We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

What in the twenty-fifth hour might happen to those of us who prefer to live outside the data flow, still analog, still un-captured? Take some time to read “The Twenty-Fifth Hour,” a deep and dark book narrating history prior to World War II. It is for the reader to wonder if the novel resonates today.

I. An Introductory Hypothetical

With millions if not billions of dollars at stake, it’s easy to understand why AI employees hesitate to speak up—at least according to a recent Wall Street Journal article.

Their concerns relate to fears about AI’s threats to humanity and fear of retaliation. Or to introduce a metaphor, what might occur in the Twenty-Fifth Hour.

These are people with the most knowledge as to how AI systems work and believe that the technology could grow out of control. Here’s a quotation: “One of their concerns is that humans could lose control of autonomous AI systems that could in turn make people go extinct.”

Apparently in the race to develop AI systems there are few safeguards and/or little concern for responsibility which is needed for a technology this powerful and so poorly understood.

Turn we then to our hypothetical, which as we all understand, serves as the basis of a suggested idea which may or may not be conjectural unless well-supported by evidence.

I suppose it could become a parlor game or a British television series.

The hypothetical: Have we become addicted to our technology?

A “chatbot” may have an answer or may not have an answer given the “parameters” of the question.

Addicted might also not be the right word unless “dependent” is a synonym or perhaps “compliant.” Thus have we become compliant to our technology?

To use C. Virgil Gheorghiu’s term, the right word is “slaves.” And to broaden the hypothetical is to wonder if we have become so consumed with technology that we have become slaves: Will our cognitive skills diminish?

Please do not call me “Hal” nor critique my nostalgia for my IBM Selectric.

What in the twenty-fifth hour might happen, therefore, to those of us who prefer to live outside the data flow, still analog, still un-captured?

II. Who Is C. Virgil Gheorghiu?

Little known if not forgotten.

I’ve read his The Twenty-Fifth Hour through and believe it scarred by his polemicism. Even so, the aggressiveness is properly directed against Fascism, German National Socialism, and Communism, those three serving their own technological polemics during the 1930s, 1940s and afterwards. Wise to consider Gheorghiu’s novel, then, as his polemic against totalitarianism of all sorts, which makes us “slaves” to various technological forms, which means living without power over one’s life choices.

The “C” stands for Constantin, born in a small Romanian village in 1916. At age twenty he began studying philosophy and theology at the universities of Bucharest and Heidelberg. There’s little in the way of biography except a Wikipedia entry and thus questionable accuracy.

There’s never been an impartial biography with one exception: a French researcher, Thierry Gillyboeuf, whose book has been translated from the French into Romanian, and when the title is translated into English reads, The Man Who Was Traveling Alone. How much is lost with a translation from one language to another and another, well, grist for a linguist.

From reviews I’ve located, Gillyboeuf’s book lacks rigor, owns some interesting photos, but does present an enlarged catalog of Gheorghiu’s publications and their translations. The conclusion is that the book is a flawed piece of scholarship but the author hopes Gheorghiu’s name will be valued and his writings investigated in their real dimension.

I summarize some of what I’ve discovered here:

Early in his adult life Gheorghiu traveled to Saudi Arabia where he learned the language and culture and wrote a biography of Muhammad in Romanian, translated into French, then Persian, Iranian, Urdu, and Pakistani, and there was a rumor the book was to be translated and printed in India.

During the early 1940s, he was an embassy secretary for the Romanian government. When Soviet troops invaded Romania he went into hiding to be arrested by American troops at the end of the war. The reasons for his arrest are unclear, but he wrote The Twenty-Fifth Hour during his captivity and published the novel in French in 1949, with a Romanian translation and then an English translation by Knopf in 1950 by Rita Eldon… the translation I am using here.

In 1963, Gheorghiu was ordained a Romanian Orthodox priest, becoming the Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church in France. He died in 1992 and is interred in the Passy Cemetery.

His obituary references The Twenty-Fifth Hour as his most famous work. The novel was made into a film starring Anthony Quinn. Gheorghiu also wrote Christ in Lebanon and God in Paris. The books are available but not in English.

III. A Brief History of Romania and Hungary

Ask me what I know of Romanian and Hungarian history, and I would have a blank look on my face. I would not know if they have normalized relationships or conflicts. It would take research to discover why there is disagreement about whether Transylvania is part of Romania or Hungary.

It is these days part of Romania, one of its principality regions. Hungarians argue Transylvania was for five hundred years part of the Kingdom of Hungary and that the region is culturally more Hungarian than Romanian. It’s a toss of the coin which language is predominant.

It’s equally complicated when the Transylvania principality was ceded to Romania after World War I. Why that should have been is not clear.

More research reveals that in 1919 Hungary was led by Communists securing its borders, which led to war with Romania, who then occupied the borders.

