We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Like every person, I live in two worlds: the temporal and the eternal. I now see that every person I meet in ordinary, daily affairs is part human and part divine, a storytelling self, often confused, dislikable, and in pain, but always transient, and a mysterious self, deathless, an image of God, worthy of unconditional love.

My previous essay in this series, “The Human Being: The User Manual,” established that the world animals live in is like a small, poorly furnished room, for they have narrow, limited perception. A frog sees small moving objects, not stationary flies or worms. A mother turkey does not see her chicks. Only their chirping keeps her from attacking them as enemies.

Of all the natural creatures, only human beings can grasp a whole. The study of animal perception re-discovered the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens—the capacity to be connected to all that is, a fundamental principle of every wisdom tradition.

The Curse of Social Living

Sophocles enunciated 2,500 years ago that “nothing that is vast enters the life of mortals without a curse,”[1] wisdom that implicitly recognizes that no perfect social order can be created; said in colloquial English, Nothing great without a curse.

The curse of social living is that every society implants ideas and instills habits of thinking that limit its members to a particular perspective, one that, as a general rule, is contrary to human nature and destructive to neighboring societies. The paradox is that social living greatly extends our capabilities and yet limits us. Capitalism tells us that we are economic beings; nationalism tells us that our ultimate destiny is the fate of our Nation-State; democracy tells us we are autonomous, isolated individuals, all false and often disastrous understandings of the human person.

In the ancient world, the constant reference point is the group. To be separated from the group is to lose one’s identity or even one’s existence. Prince Modupe of the So-So tribe reports that at the turn of the century in Africa, “Any destiny apart from the tribe was, of course, beyond the limits of either imagination or intuition. It was as unthinkable as that one of the bright orange legs of a millipede should detach itself from the long black body of the creature and go walking off by itself.”[2] Chief Standing Bear testifies that for a Lakota Indian “to cut himself from the whole meant to lose identity and die.”[3] If I am a member of a group-centered culture, I believe that I am social by nature and that without the group, I would not exist.

Ethnologist S. M. Molema, writing about his own people, the Bantu tribe, points out that in premodern Africa a person’s “actions are controlled by iron reins of tradition, his conduct is constrained by rigid custom. His very words are often a formula.”[4] Prince Modupe confirms Molema’s observation: “When I lived with my people in Dubricka, all of my opinions and judgments were formed by them, by my mother and the elders and the teachers in the Bondo Bush. A youth was taught never to question the validity of anything an elder said.”[5] Hopi children frequently hear from their parents, “Your old uncle taught us that way; it is the right way” and “Listen to the old people; they are wise.” Many Inuit and aboriginal tribes do not even have a word for disobedience. Group expectations are so strong that the young learn to follow custom unthinkingly, and as a result, such ancient peoples have no system of law and punishment.

The advantage of the ancient habits of thinking is that they are founded on their social nature; the curse is that their nearly unlimited freedom is not recognized, nor is their capacity to command nature. When the Hopis say, “Our way of life was given to us when time began,” they praise that their way of living never changes, unlike modern Westerners where nothing seems fixed in social and economic life.

Tocqueville, in “Concerning the Philosophical Approach of the Americans,” an absolutely brilliant chapter of Democracy in America, argues that since an American always begins with the self, each citizen forms the intellectual habit of looking to the part, not to the whole, and as a result is a Cartesian reductionist: “Of all the countries in the world, America is the one in which the precepts of Descartes are least studied and best followed.” Tocqueville explains this paradox. In a modern democratic society, the links between generations are broken; consequently, in such a society, men and women cannot base their beliefs on tradition or class. Social equality produces a “general distaste for accepting any man’s word as proof of anything.” Therefore, “in most mental operations each American relies on individual effort and judgment.” Like Descartes, each American employs the philosophical method to seek for the reason of things for oneself and in oneself alone.[6]

First, let me note that to grasp the habits of thinking of premodern peoples, I had to imaginatively use published accounts by Africans, Native Americans, and Chinese, while to understand modern habits of thinking, I just had to look at myself.

As a member of a modern democratic culture, I could not base my beliefs on tradition, custom, or class, because the links between “peasant and king”[7] no longer exist in Modernity. By the sixth grade, I did not understand myself in terms of either family or nature; my Romanian heritage meant nothing in America, and although I spent my boyhood summers playing in rural Michigan, I never received any instruction at home or in school about my connection to nature. I understand myself as an isolated, autonomous individual. My constant reference point, then, was always myself. Consequently, I formed the habit of always thinking of myself in isolation from others, and this habit carried over when I thought about things. Thus, culture instilled in me the modern habit of thinking: To understand something isolate it, so it exists apart from all relations.

Hence, I believed that every part could be separated from the whole and that the whole could be understood as a collection of parts. With such a habit of mind, I attempted to understand everything in terms of its parts. But the smallest parts of anything are material. Consequently, the culturally-given habit of thinking the whole is a collection of parts made me a firm believer in materialism—I could not think any other way. I just “knew” that the universe, including all aspects of human life, was the result of the interactions of little bits of matter.

Tocqueville holds that in all cultures materialism is a serious malady, but democracies favor “the taste for physical pleasures and this taste if it becomes excessive, soon, disposes men to believe that nothing but matter exists.”[8] Most Americans are materialists, as Tocqueville suggests.

A Killer Argument That Disproves Materialism

Modern science inevitably attached itself to the philosophy of materialism, the theory that holds that every object, as well as every act in the universe, is matter, an aspect of matter, or produced by matter. Experiments measure what happens when matter is manipulated; thus, the toolbox of science is limited to mass, electrical charge, internal forces, and other measurable properties of matter. Don’t think I am suffering from the narrow viewpoint of a physicist. Today, the quaint, old-fashioned psychology “experiments” with twenty or so undergraduates trying to make a few dollars must be confirmed by brain scans.

