We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

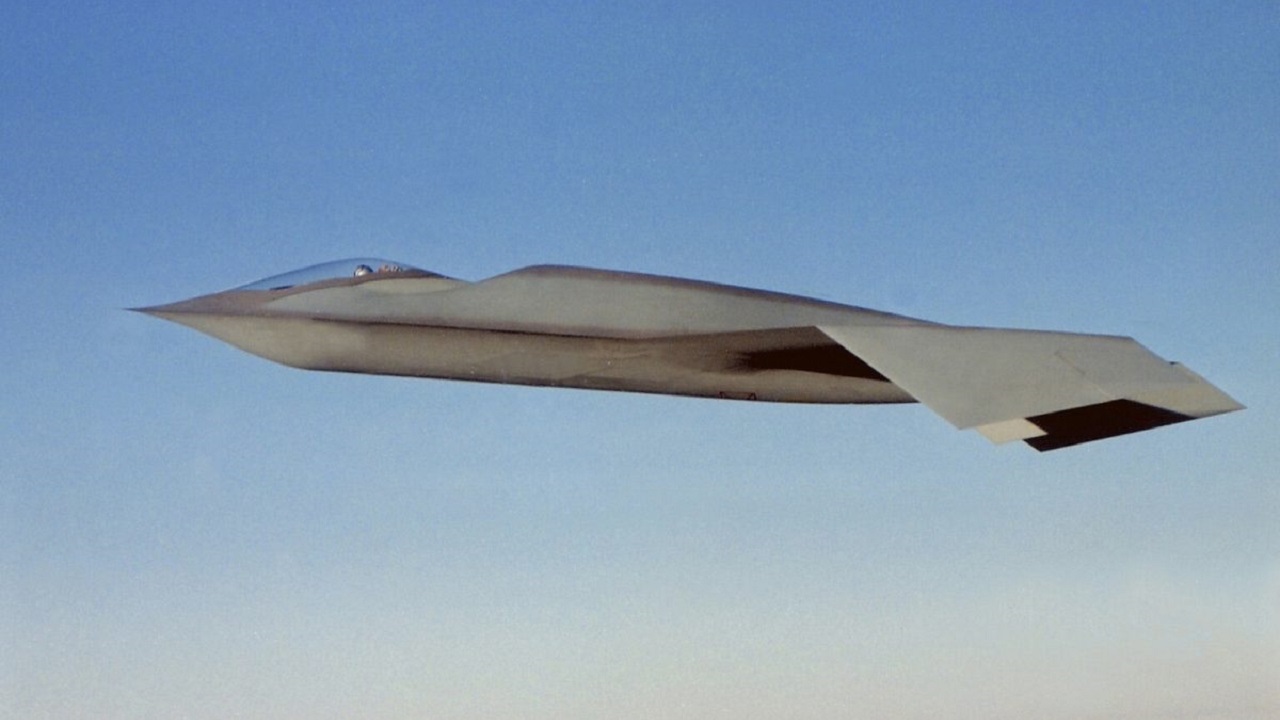

Key Points: The YF-118G Bird of Prey, developed by McDonnell Douglas’ Phantom Works in the 1990s, was a stealth aircraft prototype designed more for innovation than operational use.

-Created under tight budgets, it used rapid prototyping, composite structures, and off-the-shelf components to revolutionize stealth technology.

-With its tailless design, gull wings, and a cruising speed of just 300 mph, the Bird of Prey proved the potential of cost-efficient stealth innovation.

-Though it never entered service, its breakthroughs influenced later projects like Boeing’s X-45A UCAV. Today, it remains an icon of ingenuity, displayed at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

YF-118G Bird of Pray Stealth Fighter: We Explain

Throughout the 1990s, a team of engineers from McDonnell Douglas’ Phantom Works developed and tested a unique stealth fighter shrowded in the secrecy of Area 51, known to most as the Bird of Prey. Unlike most stealth programs, the Bird of Prey, developed under the alias “YF-118G,” wasn’t aiming for operational service, but elements of the design and production process are still working their way into Uncle Sam’s hangars to this very day.

But perhaps the most lasting contribution this incredible and exotic airframe has made to America’s defense apparatus was in its audacity and subsequent success. While most stealth programs are known for their high cost, the Bird of Prey went from a pad of paper to the skies over Area 51 for less than the cost of a single F-35 today.