And more research: Romania was neutral during World War I until 1916 when it was on the side of the Allied Powers only to attack the Kingdom of Hungary. In the next few years two-thirds of Romania was occupied by the Central Powers. [1]

Modern Romania likely began in 1866 when it gained an official state named Romania.

In 1940 as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Romania ceded territory to the Soviet Union and Hungary.[2] Romania entered World War II on the Axis side, warring against the Soviet Union until 1944 when the country switched sides joining the Allies. Following the war, Romania was occupied by the Red Army, becoming a socialist “buffer” satellite, and on the Soviet-influenced side of the Iron Curtain drawn across Eastern Europe.

In 1989, as part of a series of revolutions against the Soviet sphere of influence, Romania gained independence from 42 years of communist rule.

As of this century, Romania is still bound by a communist past; albeit leaders are struggling to define what form Romanian nationalism will take in this post-revolutionary period complicated by inter-ethnic relations. The confusion is the communist educational background and the newer democratic way of ruling the Romanian state.

There are questions with no answers and talks with no ends.

There is also this bit of history: Romania ranks second only to Germany among countries perpetrating the Holocaust, and with an entirely homegrown anti-semitic state enacting legislation which moved from the definition to killings carried out by the Romanian army under the dictatorship of Ion Antonescu. [3] The numbers are staggering, with more than 400,000 Jewish folk perishing from murder, starvation, hypothermia, and disease. Compared to Germany, Romania’s role in the Holocaust is less well known. It’s a sinister chapter in one country’s history and figures in Gheorghiu’s novel.

Both nations are currently members of NATO and the European Union.

IV. The Twenty-Fifth Hour: Transactions on the Road to Technological Slavery?

A proposition first of all:

The important point here is an understanding of technology in its social and historical context, which then assumes that social “engineering” begins by visualizing an interplay between technology and humans and the manner in which humans adapt to technology.

Academic jargon refers to such as “sociotechnical systems theory.” None of which is cause for serious concern unless the technical is privileged over the social, over the human; the consequence is that technology science shapes human thoughts and behavior presumably by opening new possibilities (say for evolution) that gradually or quickly come to be perceived as necessities.

The questions that emerge:

Is there any proof that technology can become a tool of domination rather than liberation? To what degree does technology dominate our every day living? Have we become less sovereign and less self-reflective? Could this dependency be a kind of slavery if technology becomes more and more integrated into our daily lives? If I choose not to adapt myself to technology, am I obsolete?

It’s a dystopian novel and thus denotes an imagined state of affairs where there is great suffering and injustice in a society bereft of reason. Orwell, for example, wrote a novel in 1949 in which British society over a period of time transforms itself into an extreme totalitarian technological society. Add to that a Candide sort of character in The Twenty-Fifth Hour, in as much as things happen to Johann Moritz, while meeting in time the most unbelievable of circumstances, including torture scenes that compare with those of Koestler’s in Darkness At Noon.

On the other hand, perhaps one should qualify: “meeting in time the most believable of circumstances.”

One might also argue, however, that Gheorghiu’s novel is less poetic metaphor and more embedded with his own understanding of Romanian and Hungarian history and an additional “technological” process that reduced a man to an index card in some bureaucratic filing cabinet. To say that the novel resonates with events today is to be mindful of the technological world shaping our world. One reviewer has defined the novel as the story of a simple man told with supreme, if not frightening, realism. And as a point of clarification the novel is not a point-blank luddite grunting, one more argument for chunking television sets out third-story apartment windows. In today’s lexicon the argument would be that such addiction to our technology is a form of slavery which is also political.

What might be different is a novel in which civilization has unwittingly become a slave to technology. The question is whether such a theme is probable or improbable. What was once technologically instrumental has gained incremental superiority, and although it might be a crude exaggeration, “we” have become “slaves” to our technology… and thus an interesting reversal of roles.

V. What Follows the Technological World War III

The concluding sections of this peculiar book are titled “Intermezzo” and “Epilogue.”

The novel presumes the following: every significant war in history is an example of technological advance. In the broadest sense, World War III will become more enabled by technological systems than previous wars.

Consider for a moment the notion that humans are productive about three hours per day. Artificial intelligence operates endlessly without breaks and can “think” much faster than humans and with more accurate results but also more and more advances in automation.

Thus, perhaps, a different kind of warfare.

The two sections mentioned above follow the concluding paragraphs of Book Five, which narrate the decision of the International Tribunal of Nuremberg, representing the voice of fifty-two nations having come together following World War III.

The Tribunal has found that Johann Moritz is a war criminal regardless of what Moritz contends. His health has become precarious and thus his sentence has been reduced to twenty-six years but without hard labor. Instead, Moritz is to be placed in chains and sent on tours through the prisons of the fifty-two nations, spending one month in each country and then starting out all over again.

The penalties have been levied by the Tribunal, representing justice “which is the foundation upon which the Technological Civilization of the West is built.”

