We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

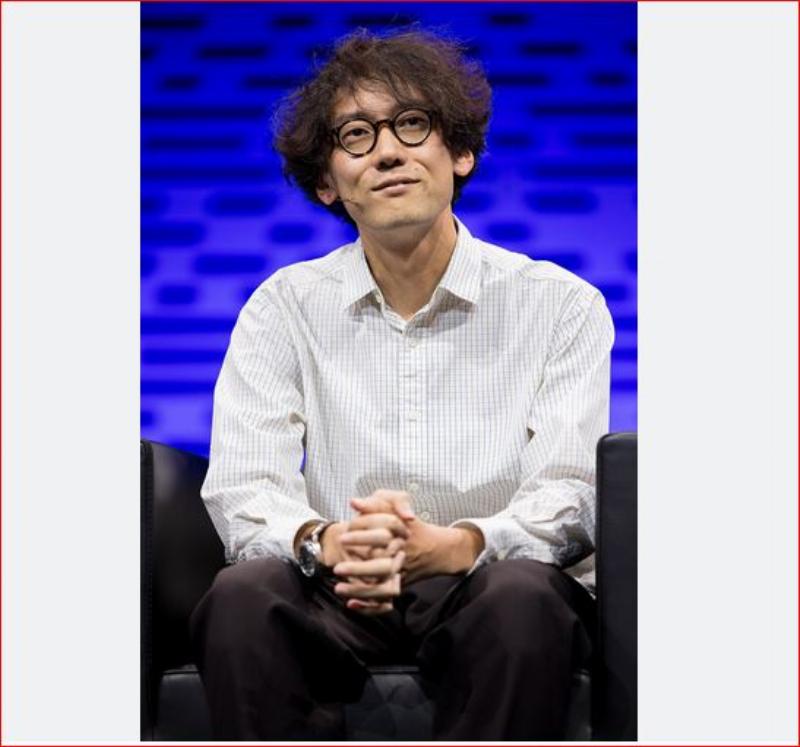

A deluded, muddleheaded intellectual of the far Left has gained traction over the last four years. His name is Kohei Saito, and he declares rather blithely that “capitalism is dead” and that “degrowth communism” – a term of his coinage—is the future.

It would be easy to dismiss him as a Quixote or a crank. But raising the bogey of an ecological crisis to push for a global slowdown – in terms of population, economy, production, pollution, everything – is an old ruse of academics, industry, governments, and their elite controllers who aim to establish a new world order. And that is why Saito’s popularity – despite his vague pronouncements, often wrapped in dense theory – is worrisome.

Magazines across the political spectrum, including avowedly radical ones, have panned Saito’s ideas: the New Yorker, reviewing one of his books and sketching a brief profile of him, takes an aloof, skeptical view; the Atlantic dismisses his theory as “economically dubious and politically impossible;” the Jacobin says he is not only incorrect, he spells disaster for the left and the environmental movement; and Counterfire declares that he “misunderstands” Marx.

Yet this unlikely Marxist philosopher from Japan, aged 37, is becoming influential among young leftists enamored with the hodgepodge of eco, equity, and woke activism. He is a product of the disenchantment with economic prosperity and concern for the environment felt by many young Japanese after the 2008 economic crisis and the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Attracted to Marxism in college, he made an academic career of it, focusing on Marx’s late, unpublished writing – notebooks, mainly.

Were it not for his surprise bestselling books, Saito would have remained obscure. But Capital in the Anthropocene (in Japanese, 2020), its English translation Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto (2024), and Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism (2023) – catapulted him to fame, first among Japanese youth, then worldwide.

Saito’s big claim – that Marx in his later years became an eco-socialist, even before the term was invented – came in his 2017 work Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism. The claim has been debunked by many Marxist theoreticians, and yet is catalyzing the current degrowth movement. The book is replete with ludicrous passages such as the following:

For example, the form of a desk that labor provides to the “natural substance” of wood is “external” to the original substance because it does not follow the “immanent law of reproduction.”