The stealth revolution

In October of 1983, the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk secretly entered service for the U.S. Air Force, marking the world’s first operational stealth aircraft. While the Nighthawk carried the “F” prefix designated to fighters and was even colloquially known as the “stealth fighter,” the Nighthawk was actually no fighter at all. With no onboard radar, no guns, and a payload capacity limited to two 2,000 pound bombs, the F-117 Nighthawk was an attack aircraft masquerading as a fighter, but let there be no mistake: it was an attack aircraft unlike anything the world had ever seen.

After decades of focus on fielding faster, higher-flying aircraft as a means of defeating enemy air defenses, the Nighthawk served as a pivot point for the very direction of aviation technology and air warfare doctrine among the world’s most powerful nations. The Nighthawk was slow and cumbersome compared to the F-15s and F-16s in Air Force hangars, but in a world where America’s smallest fighter carried a radar cross-section of 82 square feet, the F-117 carried a radar cross-section of only slightly more than a tenth of an inch (0.11 inches). For all intents and purposes, the F-117 Nighthawk was practically invisible to enemy radar.

Less than a decade later, as Lockheed’s YF-22 competed with Northrop’s YF-23 for the Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter contract, bringing the world’s first true stealth fighter to fruition, the team at McDonnel Douglas’ Phantom Works had stealth aims of their own, and they had just the man they needed to pursue them.

A Secret Pioneer of Stealth Aviation

Unlike Lockheed and Northrop’s high-performance stealth fighters that benefitted from direct tax funding, McDonnell Douglas alone was picking up the tab for their new stealth aircraft’s development. In order to be sure all that money didn’t go to waste, they tapped Alan Wiechman to head up the effort.

YF-118G Bird of Prey. Image Credit: Erik Simonsen illustration

Wiechman cut his stealth teeth at Lockheed’s Skunk Works, where he worked on the Have Blue program and its operational successor, the aforementioned F-117 Nighthawk, before helping to develop Lockheed’s Sea Shadow, aimed at fielding stealth warships for the U.S. Navy. After McDonnell Douglas’ proposal for the Advanced Tactical Fighter program was rejected by the Air Force in favor of Lockheed’s YF-22 and Northrop’s YF-23, McDonnell Douglas hired Wiechman to get their low-observable efforts on track, and to help found their Phantom Works division.

In the annals of aviation history, Wiechman’s name doesn’t pop up as often as other legendary engineers of the day like Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. In fact, Aviation Week ranks him as perhaps the “lowest profile” engineer among their list of “Secret Pioneers of Stealth Aviation.” But widespread recognition isn’t always a good measure of accomplishment, and indeed, Wiechman’s contributions to stealth aviation are so numerous, that he received a Technical Achievement Award from the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) for his work in Low Observable aircraft design before the Bird of Prey was even declassified.

“Because of Wiechman’s work, the United States gained a 15-year lead over potential adversaries that it has not relinquished, and the effectiveness of his designs and products has been thoroughly proven in combat operations,” the award read.

Phantom Works and the YF-118G program

Work began in 1992 under the innocuous enough-sounding name of YF-118G. Wiechman’s team at the Phantom Works had to be budget-conscious, so as they went about designing their new stealth aircraft, they leveraged a then-novel approach of rapid prototyping. Rather than designing physical prototypes, subjecting them to testing, making changes, and fielding new prototypes for further testing, the Phantom Works team used computers to aid in their design work, simulating performance to the best of the era’s computing abilities. As a result, they were able to produce prototype components that were far closer to the finished product than previous approaches would allow.

But that wasn’t the only way the YF-118G team got creative in their approach to building this new aircraft. They also leveraged cutting-edge single-piece composite structure designs that eliminated many of the body panel seems that can compromise an aircraft’s stealth profile. Producing aircraft with no substantial seems, or tiny gaps between body panels attached to the aircraft, remains one of the more challenging aspects of stealth aircraft construction. In fact, some argue that it’s something Russian stealth fighter programs continue to struggle with to this day.

YF-118G. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

But Wiechman and his team weren’t set on reinventing every wheel, so they also leveraged as many off-the-shelf components as they could to both keep costs down and expedite their design process. The Pratt & Whitney JT15D-5C turbofan engine, which produced just 3,190 pounds of thrust, would have been more at home in a Cessna business jet. The ejection seat came from an AV-8B Harrier, the control stick and throttle from an F/A-18 Hornet, and the rudder pedals came from an A-4 Skyhawk.

Air Force Test pilot Colonel Doug Benjamin once joked that “the clock was from Wal-Mart and the environmental control system was essentially a hairdryer.”