Experiments, by their very nature, deal only with matter, either complex structures like the brain or simple but baffling objects like the proton. Experiment alone, however, does not lead to materialism; a philosophical belief must be added. In the Proem to his Great Instauration, Francis Bacon envisaged the “total reconstruction of sciences, arts, and all human knowledge, raised upon the proper foundations,” that is, upon experiment. The belief that science is the only road to truth sets the goal of modern science—to show all phenomena in the universe result from the workings of physical matter.[9]

However, brain function alone cannot explain the most obvious human experience—we perceive. Textbooks typically gloss over the profound difference between sense perception and its necessary physical components. Regarding vision, Crick, a materialist, confesses, “We really have no clear idea how we see anything. This fact is usually concealed from the students who take such courses [as the psychology, physiology, and cell biology of vision].”[10] Physicist Erwin Schrödinger gives a killer argument that materialism is incapable of explaining how we see.[11]

Suppose sunlight is reflected from a red apple into the eye of a landscape painter. The sunlight passes through the lens of the eye and strikes the retina, a sheet of closely packed receptors—4.5 million cones and 90 million rods. Activated by the incoming sunlight, chemical changes occur in the rods and cones, which are then translated into electrical impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain. Further electrical and chemical changes take place in the brain. This description is complete in terms of the physiology of seeing; however, the sensation red has not appeared in this materialistic account of perception. The landscape painter experiences the red of the apple, not the various chemical and electrical changes necessary for seeing.

Here is an amusing example of why our interior life does not result from brain function alone. During the day, adenosine builds up in the brain to register the time that has elapsed since a person awoke. When adenosine concentration peaks, a person feels the irresistible urge to sleep. The concentration of adenosine and the feeling of sleepiness are in totally different realms. No matter how much a neuroscientist probes the brain with scans and chemical assays, she will never find sleepiness.

Two Kinds of Wholes

Contrasting modern biology with Newtonian physics, we see that there are two kinds of wholes, organic and composite, that differ radically in how a part is related to the whole. An open encounter with any living organism reveals that each part, in some way, always contains the whole. Consequently, a part is not separable from the whole, for if it could be separated, the part would no longer exist. Consider a jack rabbit in the desert Southwest. The DNA in every cell of its body is unique to this individual jack rabbit. The entire rabbit is contained in every cell of its body; in a liver cell, for instance, is the information to build a pancreas, an eye, a brain, and every other part of the rabbit. If the whole were removed from a cell, it would be destroyed; no rabbit cell can exist without its DNA. The rabbit cannot be explained solely by its organs or by its cells because each of these parts also contains the whole.

Even the environment of the rabbit is present in some way in its parts. The coyote is present in the rabbit’s powerful back legs, desert plants in its sharp teeth, the earth’s gravitational pull in its bones, an oxygen-rich atmosphere in its lungs. The history of the universe is also present in the rabbit. The calcium atoms in its bones, the iron atoms in its red blood cells, indeed, every chemical element in its body came from stars that exploded billions of years ago. The matter of the rabbit is literally star stuff, and therefore the Big Bang, galaxies, and stars are present in the rabbit. Remove all traces of the atmosphere out of the rabbit, then its ears, lungs, and blood would no longer exist. Remove the earth’s gravity from the rabbit, then its bones would vanish. Remove the Big Bang, and nothing exists. The rabbit exists only as a part of a larger whole. If all the rabbit’s relations to its world could be eliminated, then it would cease to be, and, of course, the same is true for us.

Reductionism, then, rests on the assumption that the part is completely separable from the whole, and understandable in and of itself, which clearly is false for living organisms. A living organism must be understood as a whole, not as a summation of genes.[12] The failure of reductionism in biology does not mark the failure of science, but only the replacement of an unworkable assumption with a new mode of understanding that recognizes that in a living organism the part can only be understood in terms of the whole.[13]

Unlike the organic wholes of biology, the wholes of Newtonian physics are composite in that they can be separated into parts without destroying or altering the part. In Newtonian physics, the motion of a whole body is determined by the motion of its parts. The gravitational attraction of the Sun on each part of the Earth causes the entire Earth to move in an elliptical orbit around the Sun. Planets, clouds, oceans, and manmade objects do not possess the unity that organisms have. A lug nut from a 2003 Toyota Land Cruiser does not uniquely determine the individual vehicle it came from, unlike a red blood cell from a rabbit. For lifeless matter, the part is separable from the whole, and in this very limited region of nature, the principle of reductionism does apply.

A few scientists, like geneticist Richard Lewontin, understand that the cultural influence that permeates science “comes in the form of basic assumptions of which scientists themselves are usually not aware yet which have profound effect on the forms of explanations.”[14] He adds that reductionism—“that the whole is to be understood only by taking it into pieces, that the individual bits and pieces, the atoms, molecules, cells, and genes, are the causes of the properties of the whole objects and must be separately studied if [scientists] are to understand complex nature”—is a cultural belief that stems from individualism.[15]

Science Cannot Write a User Manual for the Human Being

The Grand Narrative of Science is defined by its Central Dogma, enunciated concisely by biologist H. Allen Orr, “The universe, including our own existence, can be explained by the interactions of little bits of matter.”[16] In the same vein, Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA, preaches that “‘you,’ your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.”[17] Psychologist Joshua Greene and neurobiologist Jonathan Cohen expound that “every decision is a thoroughly mechanical process, the outcome of which is completely determined by the results of prior mechanical processes. Every human action can be explained mechanically.”[18]

The Grand Narrative of Science denies responsibility for the action of any individual human being. “Any crime, however heinous, is in principle to be blamed on antecedent conditions acting through the accused’s physiology, heredity, and environment,” Richard Dawkins claims.[19] We humans cannot accept such a position “because mental constructs like blame and responsibility, indeed evil and good, are built into our brains by millennia of Darwinian evolution.”[20] In Dawkins’ view, a jury trial to determine guilt or innocence makes as much sense as a man beating his car with a tree branch because it refuses to run.

