We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

I have just wasted ten minutes of my life reading, well…hell. I don’t know what this was from the Department of Defense.

OH, MY GOD – MY EYES ARE BLEEDING

Advertisement

NEWS: D0D Dealing With Climate Change as a Security Concern for Africans https://t.co/rVTfsRsNDX

— Department of Defense 🇺🇸 (@DeptofDefense) December 12, 2024

Literally, a brand new press release from the United States Department of Defense – official DOD News – that makes no sense at all and has no reason for even existing except to scratch some woke virtue-signaling itch

And now you must suffer as I give it a bit of a Fisking.

Combating climate change is a priority to the nations of Africa, and U.S. officials are listening and responding to those concerns, said Maureen Farrell, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for African affairs at the Defense Writers Group, yesterday.

Hear that world? The US DoD is listening…

Argle-bargle.

…African nations see the effects of climate change daily with the desertification of the Sahel region, abnormally destructive storms, flooding and more. The average temperature in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa has increased each decade since 1971 and is expected to increase further. Djibouti, a country with a large U.S. military presence, is already one of the hottest countries on the planet.

“It’s an issue that our African colleagues raise to us repeatedly in almost every engagement we have overseas,” Farrell said.

Let’s stop right there.

We all agree it’s hot in Africa. Ebola did six months or so at Camp Lemmonier in Djibouti over a winter a few years ago, so we have a good grasp of what the base and the area is like. As he’s a meteorologist, we were treated to a little deeper insights into its the weather, which he says is some of the funkiest he’s ever experienced because of proximity to.

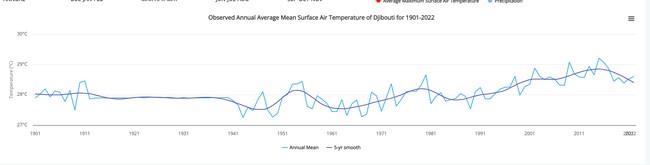

But it doesn’t take a scientist to wonder just how much hotter Djibouti’s gotten over the past 50 years or so with a claim like that because the implication is that they’re roasting. The thing is, it’s easy enough to see what that gradient has been – maybe even compare it to historical data going back further.

Advertisement

On a mean average surface air temperature chart from 1901 to 2022, yeah – you can see the temps start to bump up two-thirds of the way through. But you also see them starting to fall again as the chart ends.

Over the course of that 122 years, the total increase in mean temperature is all of .7ºC or 1.26ºF.

They have been in the middle of a drought and I can’t speak to the ‘historic’ nature of it, as the region is known for swinging wildly from one extreme to the other. Or experiencing a devastating flood seemingly right next door to a dustbowl area. It’s the nature of where they’re located – there’s a lot going on with currents converging in the oceans and atmosphere around them – and has to be accounted for prior to pointing the wagging finger of climate change blame.

…The country is particularly affected by low and irregular precipitation patterns. The climate is marked by two distinct seasons. The cool season (October-April) has mild temperatures ranging between 22°C and 30°C with relatively high humidity and sea winds. The hot and dry season (May to June and September to October) has high temperatures, which can range between 30°C and 40°C with often violent, hot and dry sand wind (khamsin). The wettest months are April, July, and August, with a monthly average of 30 mm. January, June and December are the driest months, with average rainfall of 10 mm or less. Rainfall is largely regulated by the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the climate is also susceptible to the impacts of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The country also experiences occasional catastrophic floods.

Looking at the observed seasonal precipitation numbers in the World Bank data, they’ve been through an overall worse drought cycle than this before. What I imagine is that they didn’t have the population numbers to increase the stress.

Advertisement

What I also see in the verbiage in this paragraph from the DoD is the attribution to “climate change” for ills that are entirely man-made and reversible. I’m talking about this sentence:

…African nations see the effects of climate change daily with the desertification of the Sahel region

Changes in the climate are not turning the Sahel – the western area of northern Africa tucked just under the Sahara – into a desert. Overgrazing is, says NASA.

Ebola says don’t blame the cows there so much – it’s the goats (the ‘livestock’) who come behind them and eat everything who really destroy the place.

It has nothing to do with your SUV, and shame on the DoD for implying it does.

The Sahel, or Sahelian Zone, lies south of the Sahara Desert in North Africa. This dry savanna environment is particularly prone to devastating drought years. Typically, several years of abnormally low rainfall alternate with several successive years of average or higher-than-average rainfall. But since the late 1960s, the Sahel has endured an extensive and severe drought.

Desertification occurs when land surfaces are transformed by human activities, including overgrazing, deforestation, surface land mining, and poor irrigation techniques, during a natural time of drought. Desertification in the Sahel can largely be attributed to greatly increased numbers of humans and their grazing cattle.

Most overgrazing is caused by excessive numbers of livestock feeding too long in a particular area. Extreme overgrazing compacts the soil and diminishes its capacity to hold water, and exposes the soil to erosion.

