We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

If orthodox believers in churches and schools do not take upon themselves the responsibility of passing down the deposit of Christian art that has been entrusted to us, the next generation will grow up with little to no knowledge of, or gratitude for, the images by which the Christian worldview captivated the heart, soul, and mind of the West.

A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity, by Mary Elizabeth Podles (222 pages, St. James Press, 2023)

I have had the privilege for the last several years of teaching, each spring, a class on the Bible in art for our MFA students. Although I, being a good American, cannot help but applaud the Impressionists, as I do the Romantic poets, for democratizing the subject matter of art, I regret that their success helped bring an end to the heyday of Christian painting, sculpture, and architecture. Many artists, it is true, continue to borrow visual and thematic elements from Christianity; however, the time has long past since western artists turned instinctively to the Bible for their major source of inspiration.

Thankfully, this aesthetic turn away from the Bible has not robbed us of the rich legacy of medieval, renaissance, baroque rococo, and neoclassical Christian art that continues to awe and arouse, illuminate and challenge those who visit museums and cathedrals across the world. The secularization of the West has yet to succeed in expunging that legacy, but that may very soon change. Yale’s 2020 decision to eliminate—that is to say, cancel—its popular art history survey course sounded an alarm that our secular universities stand on the brink of abdicating their duty to preserve our Judeo-Christian artistic heritage.

Let me put this as plainly as I can: if orthodox believers in churches and schools do not take upon themselves the responsibility of passing down the deposit of Christian art that has been entrusted to us, the next generation will grow up with little to no knowledge of, or gratitude for, the images by which the Christian worldview captivated the heart, soul, and mind of the West. One way of fulfilling that aesthetic commission is to write and disseminate books like A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity.

In this beautifully-printed book, Mary Elizabeth Podles, who holds an MA and MPhil from Columbia, is Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and teaches Sacred Art and Architecture at St. Mary’s Seminary & University, takes us on an intellectual, emotional, and spiritual journey through some of the greatest Christian art ever conceived. Living as we do in a society where the image of God in art and in man has been increasingly corrupted, Christians who care about the arts would do well to feed on the artwork in this book and learn to perceive anew the true imago Dei.

A Thousand Words began its life as a series of columns in Touchstone, a journal of mere Christianity whose conservative Catholic, Orthodox, and Evangelical editors and writers are committed to defending and propagating traditional Christian theology, history, philosophy, literature, sociology, science, and art. In keeping with the adage, “a picture’s worth a thousand words,” each column devotes a thousand words, not only to unpacking the symbolism and deciphering the allusions of a single work of Christian art, but to inviting its readers into the mystery of creation itself. Although each chapter of the book can stand on its own, Podles, by arranging the chapters chronologically, provides her readers with a firm grasp of art history, focusing on how different ages, movements, and countries have incarnated the gospel message in a wide range of media. By interlacing her chapters with a series of previously-unpublished, one-page overviews of each major period, Podles gives further unity and focus to her book.

To increase that unity and focus she returns often to key themes that serve as aesthetic leitmotifs. The most important of these themes explodes a misconception held by many conservative Christians: that the history of art is one long movement away from realism toward abstraction. In fact, Podles explains, the history of art has been marked by an ongoing pendulum swing between naturalism—which she defines as “the portrayal of things as they appear in nature”—and abstraction—which, she explains, “draws out, or abstracts, the essential form and not the superficial appearance” (13-14).

Podles highlights one of these swings by zeroing in on the monumental statue Emperor Constantine had made of himself, but then altered to fit his conversion to Christianity. In its original version, the head of the statue embodied the realistic style of the Roman Empire, complete with “bulging veins” and “battered toes.” In later versions, the face was thinned out and the eyes “enlarged and turned in a slightly upward direction” to render Constantine’s expression “transcendent, gazing heavenward upon the Eternal” (14).

This change, Podles argues, “begins a new swing toward the abstract in art, prompted by the Christian concept that everything in the natural world reflects or is a sign of, the supernatural world beyond. The new art of the Byzantine Empire moved away from naturalistic representations of the world toward a flattened and dematerialized mystical imagery” (14). In several excellent chapters, Podles shows how icons, which continue to define the sacred art of Eastern Orthodoxy even as they exerted influence off and on in the Western Catholic church, draw the worshipper closer to God by means of abstraction.

As “holy and venerable objects,” icons in the East “were understood as real windows onto the supernatural world. They revealed in tangible form what was truly unseeable except to the prayerful inner eye. The Resurrection, for example, was shown not as a physical event, but in its salvific symbolic meaning…. In fact, every icon is an embodiment of the supernatural reality of Christ’s breaking through and manifesting himself” (53). That is a strong claim, but Podles backs it up by presenting us with sacred art that beckons us past the limits of our physical world, even as it breaks down the barrier between time and eternity, space and infinity.

One way that icons open the window on to heaven is by using gold to capture the divine, uncreated light of God that broke through at the nativity, baptism, transfiguration, and resurrection of Christ and when the three angels, as a theophany of the Trinity, visited Abraham (see Genesis 18). But icons are not the only vehicle for earthly/heavenly trafficking. In Northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, artists like Jan van Eyck used the new medium of oil painting to unite the resurgent naturalism of the Italian Renaissance with the abstraction of the East.