In such a world whose fundamental constituents are quarks and leptons, the human being as understood by Plato and Aristotle is false, and nature is not a guide for human living. Furthermore, modern technology has caused nature to recede from everyday life. Literary critic Sven Birkerts likens digital cameras, cable TV, and the World Wide Web to a “soft and pliable mesh woven from invisible thread” that covers everything. “The so-called natural world,” he writes, “the place we used to live, which served us so long as the yardstick for all measurements can now only be perceived through scrim. Nature was then; this is now.”[21]

The Beginning of Modernity

There are three dates that are generally accepted for the beginning of Modernity: 1517 when Martin Luther began the Protestant Reformation by posting on a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, the Disputation on the Power of Indulgences; 1620; when Francis Bacon secured the scientific revolution on experiment by publishing the Great Instauration; and 1440 when Johannes Gutenberg established the printing press that used reusable moveable type.

Not surprisingly, an artist was a precursor of Modernity. In the early 1480s, Leonardo da Vinci invented modern perspective painting. He claimed, “Painting is based upon perspective which is nothing else but a thorough knowledge of the function of the eye.”[22] By careful examination of vision, he saw that the colors of nearby objects were brighter and sharper than remote objects. To render this insight into a painting, Leonardo invented sfumato, Italian for “smokiness,” the technique of shading an object with transparent layers of oil paint to create smoky shadows, as readily seen in his painting Virgin of the Rocks. Mary has her right arm around the infant St. John the Baptist, who is making a gesture of prayer to the Christ child, who in turn blesses him. Mary’s left hand hovers protectively over her son’s head while an angel looks out and points to St. John. The figures are all in a mystical landscape with rivers that seem to lead nowhere and bizarre rock formations. In the foreground, we see precisely rendered plants and flowers. (See illustration.)

Since the printing press appeared around 1440, the first viewers of The Virgin of the Rocks were mainly illiterates who heard the New Testament read aloud in church and sermons about how Mary and Elizabeth, the mothers of Jesus and John the Baptist, fled with their sons into Egypt. The Virgin of the Rocks illustrates the first meeting of the infants Jesus and John the Baptist in a protected rocky grotto where, amid their flight, they and their mothers have paused to rest. Da Vinci illustrated a story familiar to believers, so they seemed to be present at a biblical event; such presence strengthened their faith.

The Ultimate Question: Who Am I?

Storytelling and personal narratives are universal ways we human beings organize our experiences and interpret the world; we fashion coherent wholes out of sensations, desires, achievements, losses, and experiences with others through stories.

When we tell others who we are, we tell our personal life story, what has made us who we are and what we hope to become. We tell others and ourselves about our successes and failures, our hopes and fears. Our idea of self is a narrative with a beginning, a middle, and an end. We care intensely about our self-narrative and cast our self as the central character, even as the hero, of what we hope is a good story.

We repeatedly tell our personal narrative, adding layer upon layer of meaning, incorporating new experiences into our stories, and perhaps embellishing past events to such a degree that they become fictitious. Just like young children, we develop intense attachments to certain personal stories, revisiting them again and again, for weeks, months, and even years. In this way, our self both solidifies and changes. Consequently, the self is not a static thing or a substance just waiting to be known.

Our personal stories are not entirely of our own making. As infants, we do not enter life as isolated, autonomous individuals, but as members of a family and as participants in the surrounding culture. Psychologist Jerome Bruner concurs: “When we enter human life, it is as if we walk on stage into a play whose enactment is already in progress—a play whose somewhat open plot determines what parts we may play and toward what dénouements we may be heading.”[23]

Around three to five years of age, autobiographical memory emerges, and the development of a unique personal history begins. Even at this young age, the self-narrative that emerges depends upon culture.

When a Harvard undergraduate was asked to think of her earliest memory, she reported, “I have a memory of being at my great aunt and uncle’s house. It was some kind of party; I remember I was wearing my purple-flowered party dress. There was a sort of crib on the floor . . . I don’t know if it was meant for me or for one of my younger cousins, but I crawled into it and lay there on my back. My feet stuck out, but I fit pretty well. I was trying to get the attention of people passing by. I was having fun and feeling slightly mischievous. When I picture the memory, I am lying down in the crib, looking at my party-shoed feet sticking out of the end of the crib.” (Memory dated at 3 years 6 months)[24]

A female Chinese college student from Beijing University described her earliest memory: “I was 5 years old. Dad taught me ancient poems. It was always when he was washing vegetables that he explained a poem to me. It was very moving. I will never forget the poems such as ‘Pi-Ba-Xing,’ one of the poems I learned then.”[25]

Qi Wang and her colleague Jens Brockmeier discovered, after extensive interviews of American and Chinese undergraduates, that the first memories of the Americans were earlier and more focused on the self than those of the Chinese. “The American memory has the individual highlighted as the leading character of the story. In contrast, the Chinese memory shows a heightened sensitivity to information about significant others or about the self in relation to others.”[26]

In America, parents encourage independence, assertiveness, and self-expression. Children are taught to “stick up for their rights” and to believe they can accomplish anything they desire. In contrast, Chinese parents emphasize interdependence, group solidarity, social obligation, and personal humility. Children are taught obedience, proper behavior, emotional restrain, and the value of group harmony.

Memories Are Not Trustworthy

Our life narratives are based on what we think are accurate memories of past events, on the belief that memories are sealed within our skulls, immune from external influence.

Memories not only fade but they are also changed in many ways. The mere telling of an episode of our life narrative to others changes that memory; we enhance those memories that others respond to positively and downplay or edit out those memories that others dislike.

