We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

One common criticism of realism is that it is merely mimicking what can now be done as well or better with a camera. This is simply not the case. With few exceptions, photographs only show the surface, not the personhood of the subject.

During the time that I was Director of the Center for Faith and Culture at Aquinas College in Nashville, Tennessee, I was blessed to form a friendship with the composer Michael Kurek and the artist Igor Babailov. Both these men are masters of their respective disciplines and both have shown great courage in opposing the fads and fashions of modernism.

Igor Babailov’s aesthetic creed is expressed in his painting, The Resurrection of Realism, in which a cherubic youth is shown bursting through the fragmented ruins of Picasso’s Guernica. “The idea for this work came to me as a response to the growing hunger for Beauty in contemporary visual arts,” Mr. Babailov explains. The painting shows the innocent angelic looking child, symbolizing Realism, bursting forth in a blaze of beauty.

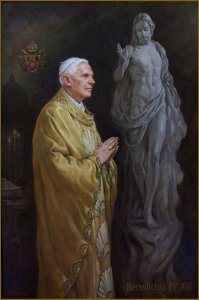

Igor Babailov practices what he preaches, his own works of realism bursting forth, ablaze with beauty, amidst the darkness of modernism and postmodernism. He reminds me of his great twentieth century forebear, Pietro Annigoni, whose realism outraged the abstract expressionist ascendancy. Annigoni and six other realist painters caused great controversy with their signing of the manifesto of Modern Realist Painters in 1947 which voiced their opposition to abstract art and other expressions of artistic formlessness. Something else that unites Babailov with Annigoni and, for that matter, with Sir James Gunn, another realist master, is their celebrated portraits of famous people. Annigoni and Gunn were both commissioned to paint portraits of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and the Royal Family. Similarly, Babailov has been commissioned to paint the three most recent popes, his painting of the saintly Benedict XVI being a particular favourite of mine.

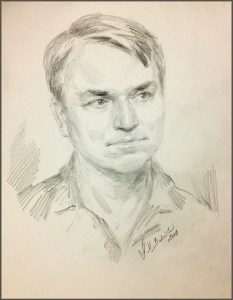

One common criticism of realism is that it is merely mimicking what can now be done as well or better with a camera. This is simply not the case. With few exceptions, photographs only show the surface, not the personhood of the subject. What photograph can show the enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa, a smile which is not only on the lips but in the eyes? What photograph of Benedict XVI captures the spirit and sanctity of the man as well as Igor Babailov’s portrait? Similarly, the two pencil portraits he did of me seem to be much more alive than any photographs. They are perhaps flattering, suggesting the use of artistic license in the good-natured omission of blemishes or signs of aging, but they nonetheless capture something that the camera does not and cannot. This je ne sais quoi is the mystique of the Muse, the mystery of genius.

Since we are discussing realism in association with this mystique which transcends the merely mechanical mimicking of the reproductive power of the camera, it would be good to look a little more deeply at realism itself. If realist art aims to capture the spiritual, as well as the physical qualities of its subjects, we need to see realism in its philosophical fullness. Technically speaking, in terms of philosophy, realism is the belief that universals and transcendentals, such as goodness, truth and beauty, have “real” existence, as distinct from the opposing view of nominalism which denies the reality of universals and transcendentals, seeing them as mere names. There is, therefore, a distinction that needs to be made between the metaphysical realism of philosophers, such as Aristotle and Aquinas, and the radically different “realism” of philosophical materialists who deny the existence of metaphysical reality.

In this sense, and perhaps controversially, I see the German artist, Albrecht Behmel, as a realist painter. His work explores the mystical and philosophical connection between physics and metaphysics and the creative space it presents to the artist and to the viewer engaging with the artist’s work. In my interview with Mr. Behmel in the current issue of the St. Austin Review, he explained the inspiration for a series of paintings about God’s creation of the cosmos. Let there be light I and Let there be light II are about the first moments of creation. What could this have looked like? “It is almost impossible to imagine,” says Behmel, “so I went back to geometry.” Beginning in the first painting with the simplest primal shape, the circle, this is developed in the second painting with a multiplicity of triangles. “Circles, half-circles and triangles are the building blocks of nature and human constructions,” Behmel explains; “there is no architecture without them and I mean this both literally and symbolically.”

Although Albrecht Behmel’s paintings might seem to resemble modern abstract art, such a resemblance is merely superficial. Whereas abstract expressionism pursues formlessness as an expression of philosophical nihilism, “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”, Behmel’s art is all about finding form in the midst of apparent abstraction. It is the very opposite of abstract expressionism and indeed of the impressionism which preceded expressionism.

Compare, for instance, Behmel’s painting, The Speed of Light, with a painting on a similar theme, Rain, Steam and Speed by the proto-impressionist painter, J. M. W. Turner. In both paintings a train is shown to be speeding towards the viewer. In Turner’s painting, definition is spurned in deference to a blurring of form into mere colour. This spurning of definition and the definite was seen by Chesterton as a sign of philosophical relativism, prompting him to say that “Impressionism … is another name for that final scepticism which can find no floor to the universe”. In Behmel’s painting, the train can only be found if we seek its definition and find its form. Furthermore, as we study the painting, we discover other figures and forms. In Behmel’s words, it is a landscape “populated with some of the most iconic visualisations in physics”, including Schrödinger’s cat and a Möbius strip. We can also discover Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, which Behmel describes as “one of the most influential fusions of mathematics and art in the history of ideas”. Placed at the top of the painting, Behmel states that Leonardo’s perfectly formed man is “positioned like a medieval patron saint in the top middle of the painting”. We might also be tempted to see the Vitruvian Man’s outstretched arms as symbolic of Christ, arms outstretched either on the cross or in triumph following His Resurrection. Also to be discovered are the heads of Lise Meitner, the Austrian-Swedish physicist, and Albert Einstein, who is depicted laughing.

The figure of the laughing Einstein is itself a symbol of the spirit of Behmel’s work. Unlike the dreary and prideful abstract expressionists who fall, like Satan, by the force of their own gravity, taking themselves far too seriously, Behmel’s art exhibits the sort of humour, which is the fruit of humility. “Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly,” wrote Chesterton. If this is so, we can see something almost angelic in Behmel’s work. As for the train itself, it really is travelling towards us at the speed of light because this is the speed with which it reaches us when we see it.

Considering this philosophical underpinning to Behmel’s work, I asked him if his art points beyond the dis-integration of abstract expressionism towards a reintegration in Christian realism.

“Oh yes,” he replied, “absolutely!”

Behmel paints puzzles not merely because life is puzzling, though of course it is, but because meditating upon the puzzle offers answers, not merely questions. His art contemplates the indissoluble marriage of faith and reason, while respecting the need to integrate reason with mystery. It responds to Macbeth’s despairing cry, and the despairing scream of abstract expressionism, that life is “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing” with Hamlet’s admonishment that “there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in [their] philosophy”.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News