We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Last month, in an interview with Tucker Carlson, J.D. Vance said he worried about the U.S. government bond market in the early stages of a Trump presidency. Because of Biden-Harris spending, the U.S. is adding about $2 trillion to the national debt every year, he said, and “The only thing that makes that serviceable is that interest rates are still pretty low.” If interest rates go much higher, say to 8 percent, “that can become a huge spiral that could take down the finances of this country.”

Vance said that international investors and foreign countries — beneficiaries of globalization — could try to take down the new Trump administration by selling U.S. government bonds, which would cause interest rates to rise sharply. Vance noted we saw this in Britain in late 2022, when newly elected Prime Minister Liz Truss came out with a plan of tax cuts and, partly due to the market reaction and partly due to Bank of England actions, British government bond yields spiked, and many investors and pensioners faced large losses. Truss’ government was taken down in less than two months as a result.

Vance said the immediate fix to this bond market risk is twofold. First, staff the Treasury Department with intelligent people. Second, create flat tariffs (not varying in rates for special interests) that can both generate revenue and bring jobs and economic activity back to the U.S., adding to the tax base.

Finally, Vance hinted that spending cuts could be pursued. He noted that federal spending in 2019 was $4.5 trillion per year and is now above $6.5 trillion in 2024. Vance made sure to point out that of this $2 trillion increase, only a very small amount comes from Social Security and Medicare spending — instead, the problem of overspending is because the government still hasn’t pulled back spending from the Covid response. Vance is right, and it should be noted that at least some of the spending increase between 2019 and 2024 (about $500 billion) is additional interest on the national debt. This highlights Vance’s overall concern — if interest rates rise, the cost of servicing the debt grows even higher, which could in turn cause interest rates to rise further as investors worry about the high cost of debt service and want a better return on investment given the elevated risk.

Added Risk of a Bond Market Blowout

There’s an added, hidden risk of a bond-market rate blowout that could face the next administration. As federal spending shot up under the Biden-Harris administration, and interest costs increased as inflation increased (requiring more debt to be issued to pay for the interest), the risk was that a massive increase in government debt issuance would suck liquidity out of the real economy (and stock market). This is because the dollars used to fund the government debt have to come from somewhere, and in ordinary circumstances they come from the real economy.

To avoid this, the Biden-Harris U.S. Treasury under Janet Yellen shifted to issuing very short-term government debt (Treasury bills, maturing in less than a year) in 2023. This doesn’t make sense from a financial perspective, because at the time shorter-term debt cost more than longer-term debt (the yield curve was inverted), and because this reliance on short-term financing makes the U.S. government debt load even more at risk if interest rates spike, because a larger share of government debt needs to be rolled over at market rates every year.

In 2018, the share of Treasury bills (maturing in a year or less) as a percentage of the total debt was 15 percent. Now it stands at 22 percent, a roughly 50 percent increase, adding to the amount of Treasury bills outstanding by $10 trillion. This is a huge increase, given how many trillions of dollars need to be rolled over year-to-year.