When a young mother shows her child pictures on her cell phone of their trip to Disneyland and says, “Annie, you had such a great time talking to Mickey Mouse; that was the best part of your summer,” she is implanting a memory in her child.[27]

Memories are not like a read-only computer file stored in the brain; remembering is not like retrieving an uncorrupted digital document of our history that is accurately and permanently recorded. Daniel Offer and his colleagues at the Northwestern University Medical School examined “the differences between memories adults had of their teenage years and what they actually said when they were interviewed as adolescents” thirty-four years before. “The subjects’ recollections were about the same as would have been expected by chance . . . the accuracy of recalled memories was uniformly poor.”[28]

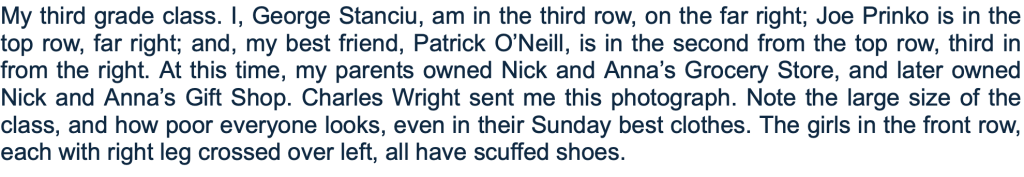

Recently, I received from a childhood friend a photograph of our third-grade class taken in 1944. (See illustration.) I was shocked to see forty-two pupils, for I remembered the class as no more than eighteen students. I recollected that my classmates and I were from the solid middle class; so, I was surprised to see that most of the girls wore homemade dresses and scuffed shoes and that the boys had on well-worn clothes, except for two boys with ties, Joey Prinko and Patrick O’Neill, my two best friends, both of whom I had no difficulty recognizing in the photograph. I immediately recalled that once, when clowning around with them, I broke a bottle I held. I still have scars on my index and middle fingers of my right hand. The memory of this foolish episode has been embellished from years of retelling to myself and others. Yet, the scars, like the childhood scars on my soul, confirm certain events had happened.

Two summers ago, I visited a friend who lives in Provincetown, Massachusetts. When I returned to Santa Fe from Cape Cod, I had vivid, physical memories; I could feel my toes in beach sand, the glaring sun in my eyes, and the smell of the sea breeze. The more I told these memories to myself and my friends, the weaker the concrete memories became, until now they exist only in speech.[29]

With the possible exceptions of wine connoisseurs, painters, and musicians, most of whom maintain that certain things are better left unsaid, verbalization erodes concrete experience until it is replaced by speech.

Our life narratives are based on untrustworthy memories that are a shadow of concrete experience.

We Are Not Our Memories

In Modernity, the self displaces the soul because the basic unit of democracy, capitalism, and the Nation-State is the isolated, autonomous self. Consequently, the discussion of the immortality of the soul by Plato and Aristotle is mainly of historical interest to most of us; we want to know if the self is immortal.

New World Christians proclaim that the self is immortal. When a bereaved self asks a priest or pastor, “Will I see my loved one again?” the answer is invariably “Yes,” with the implication that the desires, habits, and memories of the loved one are either immortal and live on now or will be resurrected in Christ. C.S. Lewis, a New World Christian apologist, even argued (hoped or believed) that his favorite dog would be resurrected with him.[30]

Margaret Guenther, retired director of the Center for Christian Spirituality of the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church, imagines, “Maybe the next life will be a feast for the mind, like great expanses of time in the main reading room in the Library of Congress, only with good lighting and comfortable chairs. Maybe it will be bountiful, like the homecoming picnics at the Martin City Methodist Church, where my father worshiped as a boy.” She confesses, “Sometimes I play with the idea that I will see my grandfather, whom I loved deeply and who died when I was nine, and meet my German grandparents for the first time. . . . Maybe I can have a beer with Meister Eckhart or crochet and chat with Dame Julian of Norwich, while she sews on humble garments, suitable for anchorites.”[31]

Implicit in Guenther’s picture of the next life is her answer to the question, ‘Who am I?” Guenther gives the common answer—I am my memories, a view that does not hold up to scientific or philosophical examination. Neurologist Oliver Sacks reported that a man under his care had suffered a sudden thrombosis in the posterior circulation of the brain, which caused the immediate death of the visual parts of the brain. The patient had lost all visual images and memories yet had no sense of loss. An entire lifetime of visual experience had been erased from memory in an instant.[32]

The visual memories stored in a person’s brain are nonmaterial, but they do not exist separate from his brain; the same is true for all other perceptual memories. My memory of winning the eighth-grade math prize in 1950 at the Middle School in Union Lake, Michigan, will die with my brain, as will my memory of crossing frozen Wilkins Pond during a full moon in mid-winter of the same year. What is true of memory is also true of imagination. My image of myself—a gypsy outsider—will perish with my death. All my acquired emotional habits, such as the fear of dogs and the love of Bach and Mozart, depend upon brain physiology. Even discursive reason, which moves in time, seems perishable.

Through such reflection, my intellect uncovered a terrible truth—my mortality. I then concluded that the mortality of George Stanciu was a calamity that rendered human life meaningless. To ignore or to forget the reality of death, to force this unbearable truth from my mind, I often turned to a sensual life, to amusing diversions, or to other forms of self-narcosis. What kept me from firing a bullet into my brain was that deep down, I thought I had possibly made an error in my analysis of who I am.

The Self: A Cultural Construct

I was not born speaking English or Romanian, nor did I know Newton’s three laws or the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution. I was not born with a self; even when I was two years old, there was no Georgie Stanciu. Child psychologists have observed that around 19 months, a child begins to use the words “my,” “mine,” and “me” and his name with a verb—“Georgie eats.”[33] By 27 months, self-reference is common, although the child is not telling the parents who he is; that requires a narrative. Between three to five years of age, autobiographical memory emerges, and the development of a unique personal history begins.[34] Even at this young age, the self-narrative pattern that emerges depends upon culture.

I was born into a world of complex social relations; others instructed me how to behave and taught me what was important in life; in effect, the world gave me a self, assigned me a unique node in a social web. My parents and relatives taught me that I was part of a Romanian community with indissoluble obligations to others. I can still hear my father telling me that, at times, the other guy needs your help.

At school, the lessons I received contradicted my father’s teaching. In the third grade, I sat at my desk in a row of identical desks; mine was the farthest from the teacher, who sat at a large desk at the front of the classroom. Each one of us occupied a small cubicle with invisible walls. When my best friend, Joey Prinko, reached across the aisle separating our respective rows of desks to hand me a pencil or a crayon, the teacher yelled at him and told him to keep his hands home.