It’s a curious title for a legal tribunal which has international authority over all fifty-two nations, made more curious by the argument that Moritz must be kept in first-class preservation. Some countries—Russia, Poland, and Yugoslavia—do not do so with their war criminals. At the commencement of each tour, Moritz is to be carefully weighed and a detailed inventory made of all the parts of his body. Justice requires that “Moritz be kept in good working order,” which is a principle of the Technological Civilization of the West.

Nothing must ever be allowed to deteriorate.

It’s the constitution of the Technological Civilization for the West which considers its mission to civilize the entire globe. “That is our aim and we are proud of it” (377-378).

Perhaps so; but what it means is every individual is no longer free but enslaved to every possible form of technology’s machine-like apparatus.

And which is how the book concludes: the twenty-fifth hour and the time in which “all” become subservient to technology.

VI. Fantana and the Back Story

It’s again an odd book to read, The Twenty-Fifth Hour, and not just because of the title. There are chapters, but within a chapter the reader will find point-of-view transitions into “sub-chapters,” some two or three pages and some less than a page. The effect is an unusual stitching together complicated by occasional lengthy paragraphs.

Such begs the reader’s patience but by pushing through there are rewards.

The first forty or so pages of chapter one are titled “Fantana,” a village in Romania; translated into English that would mean “fountain” or “well.” The pages are interlarded with sub-chapters.

Likely Gheorghiu’s intention is to use the word as a geographical place-setting but also as an allusion to the Fantana Alba massacre on April 1, 1941. Some 3000 folks were murdered in an attempt to cross the Soviet border into Romania near the village of Fantana Alba. The Soviet secret police, the NKVD, tortured and machine-gunned and murdered and buried hundreds in mass graves.

The back story is that in late June 1940 Romania had been forced to cede a large portion of territory and submit to an ultimatum. The sequence of events on both sides of the border became fluid, but many Romanians caught in these events tried to cross the border into Romania, but without permission.

Survivors were labeled traitors and deported to labor camps in Siberia.

The Romanians mark the day as one of tragic memory for the three thousand who walked in a large group carrying three crosses, icons and white flags, while leaving all their possessions behind. It was the twenty-fourth hour for them as they walked and prayed that what would be in front of them would be the twenty-fifth hour of freedom.

For Romanians the day is referred to as the “People’s Golgotha.”

What makes the novel monumental is that Fananta is even to this day a place of sacrifice and that the fountain is a symbol that life springs from sacrifice and that those who lost their lives were not only crossing into Romania but into true freedom in God.

The novel also introduces the reader to a larger context mostly in Books One and Two— the Romanian/Hungarian conflict suggesting a more complex background with contradictory motivations.

What we know of the conflict concerns the interwar period when Hungary moved to the Fascist right and relations with Mussolini and Hitler. The issue for the Hungarians was the earlier loss of territory when Romania gained Transylvania.

During the early years of World War II, then, when the Soviet Union gained more eastern block territory, Hungary escalated its efforts to regain Transylvania.

Ethnic disturbances erupted between Hungary and Romania which led to massacres of Romanians and Jews by Hungarian troops, all taking place in border locations.

More on this in the pages of The Twenty-Fifth Hour.

VII. “Fantana” and “Book One”

Take some time then to read The Twenty-Fifth Hour, a deep and dark book narrating history prior to World War II and then the time in which Romania was hijacked by the Russians. It is for the reader to wonder if the novel resonates today. There are horrors abounding and often difficult to read.

The “Prologue” is again titled “Fantana” and again a village in Romania. The time is the twenty-fourth hour. Susanna and Johann Moritz are standing near a hedge. The stars are bright. They are in love but Johann is preparing to leave. Johann we learn is twenty-five and a native born in Fantana, which has three churches. He’s preparing to leave for America to find work for three years and save money before returning to buy land, a fine property. He’s been working for Father Koruga, who also at one time had been offered a chair in history at a university in Bucharest. He refused preferring stay in Fantana where he celebrated mass on Sundays and holy days.

There’s an irony here when the narrator notes that Father Koruga is prepared to accept what the future holds in store for him. The irony is that America for many is a utopia present in the dreams of the poets but in truth a craving for something that exists only in the imagination.

But the novel makes clear that what the future will hold is different and likely exists only in the darker parts of the imagination.

This first chapter, then, is a pastoral interlude about to be invaded by a darker disturbing element, one of which is Susanna’s father, Jurgu, a brutal man who would scold Susanna when she was small and beat her until he drew blood.

He’s enormous in his physical side and rich and at one time killed a man who had tried to break into his home. He was acquitted, but the killing was more likely than not a simple matter of someone very hungry and in profound need. The villagers were aware. It was a savage murder.