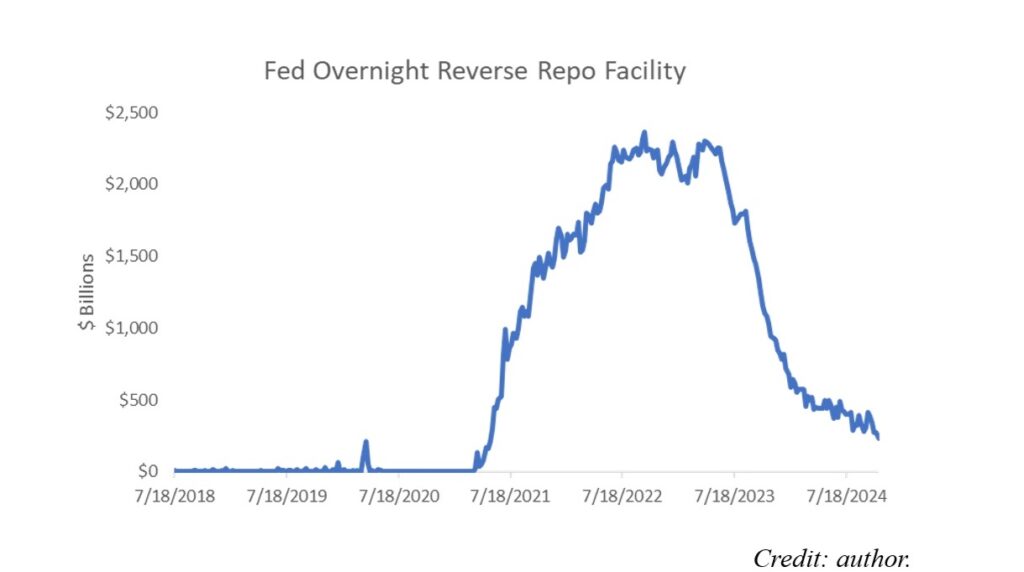

Why did the shift to issuing short-term debt, more risky for the country in the long run, delay the hit to the economy from the rising debt load? Because of something called Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP), which is a facility at the Federal Reserve that was used to suck up excess cash in the system during the Covid stimulus to avoid money market rates going negative (money market funds are ultra short-term funds where corporations and investors park cash to get a small return). If Treasury issues short-term debt maturing in less than a year at a slightly higher rate than the rate available in the ON RRP facility at the Fed, then money market funds with dollars in the ON RRP have an incentive to pull cash out of the ON RRP and buy the newly issued short-term Treasury bills instead. This avoids a liquidity hit on the economy, as cash is coming from the ON RRP, not the broader economy. But this only works while the ON RRP still has cash in the facility.

Turns out the ON RRP is set to get fully drawn down just on time to get through the U.S. election. This, of course, is no accident. To put it bluntly, the Biden administration made America’s debt worse to make the economy look better and hide the debt problem through an election, leaving Trump’s new administration a potential time-bomb.

Right now, Treasury has a roughly $800 billion cash balance. But this will quickly get drawn down as the government is spending nearly $2 trillion more than it takes in every year. The Treasury needs to issue more debt in the next quarter, to pay for all the government overspending — somewhere between $500 billion and $1 trillion of new debt in the first quarter of 2025 alone!

But this newly issued debt can’t be short-term Treasurys any longer — for one, the U.S. Treasury is already way over its skis on relying on short-term debt. Second, because the biggest reason to over-rely on short-term debt issuance (the ON RRP facility) is almost depleted. Now, this new debt issuance next quarter will impact liquidity and the broad market, whether it be via higher interest rates, lower stocks, a crowding out of private sector investment, or all of the above.

Of course, the Biden-Harris Treasury does not present its actions as nakedly political. The Treasury Department says it is waiting to issue more notes and bonds (longer-term debt) until the Federal Reserve stops selling off the Fed’s portfolio of notes and bonds built up over the last 12 years (known as QT, or quantitative tightening, which is the reverse of the Fed’s quantitative easing, which is buying government bonds with electronically created money).

But the Fed’s job isn’t to bail out Washington overspending. Whether the Fed does its job or not is another story, but even an activist (read bad) Fed might delay ending QT if inflation is stubbornly high. And even if the Fed stopped QT entirely, or began to buy bonds again (a very bad move for the working class), a shift in Fed policy won’t be enough to offset the massive Treasury issuance set to happen in 2025.

What Can a New Administration Do?

Vance is right about tariffs and staffing smart people at the Treasury. But if the bond market sees a sharp rise in interest rates, these policies might not provide the complete answer. The risk here is very real — again, because of the rollover risk of having 22 percent of the Treasury debt in short-term bills, the interest cost of servicing the national debt could rise quickly, prompting further long-end issuance to pay for the interest, flooding the market with notes and bonds and causing rates to move even higher, which then causes even higher interest costs. This is the snowball effect from hell, and could derail the new Trump administration.

First, the new administration needs to clearly and plainly communicate why this is happening in a way normal people can understand: “The Biden-Harris administration papered over the true cost of America’s debt load with a Covid-era pool of money set up by the Fed. Biden-Harris knew this would only get them through the election. Now, here’s how we move forward to fix this problem we were given.” This can be communicated well before any bond market problems, and whether yields spike or not.

Second, more must be done on overspending. One approach could be capping non-defense, non-Social-Security, non-Medicare spending items in nominal dollars as of 2024. Instead of large cuts, lower spending can be phased in. Other items should be specifically examined. For example, the Democrats used accounting gimmicks to claim the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) would cost $391 billion between 2022 and 2031, but the real cost is estimated to be as much as $1.2 trillion. There are provisions of this law that the next administration may want to keep, but there is plenty of room to rein in the uncapped nature of this law. Tax cut plans must also be prioritized: Cut taxes on overtime and tips well before any roll back on the SALT (state and local tax) deduction cap that would benefit the blue-state rich.

Third, if interest rates on the long end of the curve (longer term government debt) drop, Treasury must rapidly shift more of the U.S. debt outstanding from short-term bills into longer-term debt, to negate the risk of higher interest rates on government borrowing costs. Re-shoring, healthy food, and de-coupling from China are extremely beneficial policies to pursue, but they are also marginally inflationary, at least initially. There are other factors driving inflation higher, including the aging population relative to the percentage of working-age Americans.

A plan to rely less on short-term funding is smart not just over the next several years, but over the next decade.

This individual is granted anonymity since publishing an article on The Federalist would credibly threaten close personal relationships, their safety, or their jobs. We verify the identities of those who publish anonymously with The Federalist.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News