We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

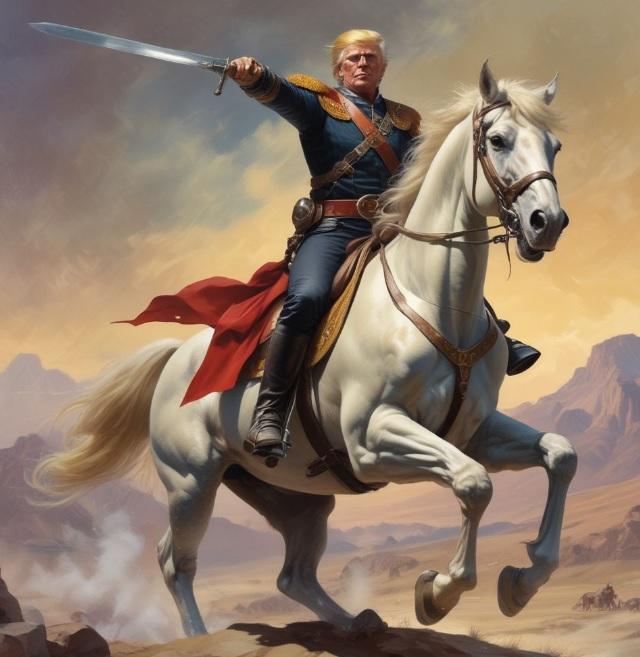

Moments after a bullet shot through his ear, Mr. Trump raised his fist, his face streaked with blood, and charged the stunned crowd, “Fight! Fight! Fight!” Before anyone had triaged how serious his wounds were or concluded the attack was over, Trump wanted to leave his followers with that.

There’s a crisis of leadership in churches because of the expectation forced on pastors that they not fight, that they be doormats; some expect them to be effeminate. After all, two requirements for an elder—including pastors—in 1 Timothy 3:3 are that they not be “strikers” or “contentious.” The first word literally means a “brawler,” prone to fist-fights, the hot-head with a hair-trigger to violence. The second term—contentious—refers to someone who can’t let an opinion he disagrees with go unrebuked, often in the most abusive ways, who continues an argument far past the chance of profitability. Certainly, those are disqualifying faults for a pastor. But think of the kind of person Paul was training for eldership if they had to be warned not to fight over everything, not to hit people they opposed. Does anyone today think your average evangelical pastor needs to be warned not to punch people during his pastoral care? What kind of men were Paul’s churches attracting as shepherds if they had to be warned against taking a swing at their interlocutors? They were fighters. They were men who went into the fray and so needed the wisdom about picking their battles and not to fight in the flesh. But they were definitely fighters.

Pastors are shepherds. Contrary to the stereotype of therapeutic culture which sees shepherds as masseuse of the sheep, shepherds have two main jobs: guide the sheep to where the food and water is, and fight off predators. What are they supposed to do when wolves attack? Fight! Fight! Fight! In Acts 13, Paul’s ministry was being attacked by a wolf, Elymas the magician. Paul, “filled with the Holy Spirit, looked intently at him and said, You son of the devil, you enemy of all righteousness, full of all deceit and villainy, will you not stop making crooked the straight paths of the Lord?” (Acts 13:9-10.) I wonder how many of our genteel pastors today would cluck at Paul for being contentious. Of course, he wasn’t. He was fighting the good fight.

Shepherds fight wolves. Like the Geico ad says, it’s what they do. Certainly, we should do it with “the meekness and gentleness of Christ” (2 Cor. 10:1.) But when a wolf is exposed, we should let the shepherds fight them. He shouldn’t like to fight. That’s being “contentious.” But he should be willing to do it when necessary. Sure, to church members, often through the sermon or in personal counseling, his fighting their spiritual enemies—the world, the flesh, and the devil—should be gentle and courteous, if at all possible. When a shepherd pokes a sheep with his staff, it bleats “bah” and moves along. When he pokes a wolf, it snarls and bites.

The difference between shepherds and sheep in spiritual things is, like in nature, that shepherds fight. So, we shouldn’t hold it against a man if he fights. Maybe he’s not contentious. Maybe he’s a shepherd.

Last Fall, Kevin DeYoung (KDY), pastor of Christ Covenant Church in North Carolina and second-place winner of the 2000 Acton Essay Contest, wrote a scathing criticism of Douglas Wilson of Moscow, Idaho. Wilson likes to playfully portray himself, with videos of him sitting on burning couches or boats as a man at ease with danger. He’s not been shot in the ear and gotten up within seconds and shouted, William Wallace-style, “fight!” But he likes the mood. KDY attacked Wilson’s “Moscow Mood.” I have some quarrels with Wilson, but his mood isn’t one of them. KDY laments Wilson’s bare-knuckle rhetoric. As I described in a recent Theopolis article (“The Tyranny of the Agreeable”), KDY should let Wilson fight.

The therapeutic culture’s antagonism toward a fighting shepherd has vast political implications. The same shepherd-as-masseuse that warps the ministry warps our perception of civil leaders. It tells us to prefer the candidate who “feels our pain” rather than the one who would inflict pain on those who unjustly cause us pain. David French, in “Will Somebody Please Hate My Enemies for Me?”, argues that voting for the man who defied the assassin’s bullet and rallied us to “fight, fight, fight” is rooted in fundamental rebellion against Christ’s command to love our enemies. Political leaders, he seems to believe, are to soothe us with their reassuring platitudes, as many assume pastors are to be. But the truth is that our civil leaders are terrorists for evil-doers (Romans 13:3f). They are God’s servants — whether or not they actually know or acknowledge God — to strike terror into the hearts of criminals, thugs, rioters, punks. So, threatening North Korean dictators that his nuclear button is “much bigger” or sentencing rioters to 10 years in prison is what we should expect of political leaders. French thinks that this is farming out carnal Christians’ hate toward our enemies when in reality it is exactly what leaders are supposed to do. They are supposed to fight.

Mel Gibson’s “The Patriot” portrays a side of paternal role in a searing scene. Gibson’s character is a father who has been trying to avoid conflict during the Revolutionary War when he witnesses one of his sons shot and another, his eldest, taken away to be hanged as a spy. He takes two younger sons with him to ambush the British platoon carrying off the eldest son. The two young sons watch their father nearly single-handedly kill the whole platoon, concluding with him chasing down one last British soldier in the woods, hacking him to death. The two boys are horrified as they see their blood-splattered father emerging out of the woods. They realize he’s dangerous. All their life, he’s been a good and gentle father to them but now they’ve seen that he can fight. Like Liam Neeson’s character in “Taken,” he has a “special set of skills.” So too true leaders—either pastors or presidents—should have a “special set of skills” when it comes to the wolves. They fight, fight, fight.

John B. Carpenter, Ph.D., is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church, in Danville, VA. and the author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church (Wipf and Stock, 2022) and the Covenant Caswell substack. He won the 2000 Acton Essay Contest.

Image generated by AI.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News