During the time in which Susanna and Johann are together their last night before he leaves, they hear the terrifying sounds of Jurgu beating his wife. Yolanda is screaming, long and drawn out piercing screams, tearing at the very marrow of the bones of anyone nearby who might be listening. Jurgu is stomping her with his boots. It’s a brutal murder.

Johann and Susanna run, during which Johann realizes he will never sail for America. Things are worse when he arrives at his own home where his parents are unwelcoming when they learn there will be no wealth from Susanna. Johann, too, has suffered years of abuse at the hands of his mother. “He was accustomed to harsh words and bullying. His childhood had been one long round of hidings and abuse” (28).

What follows is one of those subchapter scenic shifts in the novel.

Father Koruga is visited by his son Traian who arrives with an old college friend, George Damian, an attorney. Traian has arrived to present his mother and father with his latest novel, his eighth. Traian explains to his father that this novel is going to be a true story and as far as technique is concerned all the characters exist in real life and chosen at random, but exist to symbolize the whole, random characters out of a billion, but what will happen to these characters might well happen equally to anyone else on earth, if not the billions.

It’s a foreboding note and one in which the fiction is closely drawn from the history prior to World War II and then in the years forward where the dystopia deepens.

The plot will, however, involve a crisis from which very few human beings will escape during the next few years.

George Damian wonders what this thing is that Traian alludes to.

He responds that the “thing” is a revolution of inconceivable proportions to which all human beings will fall victim, a technological revolution the centerpiece of which will be World War III, which follows in the time of the novel World War II.

The title to this eighth novel is The Twenty-Fifth Hour and thus a novel within a novel.

The question, however, is when this revolution will break out?

The answer is historically profound inasmuch as the Communists and the Fascists are at that time politically blaming one another for an approaching storm, and to avert the danger are liquidating each other.

And the Nazis wish to save their own skins by killing the Jews.

But when Damian asks whether the revolution is the greatest danger or is there one greater, Traian responds that the greater danger is the process by which human beings will become mechanical slaves, which will begin in the hour that follows the twenty-fourth hour.

Some care must be taken here.

Mechanical does not mean the same as engineering physics. It does mean adaptation, even instinctive behavioral adaptation to changes in everyday life, often without prompting. Physical machines respond to force, but by way of analogy a society can also respond to force and the individuals in that society also respond to force.

The question posed then is such merely a poetic metaphor to be found in novels or true to life?

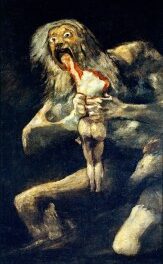

Traian responds by arguing that all one needs to do is self-consciously look around. Who lights the fire in the furnace, heats the house, warms the water for the bath, tills the soil, carries voices over the radio waves and so on and so on. The mechanical slave has mastered every human activity and carried it to perfection. “The mechanical slave has even become executioner carrying out death sentences” (43).

The issue that’s emerging is the process by which Western Civilization has un-consciously adapted the rhythm of the technological age, even to the point in which “persons” are more in technological company than the company of fellow human beings. The numerical superiority is overwhelming, and civilization has become more and more reliant on these robots hovering around us than on God.

Traian goes on to suggest that he can see these mechanical slaves hovering around him, ever in attendance. How many there are becomes the question. The numbers are immense and therefore overwhelming.

But when we realize they hold all the key points in the organization of contemporary society the danger becomes self-evident.

At this point in the narrative the issue enlarges beyond that of a poetic metaphor.

Suppose the mechanical slaves form a proletariat and begin to herd the human race into concentration camps and prisons and liquidating hundreds. What is more than mere theory, according to Traian, is what happens when men are obliged to imitate those mechanical slaves.

To do so is to renounce human qualities and our own laws.

The first symptom of this dehumanization is contempt for the human being, especially when modern man begins to assess by technical standards his own value and that of his fellow man. The only laws are technological laws, and human beings are merely sources for raw energy.

At this point the novel takes on a Kafka-esque mood, answering the questions as to what could happen, which involves wondering whether one could be arrested without cause or whether “we will die in chains” (49).

And the answer is “anything.” And the answer to the second wondering is “yes.”

Here’s a long and polemical quotation.

The moment man has been reduced to the single dimension of his technic-social value, anything may happen. He can be arrested, sent to forced labor, exterminated, made to do any sort of work—for a Five-Year Plan, for the betterment of the race, or for what purpose you will, dictated by the Moloch Technocracy—and all without the slightest regard for his individual aspirations. The Society of Technological Civilization works exclusively according to technological principles, abstractions, and plans, and has only one more precept: production (48).

Noting for the moment, then, that the novel is staged largely before and during World War II: surely the argument could be made that the difference between World War I and World War II is that the latter was much more technologically weaponized. The state of warfare was thus irreversibly altered. It was not bloodless or odorless or soundless, but in recent history when drones were weaponized, warfare became for those distanced pilots much more like a video game than not, and thus no longer close to feel and smell and see; the wreckage human operators have caused would no longer cause them to heave or breathe hard when unleashing blast waves sufficient enough to turn internal organs into jelly.