Like every person on the planet, I fashioned my desires, achievements, losses, and experiences with others into a coherent whole through a self-narrative. I called my self into existence, as others did, through language. “George Stanciu” merged the Romanian and American aspects of my childhood into the story “Gypsy Outsider,” a narrative that included bits and pieces taken from literature, pop music, and the big screen. I shamelessly stole the plot of Shane, my favorite boyhood movie. Shane comes from nowhere, has no family or last name, possesses his own moral code, needs no help from anyone, and rescues the cowardly townspeople from the “bad guys,” and then rides off into the sunset. He is the picture of independence, the embodiment of the isolated, autonomous individual.

From early childhood on, I repeatedly told my self-narrative, adding layer upon layer of storytelling, incorporating new experiences into my story, and often embellishing past events to such a degree that they became distorted or even fictitious. I developed intense attachments to certain personal stories, revisiting them again and again, for weeks, months, and even years. In this way, “George Stanciu” both solidified and changed. Hence, a self-narrative is not a reliable history of a person; memories, often invented and usually embellished, are not a person.

Later in life, I realized that “George Stanciu” is an artifact fashioned by culture and personal storytelling, devoid of eternal permanence. Like every isolated, autonomous self, I believed that I was the center of existence to which everything should be ordered and sought to build up myself through the acquisition of knowledge, honor, and love. I laughed when I truly grasped that “George Stanciu” is an illusion, frail and fleeting, with no more permanency than a smoke ring, doomed to disappear into nothingness with the death of his body

A Thought Experiment

I was born in Pontiac, Michigan, and christened George Stanciu, but suppose at two months, the Li family adopted me, and they moved to Beijing, China, their home city. My new family named me Li Zhang Wei. That my given name, Zhang Wei, was second indicated I was first a member of the Li family or clan.

Zhang Wei’s parents emphasized interdependence, group solidarity, social obligation, and personal humility. Zhang Wei was taught obedience, proper behavior, emotional restraint, and the value of group harmony. He understood himself in terms of his relation to a whole, to the Li family, to Chinese society, and, perhaps, to the Tao. “In Confucian human-centered philosophy, man cannot exist alone,” philosopher Hu Shih writes. “All action must be in the form of interaction between man and man.”[35] Zhang Wei always saw himself as part of a larger whole. In the Chinese language, there is no word for “individualism;” the closest word is the one for “selfishness.”[36]

If I were not adopted, my European-American parents often focused on my attributes, preferences, and judgments, making Georgie an individual. Parents in America aim to develop an autonomous self in each of their children and thus encourage independence, assertiveness, and self-expression in their offspring. Georgie was taught to “stick up for his rights and to fight his own battles.”

In grade school, Georgie was trained in the ethos of capitalism. He competed with his fellow students to get the best grades and the most gold stars. In this way, Georgie learned I succeed only if someone else fails, and the converse—if someone else succeeds, I must have failed. Another lesson he learned was that my success is entirely due to me, and no other person has a legitimate claim on its benefits—the fundamental ethic of capitalism, where each person is responsible for their success or failure.

By the end of the sixth grade, Georgie understood himself as an autonomous, isolated individual.

Li Zhang Wei and George Stanciu took their culturally constructed selves to be who they were. While George took himself to be the center of the universe and Zhang Wei did not, both had a natural self-love, although George’s self-love was greatly enhanced by his individualistic culture.

That different cultures produce different “I”s is apparent in the twenty-first century. In America, the “I” is quick to anger; in the Etku Eskimo community, the “I” seldom experiences anger. The American “I” wishes for others to fail and becomes envious when they succeed, while the Lakota “I” takes pleasure in the success of others. In America, the “I” is always lonely; in China, the “I” feels lonely only when separated from a lover or the family. To understand anything, the American “I” first looks to the smallest parts, while the Hopi “I” turns to the whole. The American “I” does not accept any man’s word as proof of anything, while the Japanese “I” seeks guidance from masters. The American “I” demands scientific demonstrations, whereas the Eastern Indian “I” wants a direct experience of the eternal.

In a roundabout way, I arrived at the central insight of the Buddha—the self is an illusion. In the Deer Park at Isiptana, the Buddha preached his second sermon, The Discourse on Not-Self, and “while this discourse was being spoken, the minds of the monks of the group of five were liberated from the taints by non-clinging.”[37]

Arguably, anattā, a Pāli word that literally means no-self, is the most important and most challenging concept in Buddhism since it led the five monks to instant enlightenment, to Nirvāṇa, to “the annihilation of the illusion [of self], of the false idea of self.”[38]

If each one of us were merely a particular compound of body, sense perceptions, memories, and ideas, then no escape from Samsara, the never-ending wheel of birth and death, would not be possible. The Buddha told his disciples, “There is, monks, an unborn, not become, not made, uncompounded . . . therefore an escape can be shown for what is born, has become, is made, is compounded.”[39]

I had no idea what the Buddha meant by the unborn, so I suspected my answer to “Who am I?” missed an essential element of who I am.

In some mysterious way, I was more than my memories, which by themselves without storytelling were disconnected, and more than my self-narrative, whose central plot was my adolescent rebellion against all authority.

The unborn within me, my true self, was a complete mystery, so after stumbling around for years exploring Hinduism and Buddhism, I turned to the most profound understanding of the human person that Christianity offers.

The Patristic Fathers embraced the theological insights of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopogite: God is not any of the names used in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, not God of gods, Holy of holies, Cause of the ages, the still breeze, cloud, and rock.[40]

God is not Mind, Greatness, Power, or Truth in any way we can understand, for He “cannot be understood, words cannot contain him, and no name can hold him. He is not one of the things that are, and he is no thing among things.”[41]

God Is the Unnamable

According to St. Gregory Palamas, we know the energy of God, not His essence: “Not a single created being has or can have any communion with or proximity to the sublime nature [of God]. Thus, if anyone has drawn near to God, he evidently approached Him by means of His energy.”[42]

A person becomes close to God by participating in His energy, “by freely choosing to act well and to conduct [himself] with probity.”[43]

Here, Gregory distinguishes between God’s essence, or substance (ousia), and His activity (energeia) in the world. The energy of God is experienced as Divine Light, such as the light of Mount Tabor or the light that blinded St. Paul on the Road to Damascus.