By 1996, four years after the program started, Wiechman’s team had a flyable prototype ready to prove the efficacy of their approach. The single-engine, single-seat technology demonstrator they’d constructed stretched some 47 feet, slightly longer than an F-16 Fighting Falcon. Its angular gull-shaped wings diverged dramatically from other fighter designs, angling up and then down for a total span of just 23 feet, or ten feet shorter than the F-16. But the most conspicuous departure from traditional fighter design was its blended fuselage and complete lack of tail section.

The design took a holistic approach to stealth, reducing radar, infrared, visual, and acoustic signatures through its shape, the use of flexible or movable covers to conceal gaps, and by burying its engine deep within the fuselage behind a curved inlet duct and in front of an infrared and acoustic defusing exhaust outlet.

Once completed, the aircraft’s strange shape and aggressive posture evoked thoughts of the looming warship operated by Star Trek’s warrior race the Klingons, earning it the name Bird of Prey after the ship first depicted in “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.”

YF-118G. Image Credit: Boeing.

The YF-118G Bird of Prey takes to the skies

On September 11, 1996, the Bird of Prey took to the skies over Groom Lake (also known as Area 51) for the first time with Air Force Colonel Doug Benjamin at the stick. Much like its Bird of Prey namesake that would cloak to hide from enemy starships, Boeing’s Bird of Prey relied on stealth rather than impressive performance to get the job done.

Col. Benjamin brought the aircraft off the ground and left its landing gear extended, identifying the first of a number of problems. Throughout wind tunnel testing the platform had performed well, but all of the tests were conducted with the landing gear retracted. Benjamin soon realized the drag created by the gear was at least three times worse than they had anticipated. The aircraft suffered from stability issues as well, which were slowly and meticulously worked out in subsequent flights.

In the following three years the team would execute 37 more successful flights with the single Bird of Prey prototype they’d constructed, flown by Benjamin and two Boeing test pilots, Rudy Haug and Joseph W. Felock III.

Despite its tailless design and gull wings, the aircraft was considered aerodynamically stable without the sort of computer correction modern stealth fighters rely on by the time it took its final flight in 1999.

With a cruising speed of only around 300 miles per hour, the stealthy aircraft was slower than a C-130 Hercules and its maximum operational ceiling of 20,000 feet meant it could fly less than half as high as a P-51 Mustang from World War II, but like the F-117 Nighthawk Wiechman worked on before it, the Bird of Prey wasn’t aiming to outfly the fighters of its day. Its goals were much further reaching than that.

YF-118G. Image Credit: Boeing.

Not only had the Phantom Works team proven that they too could build a stealth aircraft, they had managed to do it all for under $67 million. Adjusted for inflation to today’s currency, that means Wiechman’s Phantom Works successfully designed, prototyped, and flew a clean-sheet stealth platform for around $111 million, or less than the cost of buying a single F-35B today.

“Early investments in technology demonstration projects such as Bird of Prey have positioned Boeing to help shape our industry’s transformation,” Jim Albaugh, president and CEO of Boeing Integrated Defense Systems, said in 2002.

“We changed the rules on how to design and build an aircraft.”

The Bird of Prey Legacy

In 1999, Boeing’s Bird of Prey took flight for the last time, but that wasn’t quite the end of its story. The breakthroughs and lessons learned throughout the program soon found their way into another platform that made its first flight just months before the Bird of Prey was finally unveiled to the public in 2002; the X-45A Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle.

Like the YF-118G Bird of Prey, the X-45A was a product of Boeing’s Phantom Works, but unlike its Klingon cousin, the X-45A was designed to fly autonomously. According to Boeing, the X-45A’s design was largely derived from the Bird of Prey program, with the UCAV adopting elements of its predecessor’s radar-defeating angular design and unusual dorsal intake. Boeing has also credited some of the design techniques leveraged for the Bird of Prey in their development of the X-32, which ultimately lost out to Lockheed Martin for the Joint Strike Fighter contract just one year after the Bird of Prey program was shuttered.

YF-118G. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Today, there are no platforms in service that can draw a direct lineage to Alan Wiechman’s unusual Bird of Prey, and that may be part of the reason it’s not a frequently discussed facet of the American stealth technology race that came at the twilight of the Cold War. But for a short time in the 1990s, the Phantom Works proved that it doesn’t always take a bottomless budget and twenty years’ worth of delays to produce a stealth fighter, and that’s a lesson America has struggled to learn in the decades since the Bird of Prey prowled the skies over Area 51.

You can see the only YF-118G Bird of Prey ever constructed today at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the museum’s Modern Flight Gallery, placed right above the museum’s F-22 Raptor.

About the Author: Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran who specializes in foreign policy and defense technology analysis. He holds a master’s degree in Communications from Southern New Hampshire University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Corporate and Organizational Communications from Framingham State University.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News