Although the relationship between drought and human influences is complex, desertification can be successfully mitigated if financial resources are available. But exploding population growth in developing African nations means that pressures on the land there will continue to intensify.

Advertisement

If developed countries would allow Africans modern farming equipment and fertilizers instead of handing solar cells to people in huts who have to use goat dung for cooking fuel, there might be less need to over-graze their livestock. They wouldn’t have to if they could efficiently grow their own fodder.

Our dustbowl of the 1930s is the classic example of ‘desertification’ that was successfully remediated with improved farming techniques and modern advances in both equipment and planting.

My friend Jusper Machgu is constantly advocating for Africans to be freed from Green bondage.

‘you have stolen my future’!

Nobody over here is worried about climate change. We have 99 problems but climate change isn’t one!

This is the best time to be alive but how we wish we concentrated on solving our biggest problems first such as hunger, clean water and cooking,… https://t.co/cDzNBWB0he pic.twitter.com/7CwY1iY6pF— Jusper Machogu (@JusperMachogu) November 28, 2024

…This is the best time to be alive but how we wish we concentrated on solving our biggest problems first such as hunger, clean water and cooking, education access, proper clothing, access to electricity, etc.

Fossil Fuels for Africa

Give them nitrogen fertilizers and diesel for tractors, let them use their own natural gas for electrical plants to light their homes at night, and to run the pumps for clean-water wells, etc.

It’s such a concept. Maybe it would chill out some of the angst.

…”We also see an increase in climate-stressed areas in terms of conflict between pastoral and farmer herder communities over the water resources and agricultural lands,” she said.

“In almost all of the sub-regions of Africa, we have tensions over droughts, flooding and agricultural productivity,” she said. This leads to increased migration, and the European allies are feeling those pressures. “As people have fewer viable farming areas, we see population flows moving to where they can sustain themselves,” she said. “And this — in many cases — means moving north from the Sahel.”

Advertisement

But, my gosh – what would a woke Dept of Defense have to write about then if somebody started to get their act together and weren’t in a constant state of tension?

Neocolonialism at its best!

GP Africa is a colonial tool funded by Western governments, NGOs and globalist groups.

There is nothing African about this alarmist group with an African name.

No wonder Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, even with its ton of oil, has to import oil all the way… https://t.co/I8tA6jkGzM pic.twitter.com/LkJgSOZQIS— Jusper Machogu (@JusperMachogu) December 12, 2024

This little message also didn’t mention part of the “tensions” during the historic drought brought on by Ethiopia’s damming of the headquarters of the Nile (thanks to Ebola for that reminder.).

This has caused tremendous heartburn in the drought-stricken region that gets little to no shrift in any discussion.

Ethiopia has built a dam on the Nile to meet 60% of its power needs. Downstream countries Sudan and Egypt are furious as this threatens their water supply. They are asking for UN intervention –– or war?

The Nile River as we know it is the large river that floods wide areas of Egypt, allowing for the farming of wheat, beans, cotton and fruit –– and tourism. But the Nile is one of the longest rivers in the world, and one of the two major sources of the mighty Nile starts in Ethiopia at what is known as the Blue Nile at Lake Tana. The Blue Nile is the source of 85% of the Nile water. The second source starts lower down in Uganda and passes through Sudan.

Over the years Ethiopia has been building a dam called the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) about 10 miles east of Sudan to supply its energy needs. Ethiopia has been building Africa’s largest hydro-electric dam since 2011. The landlocked country, which I visited this year, has one of the lowest rates of access to modern energy services, with its energy supply primarily based on biomass, followed by oil (5.7%) and hydropower (1.6%).

The main purpose of the GERD in Ethiopia is power generation, and its 13 turbines are expected to produce about 16,000 GWh of electricity annually which will double Ethiopia’s previous output of electricity and provide power to 60% of the country’s population. If you have ever visited Ethiopia you will understand how meaningful this is.

Advertisement

Maybe as a plain old saber-rattling border dispute over resources, it’s not woke enough for a feel-good, ‘we’re listening‘ DoD article that wants to hit certain virtue-signaling tickets?

How about getting back business, like fighting and winning wars? Instead of…whatever this is.

…The DOD approach is, of course, fully integrated with the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development. This combination of diplomacy, development and defense looks to build resilience with the effort concentrated right now in Libya, Mozambique and a grouping of five coastal West African countries.

“Working with them, [we] have also learned about different ways to build in resiliencies into the force,” Farrell said. “Seeing the way our Kenyan colleagues operate in northeastern Kenya is very instructive for us as we operate in Djibouti and other places where [they] experience extraordinary drought.”

Increasing the resiliency and sustainability of African nations has long-term stability and security implications: They become more self-reliant and less dependent on outside aid, with all the baggage that brings with it.

“The department’s work in this space is fundamentally about understanding, preparing for and adapting to a changing strategic environment in which we cannot afford to fail,” Farrell said. “The consequences of inaction on climate will be severe, and our allies and partners will face growing security challenges as a result.”

Hegseth can’t get confirmed a minute too soon.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News