If such is the inevitable case, Traian argues that mankind is beyond salvation. But there is this one provision, which is that the Technological Civilization cannot create the Spirit. And without the Spirit there is no genius. Thus if Western Civilization is now being superseded by the Technological Civilization, will the downfall of technocracy and the impersonal discipline of the state be followed by a rebirth of human and spiritual values?

In the mean time, listening to his son narrate the theme of his novel, Father Koruga, a deeply spiritual man, sits in silence, his face buried in his hands.

The three men sitting in Father Koruga’s library listened to the cuckoo clock strike one while outside a cold rain drizzled.

And then:

VIII. Father Koruga Prays a W. H. Auden Prayer

“… especially at this time for all who occupy positions of petty and unpopular authority, through whose persons we suffer the impersonal discipline of the state, for all who must inspect and cross-question, for all who issue permits and enforce regulations, that they may not come to regard the written word or the statistical figure as more real than flesh and blood… and deliver us, as private citizens from confusing the office with the man . . . and from forgetting that it is our impatience and indolence, our own abuse and terror of freedom, our own injustice that created the state, to be a punishment and a remedy for sin” (85). [4]

IX. Johann Moritz In Prison

After the Fontana prelude, Book One proper begins with the phrase that two years later the brutal beast Jurgu Jordan was set free from his murder sentence for the death of his wife. It’s unclear why he served only two years of a ten-year sentence for his crime. What we do know is that he is in possession of papers that announce he has become a noncommissioned officer in the SS. He’s a German citizen, and he’s off to do his duty to the Fatherland.

On the letterhead is a crest with swastikas and eagles.

A gendarme has been walking his “beat,” and when he struts down the street we learn that in January he had received an order to assemble all the Jews in the village and dispatch them to labor campos. He passes by Johann’s home, pausing to watch Susanna tread clay to make bricks.

Watching is a good word but lusting is a better word.

His eyes glisten, and his questioning pressure frightens Susanna, and she worries that something evil may be brought down on Johann.

One week later the gendarme delivers a document. It’s a requisition order which explains “what the state wants this time” (61).

As it is, it’s not wheat, or horses or cows, but a “man.” Johann wonders if the order was a mistake because how can the “state” requisition a man?

When Johann does present himself to the offices of the gendarme on this very different twenty-fifth hour, he is placed shoulder-to-shoulder with Marcu Goldenberg, the son of the village Jew whose hands are tied behind his back.

Although not a Jew, Johann has been defined by the gendarme sergeant as a Jew which meant that at age twenty-eight he had fallen into the category “defined by law” which legalized the rounding up and dispatching to labor camps all Jews and suspicious persons.

He persists, however, but when confronted by an adjutant at the camps, the accusations continue, He has a Jewish name and he speaks Yiddish which Johann explains are a few catch phrases he learned while in an earlier camp. But in all the documents he’s listed as a Jew. The documents cannot be wrong, cannot lie.

When he persists the responses he gets are the merciless responses of a machine which in a powerful way requires Johann to accept the unavoidable and thus must live with the unavoidable malice of the gendarme.

The scope of the novel here is true and the episodes adorned with concentration camp horrors and the monstrous regimes of terror and the murder of thousands through the instrumentalities of the machine-like western technological civilization, if that’s the right phrase. If such is true, then not only are Jews caught in the machine trap of technological civilization but so are Gentiles.

Father Koruga begins an investigation only to discover that everything owned by Jewish folks is being requisitioned by the gendarmes followed by life in the streets or the ghettos.

Koruga then visits the office of the “prefecture” to determine what has happened to Johann. He notes that he would like to know where he is and if arrested why he was he arrested. He explains that Johann is a Romanian citizen and a Christian and not guilty of anything.

The “prefecture” responds that he refuses all “appeals on principle.”

Father Koruga questions why he has been put in a Jewish camp when he’s not a Jew.

That makes no difference according to the “prefecture” because so long as he’s in a Jewish camp he comes under special laws and regulations.

Here the point is simply stated by Father Koruga:

“Is it possible that a man should have been brought to such a degree of insensibility that, like a machine, he remains deaf to the voice of his fellow beings?”

Man, however, and according to Koruga, has been created with feelings, with a soul. Man is not a machine or a mechanical slave. But the prefecture is not moved by the injustice done to Johann.

The prefect responds perfectly: “I’m a servant of the state and have no wish to ruin my career. I just keep away” (84).

What’s been established in the novel and in Romanian politics is the alliance with Nazi Germany and with typical figures who become Holocaust perpetrators engaged in ethnic cleansing as servants of the state. As a sort of junior partner to Germany, Romania was also able to preserve a modicum of autonomy. At issue, however, is the resulting regime, the National Legionary State, which became the only legally permitted party, the Iron Guard. Anti-semitic legislation was strengthened and Romanianization of Jewish owned enterprises became the standard influenced by Nuremberg inspired laws.

