune in Risen. What’s even funnier, Joseph Fiennes’ brother Ralph has a role in Hail, Caesar! as a fussy English director.)

Disaster strikes when the star of the production, Baird Whitlock, is kidnapped by a group of disgruntled Communist writers calling themselves The Future, and held for ransom. Unless Eddie can rescue Baird, the film and the studio are in peril.

Meanwhile, Eddie faces a severe temptation when an executive from the Lockheed Corporation tries to recruit him for a job. It would promise better hours and pay and more serious work—namely, the building of atomic bombs. The Lockheed man scoffs at Eddie’s movie work as frivolous “make-believe”; “the future,” for him, belongs to progress and profit.

Now, it so happens that Eddie is a conscientious Catholic, given to late-night visits to the confessional (two of which frame the film) and concerned about following the will of God in his life. After spending a reflective moment on the movie set for the crucifixion, he realizes that he is already doing what he was called to do, and he returns to his vocation with a renewed sense of purpose.

All this time Baird has been on a spiritual journey of his own. After being rescued from the gang of Soviet sympathizers—whose scenes are brilliantly satirical—he shows up at Eddie’s office spouting Marxist doctrine. The movie studio is nothing but an arm of capitalism, he says; movies have no artistic value or spiritual dimension but are merely “bread and circuses” for the masses.

Eddie responds by slapping Baird silly and telling him to complete Hail, Caesar!: A Tale of the Christ like a true star. Baird proceeds to deliver his climactic speech at the foot of the cross, a speech about his life-changing encounter with Jesus, but forgets the key last word—“faith.”

Hail, Caesar! is a movie of hidden depths that rise to the surface with each viewing. So many elements of the film—even its original release date, at the start of Lent—chime in with the themes of the Passion and Resurrection. Eddie is traveling a Lenten journey through the desert of Hollywood, trying to kick his smoking habit while fighting off temptations from a modern-day demon in a business suit.

The film’s poster puts the spiritual meaning in plain view: Eddie carries Baird on his shoulders like Christ carrying his cross, with Baird’s Roman helmet lying overturned on the ground. By suffering for his flock, shouldering their failings, and protecting them from harm, Eddie enables them to produce something of value, a work of art that will instruct, enlighten, and entertain, something greater than their frivolous individual lives. Because, as Eddie explains, the common people rely on “pictures” as an embodiment or realization of the Word of God.

Combining lightness and profundity, the Coen brothers play upon such varied themes as the golden era of Hollywood biblical epics, the metaphysical struggle between Christianity and Communism, and the moral consensus of mid-century America—shown especially in the hilarious scene in which a rabbi and three Christian clergymen argue about the nature of Jesus and the Trinity. The Coens’ command of setting, dialogue, and history is dazzling, and the way they weave serious topics into their zany plot charms and beguiles.

With blindingly beautiful imagery, Hail, Caesar! conveys the idea of grace working in the midst of a crazy, imperfect world—a world in which we all have a God-given role to play. It is, in its odd way, one of the most profound movies I have ever seen, and a godsend for the Easter season.

This essay was first published here in April 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a still from Risen (2016), courtesy of IMDb.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News