Perhaps it takes sufficient Marxist brainwashing for such writing to spark green epiphanies in those swearing by Saito, who wants to end “mass production, mass consumption, and mass waste.” In short, he wants almost all economic activity to stop, and envisions a utopia where people minimize needs and communes own and control production with an undefined authority dictating how much is enough.

Be that as it may, the degrowth strategy for establishing a new world order dates to the late 1960s, and has insidiously gained influence over the decades to create the present milieu of fear in which the extremes of Saito’s propositions are taken seriously. It was in 1968 that the Club of Rome, a restricted society of elites, was formed to create a framework for a new world order that would overcome global problems, including environmental ones, inherent in prosperous economies. That began the assault on the benign ethos of capitalism, innovation, and freedom.

The Limits to Growth, a 1972 report commissioned by the club, concluded that in a hundred years the world would run out of resources. But the report failed to consider behavioral changes over time and the ability of the human spirit of innovation to find numerous solutions that would together forestall the doomsday prediction.

The report came in the wake of Paul R. Ehrlich and Anne Ehrlich’s alarmist book The Population Bomb (1968), which warned that by the 1970s, overpopulation would cause worldwide famine, social unrest, and pandemics. The Ehrlichs suggested bringing the population growth rate to zero, or even a negative value, through draconian measures. Today’s degrowth/zero growth movement seeks to apply similar strictures across the board to control all aspects of the economy and human life.

The Agenda 21 and Agenda 30 action plans, introduced by the United Nations in 1992 and 2015 respectively, took those ideas forward. Introduced as a “comprehensive blueprint for the reorganization of human society,” they went on to integrate social justice considerations, net zero emission, and other impossible goals. Looming environmental crises of severe proportions were presented to justify government intrusion and control.

The Great Reset, advanced by the World Economic Forum (WEF), is another iteration of this idea. In this effort, big corporations have allied with governments to actively lobby for regulations that will cripple small companies, kill competition and grassroots innovation, centralize trade, redistribute manufacturing, wealth, and jobs across national borders, and restrict the use of natural resources. Its elite proponents, who hope for ultimate control over people, claim this will transform capitalism, creating a kind of corporate socialism in which “you will own nothing, and you will be happy.”

Saito, though, is so far left that he distrusts the United Nations; he also distrusts purported efforts to transform capitalism. A measure of his confusion and chimerical idea-mongering comes across in this exchange with the Atlantic. Degrowth on its own, he told the magazine, had bad branding (a thoroughly capitalistic concept, please note!), so the solution was to add “another very negative term: communism.” And a measure of his acuity is evident in how “degrowth communism” has caught on with leftist, anarchist, and woke movements on campuses and elsewhere.

Conservative author and political commentator James Lindsay pointedly declares in one of his recent New Discourses podcasts that degrowth is communism and a death cult. Degrowth calls for the acceptance of lower GDP, fewer material goods, and lower standards of living under a planned and controlled economy.

It demands a lowering of our expectations for quality of life so that – ostensibly – the planet can be saved and we can have greater “abundance” as defined by more quality and a oneness with nature in place of capitalism’s intrinsically impoverished abundance of commodities. In the New Yorker piece, Saito makes a point about not buying “fundamentally useless things.” It is, of course, entirely irrelevant that his family of four lives in a three-story house in Greater Tokyo!

Lindsay views the degrowth movement as a planned elimination of “unsustainable” Western economies that will generate less energy, decrease food production, and ultimately reduce the population. He says this is impossible, for one cannot have high standards of living with low energy production. The reality of this utopian fantasy, he says, is “starving while you freeze to death in the dark.”

The actual goal of degrowth is, of course, to achieve communist authoritarianism: the end of free markets, individual liberty, and free will. As Lindsay says, it’s “a strategy to break the West economically and force it into communist policy using environment concerns as the justification.”

And that is why soft-spoken, self-deprecating Saito – muddleheaded as he is – and his ideas – amalgamated as they are with communism now – are both dangerous. For a taste of his writing, three of his books are available for reading, quite appropriately, on an anarchist website.

Image: Martin Kraft, via Wikipedia // CC BY-SA 4.0

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News