And as The Twenty-Fifth Hour makes clear, the result became more and more a race war and one in which Antonescu made clear that the national idea would be that of a “new man,” who would be tough and virile and ready to fight for an ethnically pure Romania.

Book One continues with the maneuvering by the Sergeant of the gendarmes in charge of the state police of Fantana who, following the arrest of Johann as a “suspicious person,” sets off to find Susanna alone. When he attempts to open the gate, she threatens to crack his head open with a hatchet.

Meanwhile columns of prisoners are beginning to march off including Johann. An officer hurries by with a pile of papers and addresses the guard yelling “All Yids?” Johann does not understand. The officer grabs him, spins hims around, and gives him a kick that sends him flying into the ranks. Johann falls into step with the other prisoners and vanishes through an open gate.

When the column arrives on the banks of the river Topolitza, the officer explains that the “Jews” were to dig a canal. They’re housed in a stable. They were handed picks and shovels. An adjutant explains by making a speech that for the good and defense of the country the Jews would work or there would be no food. He says that he, the adjutant, “was the God of the Jews and what he said was the law, even for old Moses up in heaven” (72). All for the fatherland.

The work began. Johann approached the adjutant and explained he was not a Jew. The circumstances, however, dictated that Johann must be a Jew even though his name is not Jewish ands he does not always speak Yiddish. They argue that his name must be Jacob.

His time in the camp is four months, during which he continues to argue that he is not a Jew, which leads the adjutant to argue that Johann is an infernal nuisance. He’s examined by a guard to see if he’s been circumcised in the Jewish way; the evidence is unclear. More time passes; the work continues with digging in soft clay. Then the camp moves north, where the digging is through rock and exhausting in the bitter cold.

When Book One nears its conclusion, the reader learns that the racial laws were being applied with more and more severity to the extent that no Jew would be able to elude them.

Ironically, Johann is now the “hero” of Traian’s novel, and the theme is the atmosphere in which contemporary humanity now lives in this Twenty-Fifth Hour: “Bureaucracy, the army, the government, central and local administration, every thing is conspiring to suffocate man. Contemporary society is unsuitable for none but machines and mechanical slaves…. [F]or human beings it is asphyxiating” (122).

Traian has gotten to the end of Book One. Johann has been robbed of his freedom, his wife, his children and his house. He’s been starved and beaten.

Traian is questioned as to who then will be the hero of the second chapter, the Hero of Book Two. He’s also questioned as to whether the following chapters will be like Book One, the story of Johann Moritz.

Will there be one single lucky star, one example of a happy ending?

X. Book Two, Johann Moritz In Hungary

Johann finds himself in a train with two other persons. He’s chided for speaking Romanian because if anyone hears someone speaking Romanian they’ll be locked up. In Hungary, Romanians are put into concentration camps since Hungary considers Romania to be an enemy. Jews, on the other hand, are allowed to speak Yiddish, and there is a Jewish Committee obtaining papers for Jews to go to America with fake passports. Nothing can be done for Johann, who is not a Jew but a Christian and Romanian.

He had been in Hungary for about four weeks when he was caught up in a police road block. He had no papers and with a group was herded in the direction of a truck by police with fixed bayonets. He was under arrest. Four weeks later he finds himself in a cell facing out and into high gray walls that block out the sky.

Book Two continues in detail with his daily beatings. It’s hard to read. Blood coagulates on his mustache and eyebrows, rough and brittle to the touch. His lips are swollen and hurt “like boils about to burst” (134). Four of his front teeth are gone. Time passed, and when footsteps could be heard his thoughts became numb. “The soles of both feet had swollen like fresh loaves” (135). His body had become light as a little child’s; what weight he had once had now come only from his bones.

After days of torture, Johann had reached the limits of his endurance.

But why?

The machine apparatus of the Hungarian secret police did not believe why a Romanian had come to Hungary. Thus he was an “agent” with a subterfuge mission. He explained that he had spent eighteen months in a Jewish camp in Romania. But if he were Romanian he would never have spent time in a Jewish camp. Furthermore, he was trying to pass himself off as a Jew in Hungary. The blows kept coming until Johann was hovering on the outermost verge of life, and then for no particular reason he was released, and being Romanian, sent to a labor camp.

The story continues then with a sub-chapter in which the Hungarian cabinet is discussing the problem of fifty thousand workers. The issue is the political fact that Hungary has become subordinate to the Third Reich but not an ally. Hungary could submit to military occupation or send fifty thousand workers to the Reich for slave labor although the word “slave” is not used. Should those workers, however, be Hungarian? It was decided to send fifty thousand non-Hungarian workers who would be screened to prove that not one of them belonged to a specific foreign power.