“Now it was the everyday objects of ordinary life, meticulously rendered, that assumed a symbolic weight, disguised under visible form. Every object was imbued with meaning, sanctified as a metaphor for a supernatural equivalent in down-to-earth disguise. Thus was coined a new language, one that we in the modern world have perhaps lost the ability to read” (69). Podles unlocks that symbolic language, not so we can impress our friends at a cocktail party or win at Trivial Pursuit, but so we can learn to see anew the presence of God in every tree and stone and blade of grass.

Meanwhile, in Italy, where Renaissance naturalism rivaled that of classical pagan Greece and Rome, the Byzantine window onto heaven became more realistic without losing its spiritual power. Light, for example, “is now rendered naturalistically, but with an understanding still of its supernatural connotations, a continuing consciousness of Eastern Christianity ‘s concept of divine light” (91). Once again, man became the measure of all things; now, however, man’s “proportions were seen to reflect the harmonies of the divine, and, in Leonardo’s hands, the human figure began to be the perfect expression of the fullness of the human drama of theology” (95).

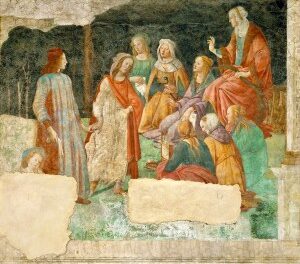

In the art of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian, Podles helps us discern the full freight of spiritual meaning that shimmers in every detail and gesture. She is at her best in opening up Raphael’s twin celebrations of theology (The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament) and philosophy (The School of Athens). In the former, she conducts us through “the largest complex of figures in fresco ever created, a Cecil B. DeMille crowd carefully managed and grouped in rhythms and accords that make a rational and coherent, readable whole” (105). Separated by a bank of clouds, the top and bottom portions of the fresco draw us into the heavenly and earthly realms of the church. Meanwhile, left and right contrast the power, and ministry, of the active-practical-pastoral life with that of the contemplative-intellectual-doctrinal life.

The fresco abounds with feverish energy, and yet, “there is no lack of focus. All the perspective lines, all the diversity of figures, converge toward the monstrance at the vanishing point of the picture. The Eucharist is at the heart of the earthly realm and is the breaking through of the Godhead into the ordinary world” (107). As The Disputation holds in tension the contemplative and active life, so The School of Athens establishes an equilibrium between natural and moral philosophy: “the poetical and heavenly strain of Platonic discourse is balanced by the lucid clarity of Aristotelian investigation” (111). Again and again, Podles trains the eyes of her readers to look at a work of religious art and identify the dividing line in the canvas or fresco that separates, even as it unites, the earthly and heavenly realms.

That uniting and dividing is particularly strong in El Greco, who studied in the naturalistic, high Renaissance studio of Titian but then, true to the aesthetic pendulum swing that Podles never lets us forget, fused it with the more mystical abstraction he learned as a painter (or “writer”) of icons on the Greek island of Crete. Indeed, in one of her most revelatory chapters, Podles demonstrates how El Greco helped fashion a new iconographic language for representing Joseph, the husband of Mary and stepfather of Jesus. No longer the little old man seen sleeping by the manger in early eastern and western depictions of the nativity, Joseph becomes an embodiment of strong and masculine, yet warm and tender fatherhood.

Why the change? Because, Podles explains, a new vision of Joseph was needed to help repair the sorry state into which marriage had fallen in the late Middle Ages. “Divorce, or rather annulment on complicated grounds of consanguinity, was rife. Families fell apart. The resulting chaos, and the general reluctance to institute drastic reforms, was one of the generally unacknowledged causes of the fracture we call the Reformation” (138). To heal the wounds, the Counter-Reformation sparked by the Catholic Council of Trent looked to artists like El Greco to provide the needed vision of a more robust Holy Family.

What I have written above only scratches the surface of the rich insights that greet the reader of A Thousand Words. Given its origin as a series of free-standing columns, the book necessarily leaves out such artistic movers and shakers as Duccio, Masaccio, and Botticelli, Bosch, Cranach, and Grunewald, Tintoretto, Rubens, and Tiepolo. Still, after stepping back to give a fair assessment, I concluded that there were only three major Christian artists whose presence left something of a gaping hole in the story that Podles tells: the late medieval Giotto and early Renaissance Fra Angelico, who helped define the way we visualize the events of the gospels, and the baroque Caravaggio, who taught us to see again such key biblical scenes as the beheading of Goliath, the calling of Matthew, the healing of Thomas’s doubts, and the surprise of the travelers on the Road to Emmaus.

Fortunately, that loss is made up for by splendid gains: a fascinating look at pre-1066 English religious artifacts; a three-part tour of the Ghent Altarpiece; an analysis of the Risen Christ, Michelangelo’s least known and least appreciated statue; investigative readings of Vermeer’s A Woman Holding a Balance and Benjamin West’s Nativity; close readings of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Annunciation and Flight into Egypt; a two-part celebration of Matisse’s modern, deceptively-simple designs for the Chapel of the Rosary; and a concluding, surprise peek at the Japanese redemptive art of kintsugi.

Buy this book, read it, and then visit a museum with your friends. We cannot afford to lose our Christian artistic heritage. Let us keep that window open, lest those who follow us be robbed of a thousand glimpses of heaven.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image “The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament” (1509) by Raphael, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News