We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

According to Tocqueville, a new political science must account for both the immediate and the universal, the moment and the eternal. When we fail to understand the choice that God has given us with democracy—that is, a science to guide, attenuate, and hone democracy—the baser instincts will rise to the fore.

Tocqueville breaks his own introduction to volume one of Democracy of America into two distinct parts. The first part explains that democracy has taken the place of Christianity—or is on the verge of doing so—as a messianic ideology that permeates and re-creates all that it touches. Nothing, it seems, can be immune from its influence and pervasion. Following closely from this, Tocqueville writes the second part of the introduction as an exploration of what a “new political science” would need to take into account. As he explains:

To instruct democracy, to revive its beliefs if possible, to purify its mores, to regulate its movements, to substitute little by little the science of public affairs for its inexperience, knowledge of its true interests for its blind instincts; to adapt its government to times and places; to modify it according to circumstances and men; such is the first of duties imposed today on those who lead society. A new political science is needed for a world entirely new.

It would be easy, Tocqueville warns, to focus on a particular moment, event, or person, mistaking it for the whole. A new political science, however, must account for both the immediate and the universal, the moment and the eternal.

When we fail to understand the choice that God has given us with democracy—that is, a science to guide, attenuate, and hone democracy—the baser instincts will rise to the fore. “So democracy has been abandoned to its wild instincts; it has grown up like those children, deprived of paternal care, who raise themselves in the streets of our cities, and who know society only by its vices and miseries. We still seemed unaware of its existence, when it took hold of power without warning.”

As such, democracy, thus far, has grown wild and licentious, on the verge of untamable. Though this process is stoppable and alterable, it will take some doing to make it work. As of the 1830s, Tocqueville fears, the material changes of democracy had far outpaced any of the spiritual restraints, customs, traditions, norms, and mores that make a thing good and acceptable, especially when dealing with a way of life. Many critics, understandably, thus see only the ills that democracy brings, failing to note its higher qualities. Habits, especially, have shown throughout history, the propensity to limit the ills of a thing, to make it acceptable to a population and to the stability of society.

Here, Tocqueville first argues for the sanctity (or the necessity of the sanctity) of voluntary and natural associations in rising democracies, especially with the loss of formal and landed aristocracy. “Instructed in their true interests, the people would understand that, in order to take advantage of the good things of society, you must submit to its burdens,” Tocqueville claims. “The free association of citizens would then be able to replace the individual power of the nobles, and the State would be sheltered from tyranny and from license.” This will prove as true in France as it does in America. The circumstances are different in the two societies, but not unrelatable, one to the other. In France, the people had thrown off the tyranny of monarchy, but they had replaced it only with quiescence, not with confidence. “The prestige of royal power has vanished, without being replaced by the majesty of laws; today the people scorn authority, but they fear it, and fear extracts more from them than respect and love formerly yielded,” he proclaims. Therefore, “society is tranquil, not because it is conscious of its strength and its well-being, but on the contrary because it believes itself weak and frail; it is afraid of dying by making an effort.”

France, consequently, suffers from bizarre and manifest disorders.

Hindered in its march or abandoned without support to its disorderly passions, democracy in France has overturned everything that it met on its way, weakening what it did not destroy. You did not see it take hold of society little by little in order to establish its dominion peacefully; it has not ceased to march amid the disorders and the agitation of battle. Animated by the heat of the struggle, pushed beyond the natural limits of his opinion by the opinions and excesses of his adversaries, each person loses sight of the very object of his pursuits and uses a language that corresponds badly to his true sentiments and to his secret instincts. From that results the strange confusion that we are forced to witness. I search my memory in vain; I find nothing that deserves to excite more distress and more pity than what is happening before our eyes; it seems that today we have broken the natural bond that unites opinions to tastes and actions to beliefs; the sympathy that has been observed in all times between the sentiments and the ideas of men seems to be destroyed, and you would say that all the laws of moral analogy are abolished.

Yet, Tocqueville reminds the reader, no one should despair at this disorder, but it is merely a misunderstanding and poor management of God’s gifts and God’s demands. After all, God had previously introduced equality in the world, but then He did so only through the Christian religion. Now, however, God is introducing equality into the material and the political realms.

America, counter France, was chosen (by the Divine) to demonstrate to the world that equality could work in religion, in material progress, and in political society.

Past centuries saw base and venal souls advocate slavery, while independent spirits and generous hearts struggled without hope to save human liberty. But today you often meet men naturally noble and proud whose opinions are in direct opposition to their tastes, and who speak in praise of the servility and baseness that they have never known for themselves. There are others, in contrast, who speak of liberty as if they could feel what is holy and great in it and who loudly claim on behalf of humanity rights that they have always disregarded.

Yet, even in America, there is confusion, especially regarding equality and democracy.

I notice virtuous and peaceful men placed naturally by their pure morals, tranquil habits, prosperity and enlightenment at the head of the populations that surround them. Full of a sincere love of country, they are ready to make great sacrifices for it. Civilization, however, often finds them to be adversaries; they confuse its abuses with its benefits, and in their minds the idea of evil is indissolubly united with the idea of the new [and they seem to want to establish a monstrous bond between virtue, misery and ignorance so that all three may be struck with the same blow].

Yet again, Tocqueville reminds his audience, God chose America to bear witness to His emerging truths.

Will I think that the Creator made man in order to leave him to struggle endlessly amid the intellectual miseries that surround us? I cannot believe it; God is preparing for European societies a future more settled and more calm; I do not know his plans, but I will not cease to believe in them because I cannot fathom them, and I will prefer to doubt my knowledge than his justice.

Tocqueville finds evidence in his claims—beyond mere assertion—in the history of America. As early as the beginning of the seventeenth century, colonists had gone alone into the wilderness, creating their own communities in relative freedom and isolation, not controlled by the habits of the mother country. “There”—that is, in North America—”it was able to grow in liberty and, moving ahead with mores, to develop peacefully in the laws.” In experience, the Americans discovered that democratic governments could take shape in a variety of ways and forms, recognizing that though God was absolute, His will could be satisfied in many different ways and modes of life and government.

Powerfully, Tocqueville concludes his introduction by admitting that he saw more in America than merely America. “I admit that in America I saw more than America; I sought there an image of democracy itself, its tendencies, its character, its prejudices, its passions; I wanted to know democracy, if only to know at least what we must hope or fear from it.”

America, it seems, was not just a place of the past. It was the future made manifest in the present.

This essay is the second in a series on Alexis de Tocqueville. The first may be found here.

This essay was first published here in September 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

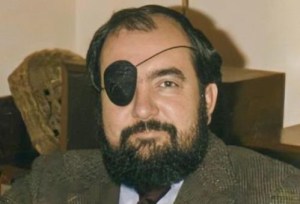

The featured image is a portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville (1850) by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News