Given this understanding of God, the image of God within us means that the essence of each one of us is unnamable and that we are known to others only through our activity in the world, that is, through a socially constructed self. We are unknowable to ourselves, although through meditation, or what the Patristic Fathers called contemplation, we can witness our thoughts, memories, and storytelling and thus know that we are not what we witness. Through more advanced contemplation, we may experience Divine Light, the presence of God.

At the core of our being is the unnamable, the “empty mind” of Zen Buddhism, the “pure consciousness” of Hinduism, and the “spirit” of Christianity, although all words ultimately fail to capture our true self. We, the unenlightened, believe that the false self given to us by culture is permanent and fail to see that the false self is an illusion, destined to vanish with the death of the body. Because we take our culturally-given self for our true self, we fail to experience who we truly are. Our true self is always present, completely perfected, with no need for development from us; we must merely step aside. Every spiritual master calls for the death of self and a spiritual rebirth beyond egoistic desires, beyond religious practices, beyond any given culture, beyond the dictates of society, into the law of love, into compassion for every living being.

Suffering

Most of us flee from suffering like the plague. Early childhood traumas, bad relationships that ended with nasty breakups, and conflicts in the workplace, we wish to forget. Most of us believe that if we only forget the one or two memories of terrible events that caused us incredible pain, then we could coast through life free from further trauma. But just a cursory glance at our life shows how misconceived these hopes are. Parents die, siblings fight over inheritance, students refuse to comply with the wisdom of teachers.

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh claims that the Buddha after his enlightenment still suffered; he was nearly assassinated several times, and his old kingdom was invaded and taken over by an evil king. If suffering cannot be eliminated from anyone’s life, then we must in some way learn how to not let it control our lives.

As long as bad memories, or good ones for that matter, have emotions attached to them, they control our lives, and we are not free. Think of an unresolved childhood trauma that causes us to go through our adult lives filled with self-hate. One way of stripping away emotions from a memory is through meditation, which helps us cope with personal problems, especially our monkey minds that jump from one thing to the next and our afflicted emotions. In contrast to Asian Buddhism that aims to leave the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, in modern life meditation is mainly therapeutic. The basic supposition of secular Buddhism is that meditation changes how our minds work, so we can play our various roles—employee, spouse, father, or mother—better, and thus fit into the world in a healthier way.

Another way of eliminating emotions from a memory is through writing, provided the writing is objective, almost as if it belongs to another person. Writing, however, can entrench a memory, if done from anger, bitterness, or despair.

Suffering and Impermanence

The impermanency of all things is indisputable. Civilizations rise and fall; species of plants and animals come and go; continents drift and produce mountain ranges; wind and water erode rock and level mountains. Twentieth-century cosmologists discovered that the universe itself is destined to end with the Big Freeze, a cold eventless state of electrons, neutrinos, antielectrons, and antineutrinos. We are born, walk around for a while, and then disappear. Everything and everyone we love changes inevitably, decays, dies, and vanishes. Nothing lasts. All this is indisputable.

A friend of mine told me, “With my sister, I sat at my father’s bedside as he stopped breathing and tried to understand that he was no longer there, our father. What had become of all he’d known? All that reading of Great Books—sixty years of annotated books, all that was left of a lifetime of thought.” The answer: Gone forever.

The eleventh-century Chinese scholar-poet Su Tung-po compared all human endeavors to the footprints left by geese on snow:

To what can our life on earth be likened?

To a flock of geese,

Alighting on the snow.

Sometimes leaving a trace of their passage.[44]

Most of us desire the impossible, that our loved ones live forever; a denial of impermanence that brings us much suffering. Not one of us will escape losing a loved one to cancer, Alzheimer disease, a car accident, suicide, shooting, a drug overdose, heart attack, or one of hundreds of other ways of dying. Impermanence means that our suffering will not last forever. When we truly grasp the impermanence of everything, we love another and act for their good without being attached to them.

Suffering and Transcendence

Such spiritual masters as Thich Nhat Hanh insist that suffering can produce compassion and love, which seems absurd.

Jesus told his followers, “He who loves his life loses it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life.”[45]

St. Paul confesses, “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me…”[46]

St. Paul’s confession is a mystery to us ordinary mortals; we struggle to understand his straightforward but mysterious description of his new life. Perhaps the best place to begin is with “it is no longer I who lives,” that is with the death of Saul; recall, before St. Paul’s conversion to Christianity, he was Saul, a persecutor of the early disciples of Jesus. On the road to Damascus to persecute Christians, a light flashed about Saul; he fell to the ground and heard a voice, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” Saul was blind for three days; when he recovered his sight, a new person was born, Paul, who became instrumental in explaining Jesus’ message to the world.

We will call the birth of a new person through mystical experience, intellectual insight, or intense suffering Christian enlightenment. For skeptical non-Christians, Homer, in the first great book of Western civilization, gives a precursor of Christian enlightenment.

At the opening of the Iliad, Achilles is angered because Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek expedition to Troy, has taken for himself Briseis, a beautiful and clever woman captured by Achilles. Since Achilles thinks he is the greatest warrior amongst the Greeks, he feels dishonored by Agamemnon, retires to his ship, and refuses to join in the battle against the Trojans. Blinded by his anger, Achilles allows his best friend, Patroclus, to use his armor and do battle against the Trojans. Patroclus, masquerading as Achilles, is killed by Hector, the greatest Trojan warrior. Achilles goes berserk—enters battle, kills every Trojan in sight, including Hector, and in his rage attacks a river, the height of madness.

From Achilles’ immense suffering, a new person emerges. He sees that he has been exactly like other men—foolish, caught up in winning prizes, striving for eternal glory. The new Achilles is compassionate and even smiles at the foibles of his fellow warriors.

Eva Brann, classics scholar and recipient of the National Humanities Medal, is surprised that “with the unaccountable suddenness of a divinity, Achilles is another being: the courtly, peace-keeping, tactful, and generous host at Patroclus’ funeral games.”