Those non-Hungarians are referred to as aliens.

The argument is one in which the ministers believe that a precious balance must be maintained. It’s the second occurrence in which Hungary was required to furnish workers, three hundred thousand on the first occurrence which has now been negotiated down to fifty thousand, a minimum that had to be forthcoming. The debate is between the Premier and the Foreign Ministry.

Germany is in desperate need of man power, a euphemism for slaves. History would understand that this was the manner in which Hungary saved its Magyar blood. [5] History might also regard the decision as noble and worthy and forgive the means employed.

We know it as complicity, and a crime.

In the following sub-chapter, Count Bartholy, chief of the Hungarian press, reflects as follows on the session of the Cabinet:

Anyone who is denied the right to honor and self-respect is a slave…. But nowadays anyone who tries to live a moral life signs his own death warrant. Our society denies a man his personal honor and self-respect, that is to say, his freedom to live. It tolerates him only as he lives as a slave. But this state of things cannot last. A society in which everybody—from a Prime Minister to a street cleaner—is a slave must inevitably collapse, And the quicker it does, the better for all.”

Nevertheless, he publishes the communique from the government with the following addition. The Cabinet has granted special facilities for visas for Hungarian workers who desire to go to Germany to specialize in particular branches of heavy industry.

What’s also underwritten but unknown is that Germany will pay for the workers. After publishing the communique the Count confesses to his son that he has been a party to white slavery, a transition that is the last stage on the road read to moral decadence,

With a flick of his hand, the son asks his father not to worry too much. After all, almost every country in Europe has sold slaves to Germany. Besides, in Society Russia every man is the recognized property of the state. He’s not appalled by this state of affairs.

His son then asks the Count, his father, what time it is since his watch has stopped. His father, the Count, responses, “It is twenty-five o’clock.”

What follows in the next sub-chapter begins as follows:

The foreman of a work crew grins broadly at Johann and says “ [They] sold you to the Germans, old man…. I wonder how much the Hungarians got in return for your hide” (150).

There was even a deed of sale.

Johann and hundreds of others were packed into trains and taken away. There were no lavatory facilities. Outside for a bit of relief, Johann notices a message chalked on every car in German: “Hungarian workers salute their colleagues of the greater German Reich. Hungarians are coming to work for the victory of the axis. Hungarian workers are helping to build the new order in Europe” (151-152).

Cars were decorated with garlands as if for a wedding.

Antim, a railroad car friend with Johann, remarks that “we have all been sold as slaves for life.”

Book Three begins with the note that two years had passed during which Johann was in Germany working in camps and factories, and though suffering, the “officials” showed no signs of emotion. Day by day, the slogan was the same: discipline, obedience, work efficiency. There were some German workers, mostly women, but fraternization was prohibited, and every single movement of the “slaves” was observed.

The point being that “in the German Reich every single one of your movements is observed…. You can do nothing without our being informed at once” (159).

Johann is told that even his very thoughts are being read, which means that if his thoughts turn to what is being produced he and every foreign worker must not know what it being produced, how much, or by what processes.

If a worker attempts to find out, his head will be cut off. A little time ago an Italian worker was executed and a Czech worker is on trial.

A worker is not allowed to think.

The point being again that since a robot can’t adapt itself to man, it’s up to man to adapt movements that coordinate with the machine, which argues that man will have to become a first-class worker.

After five months, Johann no longer thought at all; not even to day-dream.

Midway in Book Three, a Colonel addresses a group of slaves; the subject is how the science of race has progressed rapidly under the National Socialist regime, and for the first time the Colonel plans to publish complete data about the German group, which ethnically bears the name of the Heroic Family (177).

The oddity here is that for a brief moment or so the Colonel places his hands on Johann’s head and declares that Johann belongs to a Germanic group which exists in the Rhine Valley and a group devoted to the racial instinct of self-preservation, the call of the blood, which has safeguarded this group from the sin of intermarriage.

The moment is almost comic as other officers finger Johann’s head and feel his hair while looking upon him with admiration.

The novel continues into Books Four and Five with dialogues between peasants and Father Koruga. The peasants wonder whether the church requires “them” passively to show no resistance while submitting to temporal authority. In this case and with the passage of time the new rulers of Romania are cruel and foreign. The Russians are in the next village.

When the authorities hear that such a discussion has been going on, Father Koruga and the peasants are arrested and condemned, guilty of conspiring against the public safety.

The People’s Tribunal has ordained their execution, and during the night they are taken out and one by one shot in the neck on the edge of a manure pit.

Father Koruga survives and crawls out of the mass-manure grave, which should suggest he will become a survivor and with the testimony of a survivor.

More so, not only are the Russians against the Romanian people, but so are the Americans, who keep numbers of people under arrest for weeks; this during the final weeks of World War II and following.

But why?

