We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

“Good Friday is not just one day of the year,” Fr. Richard John Neuhaus writes in “Death on a Friday Afternoon. “ “It is a day relived in every day of the world, and of our lives in the world.”

There is “no denying that the cross is surrounded by glory,” wrote Fr. Richard John Neuhaus in Death on a Friday Afternoon, his meditations on the Seven Last Words of Christ, those mysterious and sometimes puzzling statements the Gospels record him saying from the Cross. As Fr. Neuhaus continued, the Cross is itself of a mysterious and puzzling nature. “It is, at the same time, the sign of utter defeat and indomitable hope. The defeat and the hope must ever be held together; the hope is not hopeful unless it has taken into account everything that contradicts hope.”

This taste for and ability to draw out the paradoxical quality of Christian belief marked out Lutheran minister cum Catholic priest Neuhaus as a kind of successor to Chesterton. A man who was comfortable wrestling with public policy and the world of politics, Fr. Neuhaus always made it clear that such things were “second things.” The journal he founded, edited, and wrote (about a third of each issue was made up of his words in the back of the magazine and often in the middle, too) was titled First Things to signal that its emphasis would be not on the political horse races, the details of the bills and regulations, or the (increasingly smokeless) back rooms where the deals were made. Instead, it would be dedicated to literary, historical, philosophical, and theological realities.

This year marks the fifteenth since his passage from this life. I’ve often wondered what he would make of the increasingly strange times we live in. I suspect he would not be terribly surprised. Though he liked to say that “America is, as it always has been, an incorrigibly, confusedly, and conflictedly Christian society,” his last book was titled American Babylon. A man very aware of the movement of his own time, he certainly saw the difficulties coming, but he emphasized in that volume that he was calling America Babylon “not by comparison with other societies but by comparison with that radically new order sought by all who know love’s grief in refusing to settle for a community of less than truth and justice uncompromised.” No matter how bad or good things are at a given moment, the glory that attends this country and, indeed,this whole world will always be mixed up with that “utter defeat.”

This is why those meditations in the earlier book, Death on a Friday Afternoon (2000), are so powerful. They refuse to take away the paradoxical character of Christian faith. Like all of Fr. Neuhaus’s writings, they may well include things we might think wrong, but, if so, it is because they deal with those first things that are the highest things. As I read this book for the first time this Lent, I reflected that if his reach sometimes exceeded his grasp, that is itself meritorious. Like St. Paul, he is writing about Christ crucified, a situation St. Paul called “a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles” and yet is “the power of God and the wisdom of God.” The message throughout Fr. Neuhaus’s volume is not to hurry our way through Good Friday on to Easter as if it were “simply the dismal but necessary prelude to the joy of Easter” but see it instead as “the drama of the love by which our every day is sustained.”

We Christians are an Easter people, as St. Augustine liked to say. “Alleluia” is indeed our song. But that loving praise to God will always be, in this life, faithful and hopeful. Faith is the assurance of what is not seen, while hope is the desire for what faith promises. If we are an Easter people, we are also a Good Friday people, one for whom the power of Christ’s Resurrection is giving us the ability to follow behind him, take up our own crosses, and imitate him. “Christ plays in ten thousand places,” Gerard Manley Hopkins tells us. Our own lives become a theater in which that divine drama, played out when Pontius Pilate was governor, becomes present to the world in every age thereafter.

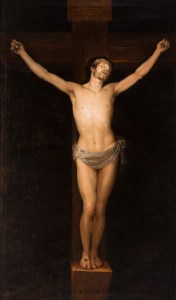

“Good Friday is not just one day of the year,” Fr. Neuhaus tells us. “It is a day relived in every day of the world, and of our lives in the world.” Some Christians object to the crucifix, the image of Christ on the Cross, because Christ is risen. But that image is so central not only because it reminds us of what redemption cost the Son of God made Man; it is central because it reminds us of the price that the free grace of redemption costs us. For to accept the free gift of eternal life means to be made like Christ—people who will follow the Father’s will wherever it leads, even death on a cross. “The truth is that Good Friday forms the spiritual architecture of Christian existence,” Fr. Neuhaus tells us. “It is by this world, this world at the cross, that reality is judged.”

This world tells us that our sins are nothing, really. They don’t matter. Yet the one who dies, asking forgiveness for those who “know not what they do,” shows us that our sins do matter because we matter. “Spare me the sentimental love,” Fr. Neuhaus says, “that tells me what I do and what I am does not matter.” Our sins have separated us, “sundered” us, from the source of life and love. The Cross tells us that God thought that distance from us was worth something, that he wanted us to be “at one” with himself.

In what does that atonement consist? Fr. Neuhaus doesn’t claim to explain how it happened. But he spends some time looking at modern theories that have been proposed. Liberal versions that wish to get rid of the notion that Jesus is a sacrifice have simply offered us something that is not Christianity. Paul Tillich’s notion that the “Christ event” simply communicated the message that we are all “accepted” by God is, says Fr. Neuhaus, “finally another form of positive thinking.” On the other hand, versions of a “substitutionary atonement” often speak as if Christ’s sacrifice is something “God did to Jesus.” A much better way to think about this is to think of Christ not simply as our “substitute” but our “representative” and remember that the Trinity is not simply a collective working together but the one God whose love is from first to last.

The entire plan is love from beginning to end, and the fullness of God—Father, Son and Spirit conspiring together to save us from ourselves. At the Father’s command, the Son freely goes forth in the power of the Spirit to become one of us. On our behalf, as Representative Humanity, he lives the life of perfect obedience that Adam—and all of us “in Adam”—failed to live. And he completes that life by dying the perfect death.

The sacrifice of Christ is completed on the Cross, but it is not limited to it. Christ’s perfect obedience was from his first human moment until eternity. Every moment of his existence was an offering to his Father. Yet there is on the Cross a kind of summing up of that sacrifice in those hours and those few sentences of his.

The sacrifice of Christ is completed on the Cross, but it is not limited to it. Christ’s perfect obedience was from his first human moment until eternity. Every moment of his existence was an offering to his Father. Yet there is on the Cross a kind of summing up of that sacrifice in those hours and those few sentences of his.

In the place where even God seemed hopeless, we find the grounds of our hope: forgiveness for those who know not what they do, his promise of paradise for a thief, his giving of Mary and John to each other, his cry of dereliction, his thirst, his declaration of completion, and his commendation of his Spirit to his Father.

The story of Jesus, especially the part about the Cross, is the strangest story of all time, yet, “[t]hat it embraces every strangeness is testimony to its truth.” Unlike some books of “meditations,” Fr. Neuhaus’s stretches 260 pages. Even at that, he admits, there are countless avenues that could have been explored. His book is an “exploration into mystery,” by which he means not “a puzzle, as in a murder mystery” but “an adventure into wonder, with each wonder that we encounter leading on to the next and greater wonder.” That is as it should be.

I recommend Fr. Neuhaus’s book for next Good Friday. Or, frankly, any time. For the Cross involves all time. But Christians don’t even need that book to reflect. Even to read today the passages in which those immortal words spoken by one experiencing mortality is to enter into that mystery, to hear again words of life uttered in the face of death, and know that they must somehow become the words of any who call themselves Christian and take up their own crosses. Christ’s Cross is indeed empty, but he wishes us to take it up ourselves. Paradoxically, this sacrifice of the self is the only way to gain our own identities. As Fr. Neuhaus puts it, “the only definition of the self to be trusted is the self that is on the far side of being crucified.”

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is Cristo crucificado en la agonía (1804), by Felipe Abás Aranda after Francisco Goya, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News