The last event of the funeral games for Patroclus is spear throwing. Agamemnon and Meriones step forward to compete for “a far-shadowing spear and [for the first prize] an unfired cauldron with patterns of flowers on it, the worth of an ox.”[47]

The Iliad is about to begin again, this time with Agamemnon taking a prize from Meriones.

Achilles, with newly acquired wisdom, intercedes to stave off an intense conflict between the ruler and the ruled. Achilles tells Agamemnon, “For we know how much you surpass all others; by how much you are greatest for strength among the spear-throwers, therefore take this prize and keep it and go back to your hollow ships; but let us give the spear to the hero Meriones.”[48]

What follows next are the two most remarkable lines in the Iliad. Achilles no longer seeking honor and prizes entreats Agamemnon, “If your own heart would have it this way, for so I invite you [to give the spear to Meriones].” Achilles spoke, “Nor did Agamemnon lord of men disobey him.”[49]

Achilles has become a wise ruler of men.

Homer shows us in the Iliad that suffering can destroy a person’s ego, correct his misunderstanding of himself, and join him in a more profound way to others. Suffering can move a person from narrow self-love to an expansive love of others.

Homer’s insight that we are not determined by fate or culture but can free ourselves from our ill-formed habits and faulty thinking, often through suffering, so as to connect ourselves to others is an essential part of the Western understanding of the human person. For example, James Baldwin, an American, Black writer, citing contemporary experience, agrees with Homer: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who ever had been alive.” The following words of Baldwin could have been spoken by Achilles, “Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people.”[50]

The Western tradition is that from immense suffering, a new person can emerge; such an understanding rests on nature; every human being comes into this world through suffering. A mother in labor experiences intense pain and willingly accepts the risk of death. The fetus, once floating contentedly in amniotic fluid, feels the rhythmic contraction of the uterus and begins the difficult and painful passage through the birth canal to air, light, and a new life.

The image of God within us also means that each of us has the energy to transform the physical and social worlds we inhabit, either for good or evil. For instance, we are free to use the fruits of science for the benefit of life or the destruction of humanity, for creating polio vaccine or thermonuclear weapons, aids for life or instruments of death. Through such free choices, we either draw closer to God or more distant from Him.[51]

Each one of us becomes what we choose.

Our freedom is virtually unlimited; we can thumb our noses at God, refuse to become who we truly are, and embrace a self of our own choosing. However, to freely abandon God, to exist in oneself, and to seek satisfaction in one’s own being is not quite to become a nonentity but is to verge on non-being.[52]

Hell is not the fiery pit of received Christianity, but the complete separation from God—forever. Heaven is not the reuniting with one’s favorite dog, the blissful meeting with one’s unknown relatives, or the pleasure of conversing with the saints, not such “enthusiastic fantasies,” but to “know more deeply the hidden presence by whose gift we truly live.”[53]

The icon The Trinity also called The Hospitality of Abraham by Andrei Rublev appears to suggest that heaven is joining the Holy Trinity in the afterlife. (See illustration.)

Out of habit, we view icons as visual representations of biblical narratives. Given this prejudice, we understand Rublev’s The Holy Trinity as a visual representation of a story from Genesis 18:1-15 called “Abraham and Sarah’s Hospitality.” The biblical narrative begins when “the Lord appeared to [the biblical Patriarch Abraham] by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the door of his tent in the heat of the day.” The three men standing in front of him were angels. When he saw them, he ran from the tent door to meet them and bowed himself to the earth and said, “My lord, if I have found favor in your sight, do not pass by your servant.” Abraham ordered a servant boy to prepare a choice calf and set curds, milk, and the calf before them. He stood by them under a tree as they ate. One of the angels told Abraham that Sarah would soon give birth to a son. Hiding in the tent, Sarah laughed, for she was old, far beyond childbearing. The angel heard her laugh and said, “Is anything too hard for the Lord?”

Later, Christians understood the three angels as the three persons of the Holy Trinity. In The Hospitality of Abraham, the angel to the far left represents God the Father. The angel’s robe is highlighted with brown, blue, and green colors to show the impossibility of rendering God the Father as one image. The angel to the far right, wearing pale green and blue, represents God the Holy Spirit. In iconology, green is associated with the Spirit’s “youth, [and] fullness of powers”[54], and blue symbolizes the everlasting world, the Kingdom of God. The figure of God the Son, the central angel, portrays Christ as Priest, Prophet, and King. Christ holds his hand over the cup of sacrifice; his fingers are bent in the Orthodox sign of blessing and with a bowed head as if saying, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will.”

The Oak of Mamre symbolizes the tree of life and reminds the viewer of Jesus’s death on the cross and his subsequent resurrection, which opened the way to eternal life. The Oak is in the center of the icon above the angel, who represents Jesus. Abraham’s house appears above the angel’s head on the far left. The hint of a mountain on the far right denotes spiritual ascent, which mankind accomplishes with the help of the Holy Spirit.

While all the above is true and helps a devoted believer to reflect on the Trinity and strengthen his prayer life, the most important feature of the icon is the inverted perspective. The angels in the icon are arranged so that the lines of their bodies form a circle. In motionless contemplation, each angel gazes into eternity. Because of the inverted perspective, the focal point of the icon is in front of the painting on the viewer; Rublev is inviting the viewer to engage in an amazing spiritual exercise, to complete the circle of angels, to join in a union with the Holy Trinity, to become a “partaker of divine nature,”[55] a possibility because in Christ, a Divine Person, the human and the divine are joined together in a perfect and indissoluble unity. In Christ, God descended into our midst so we “may have life, and have it abundantly.”[56]

Many Church Fathers were fond of telling their brethren, “God became man, so man might become God.” Made in the image of God means a divine element inheres in every human person, in Jew and Greek, in master and slave, in male and female.

As we repeatedly view the icon and attempt to join the Holy Trinity in contemplation, the trivial, mundane aspects of who we are begins to fade. Some experience the previous suffering of their false self is of no consequence. In freedom, they walk the world serving others.

Like every person, I live in two worlds: the temporal and the eternal. I love the taste of lamb curry, the sound of the cello, the fall foliage of New England, and wonder about the abundant beauty of Nature, where nothing is not beautiful, either to the eye or to the mind. Yet, this physical world, like “George Stanciu,” is transient and eventually vanishes without a trace.