In the new Western Technological Society no one is able to register as an individual but as a unity in the category to which that individual belongs. (251).

The novel complicates itself in the remaining Book Five. Johann and Traian are together and Traian is writing The Twenty-Five Hour; Johann doesn’t have enough patience to write his own story.

The subject becomes more frightening with various petitions offered by authorities. The first is an economic subject offered by an economics professor who argues that Western Technological Society is built upon a materialistic basis. Economics is the new Bible. His subject is the lack of fats, a world wide shortage. There are 15,000 persons packed in a camp. He presents a whole series of “facts,” including the argument that every prisoner loses six pounds of fat by transforming them into calories. It’s an enormity of waste since the whole adds up to a monthly waste of forty tons of fat.

It reeks, of course, since there’s no conscience at work, only the economy of rendering prisoners for their fat.

There are more petitions and more internment camps, where interviews take place only to verify data, which when everyone is placed in an appropriate category is mathematic precision at work.

As Book Five begins to conclude, the mood and tone shift. Traian and Father Koruga are together, son and father.

The conversation is whether the whole European continent has become as silent and joyless as the Fantana graveyard.

The conversation concerns the technocrats of the Western Technological Society, who are imposing an aim on life which will annihilate life. Life has become more and more a series of statistics. Everything is reduced to generalities to the point at which mankind has lost all sense of the value of the unique, which takes individual life as the starting point.

It’s inevitable that society should collapse, thrashing about in wild spasms.

Father Koruga then offers the following, a prophecy of sorts:

The rivers of Europe will be flowing with the tears of slaves until even the oceans are overflowing with the bitter tears of men enslaved by science and the state.

God will then take pity on man and a handful of men who have remained human will float on the surface of the waters like Noah in his ark.

Salvation will come but only to men as individuals and will not be granted according to category. Salvation will not come about by logical order which will bring only perdition. The crime of Western Technological Civilization is that it kills the living man, sacrificing him to plans, theories, and abstractions.

There are moments here in which Father Koruga quotes Aquinas and Auden and Cardinal Newman, which brings about a smile of warmth as if a powerful searchlight had been turned on.

Traian and Johann are listening intently to Father Koruga, who then adds that category which is the most barbarous and diabolical imagination ever begotten by the human mind. And let us not forget “that our Enemy himself is a being and not a category” (322).

Traian and Johann understand that Father Koruga is near his end, which is an end illuminated by a smile of warmth and infinite love. His lips were murmuring words, barely audible but Traian thinks he can make out these lines from Cardinal Newman:

I went to sleep; and now I am refreshed.

A strange refreshment for I feel in me

An inexpressive lightness, and a sense

Of freedom, as if I were at length myself,

And ne’er had been before. How still it is.

Traian and Johann proclaim that they will become symbols of protest and that if they die their deaths will be cries of revolt. By doing so they court martyrdom. When Traian, after months in a madhouse concentration camp, walks about with his head up and eyes straight ahead, he nears the wire fence enclosing the camp. It’s unauthorized; no one is allowed within a yard-and-a-half. A Polish guard in the tower with his rifle. Shots ring out. Something warm then flowed over Traian’s hands. He falls and doubles up on the scorching ground by the barbed wire.

In what then is something of a redemptive moment and four days after Traian’s death, Johann receives a letter from Susanna, his wife, from whom there has been no news for nine years. He has hope, and, in still “working good order,” he is eventually released and finds his way back to his wife and children.

The Epilogue is Gheorghiu’s last polemic but with World War III raging in Europe. The camps are filled to overflowing. The only way out is the blot out any last hope. The only way out is to volunteer and behave according to technical laws, like machines and become transformed into a “citizen” who no longer has anything in common with the conception of a human being.

No longer….

Notes:

[1] Central Powers is a term used to describe the military alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.

[2] Also known as the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939. Part of the Pact, the secret protocol, portioned Central and Eastern Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union but came known only during the Nuremberg trials.

[3] Antonescu was a Romanian military officer who became a wartime dictator facilitating the Romanian Holocaust by entering into an alliance with Nazi Germany and thus responsible for decimating the Romanian Jewish population. He was tried for war crimes and executed in 1946.

[4] See W. H. Auden, “Selected Poems.”

[5] In Hungarian history there were at one time seven tribes or family clans. Came a time in which the “chiefs” of these tribes organized into a single “blood brotherhood and through sworn allegiance became one nation, Hungary. We know, however, that Hungary/Magyar, is geographically at an exposed European crossroad which has led to invasions but also times in which the country expanded its territory and then contracted also over the centuries. One such contraction came from Austria in the 17th century which led to a Germanizing influence which likely led to a concern for a pure Magyar gene pool as opposed to mixing with other ethnic groups including Jews whose population was almost completely “eliminated” during World War II.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay. The image of Constantin Virgil Gheorghiu is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News