I live among the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak, the ambitious and the lazy, the good and the bad, the loving and the hateful. Grappling with death taught me how to live in this world. I now see that every person I meet in ordinary, daily affairs—the mailman, the bank teller, the butcher at Whole Foods, the obnoxious teenager down the street with his blaring boom box—is part human and part divine, a storytelling self, often confused, dislikable, and in pain, but always transient, and a mysterious self, deathless, an image of God, worthy of unconditional love.

Endnotes:

[1] Sophocles, Antigone, trans. R. C. Jebb, line 614.

[2] Prince Modupe, I Was a Savage (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1957), pp. 53-54.

[3] Standing Bear, p.124.

[4] S. M. Molema, The Bantu: Past and Present (Edinburgh: Green & Son, 1920), p. 136. Italics in the original.

[5] Prince Modupe, I Was a Savage (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1957), p. 110.

[6] See Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966 [1835, 1840]), pp. 429-431

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 544.

[9] Francis Bacon, Great Instauration.

[10] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, (New York: Scribner’s, 1994), p. 3.

[11] Erwin Schrödinger, What is Life? with Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 153.

[12] Steven Jay Gould, a leading evolutionary theorist, reached the same conclusion from a different argument, see Steven Jay Gould, “Humbled by the Genome’s Mysteries,” The New York Times (February 15, 2001).

[13] In Buddhism a flower or a lion is said to be empty, meaning that the flower or the lion has no independent existence separable from everything else; nothing exists in isolation.

[14] R. C. Lewontin, Biology as Ideology: The Doctrine of DNA (New York: Harper, 1992), p. 10.

[15] Ibid., p. 12.

[16] H. Allen Orr, “Awaiting a New Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, 60, No. 2 (February 7, 2013).

[17] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, (New York: Scribner’s, 1994), p. 3.

[18] Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B (2004) 359: 1781.

[19] Richard Dawkins, “Let’s all stop beating Basil’s car.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] Sven Birkerts, The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age (Boston: Farber and Farber, 1994), p. 120.

[22] Martin Kemp ed., Leonardo on painting: An Anthology of Writings by Leonardo da Vinci with a Selection of Documents Relating to His Career as an Artist, trans. Martin Kemp and Margaret Walker (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), p. 22.

[23] Jerome Bruner, Acts of Meaning (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), p. 34.

[24] Qi Wang and Jens Brockmeier, “Autobiographical Remembering as Cultural Practice: Understanding the Interplay between Memory, Self and Culture,” Culture & Psychology (2002) 8:52.

[25] Ibid., pp., 47-48.

[26] Ibid., p. 49.

[27] For a scientific study of implanted memories, see I. E. Hyman Jr. and J. Pentland, “The Role of Mental Imagery in the Creation of False Childhood Memories,” Journal of Memory and Language (1996) 35 (2): 101–17.

[28] Daniel Offer, Marjorie Kaiz, Kenneth L. Howard, and Emily S. Bennett, “The Altering of Reported Experiences,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (June 2000), 39 (6): 735-42.

[29] See Jonathan W. Schooler and Tonya Engstler-Schooler, “Verbal Overshadowing of Visual Memories: Some Things Are Better Left Unsaid,” Cognitive Psychology 22 (1990): 36-71.

[30] C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1962), Ch. 9.

[31] Margaret Guenther, “God’s plan surpasses our best imaginings,” Episcopal Life (July/August 1993).

[32] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (New York: Summit, 1987), p. 39.

[33] Jerome Kagan, Unstable Ideas: Temperament, Cognition, and Self (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 233.

[34] Qi Wang and Jens Brockmeier, “Autobiographical Remembering as Cultural Practice: Understanding the Interplay between Memory, Self and Culture,” Culture & Psychology (2002) 8:52.

[35] Hu Shih, quoted by Ambrose Yeo-chi King, “Kuan-hsi and Network Building: A Sociological Interpretation,” Daedalus, 120 (Spring 1991): 65.

[36] Richard E. Nisbett, The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently . . . and Why (New York, NY: Free Press, 2003), p. 51.

[37] Anatta-lakkhana Sutta: The Discourse on the Not-self in In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon, trans. Bhikkhu Bodhi (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005), p. 342.

[38] Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught, (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. 37.

[39] E. A. Burtt, ed., Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha (New York: New American Library, 1955), p. 113.

[40] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 596A.

[41] Ibid., 872A.

[42] Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[43] Ibid., p. 383.

[44] Su Tung-po, “Remembrance.” Available https://mypoeticside.com/poets/su-tung-po-poems.

[45] John 12:25. RSV

[46] Galatians 2:20. RSV

[47] The Iliad of Homer, trans. Richard Lattimore (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1951), Bk. 23, line 885.

[48] Ibid., Bk. 23, lines 890-893.

[49] Ibid., Bk. 23, lines 894-895.

[50] James Baldwin, quoted by Jane Howard, “Doom and Glory of Knowing Who You Are,” Life Magazine, 54, No. 21 (24 May 1963), p. 89.

[51] See Gregory Palamas, Topics of Natural and Theological Science and on the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts in The Philokalia, Vol. IV, ed. and trans. G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p. 382.

[52] See Augustine, City of God, Bk. 14, Ch. 13.

[53] Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, 2nd ed., trans. Michael Waldstein (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1988), pp. 233-234.

[54] Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons, trans. G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovski (New York, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1999), p. 202.

[55] 2 Peter 1:4. RSV

[56] John 10:10. RSV

The featured image, uploaded by Georges Jansoone (JoJan), is “Vitruvian Man”, illustration in the edition of “De Architectura” by Vitruvius; illustrated edition by Cesare Cesariano, Como, Gottardus da Ponte, 1521 (on exhibition in Brussels). This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of the “Mechanical Brain” is courtesy of Robert Voight, Shutterstock. The “Virgin of the Rocks” (circa 1483) by Leonardo da Vinci is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. “The Trinity” by Andrei Rublev is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News