We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Poetry and prayer provide something artificial intelligence can never produce—the vital connection between the reality of the physical world and the greater reality of the unseen world. A poem, like a prayer, is the human soul reaching out with words to the wordless.

Our middle son explained how artificial intelligence could help him work as a nurse: “I can ask AI to devise a diet, exercise, and health plan for a particular patient, and it will come up with a complete diagnosis, diet, exercise, and overall health lifestyle plan in a few seconds.” Our oldest son explained how he’s using AI to help his business with insurance and finance correspondence. “A machine opens the letters and feeds them into a scanner which reads the letters—even handwritten ones—then AI devises a proper response, prints out the letter, or writes an email and sends it.”

All very wonderful I’m sure, and not wishing to be too Amish or Luddite about it, I can see the practical applications of artificial intelligence. Indeed, the whole concept is based on a perception of reality that is wholly utilitarian. If you can do it smarter and faster and without error you save time and money, and that must always be a good thing right?

Yes, well maybe, but there are more things in heaven and earth Horatio than your utilitarianism hath dreamt of. Things like prayer and poetry and art and music and being a living soul.

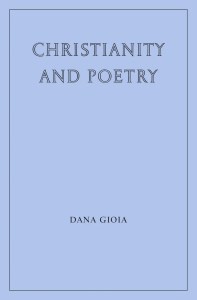

These conversations took with my sons took place while I was contemplating an essay by the poet Dana Gioia titled Christianity and Poetry. Gioia sets out his premise in the first page: “Most Christians misunderstand the relationship of poetry to their faith…. Poetry is not merely important to Christianity. It is an essential, inextricable, and necessary aspect of religious faith and practice.” He goes on through his essay to meditate on the theological significance of poetry and traces the essence of poetry through the Scriptures before going on to provide a handy summary of the history of Christian poetry in English.

These conversations took with my sons took place while I was contemplating an essay by the poet Dana Gioia titled Christianity and Poetry. Gioia sets out his premise in the first page: “Most Christians misunderstand the relationship of poetry to their faith…. Poetry is not merely important to Christianity. It is an essential, inextricable, and necessary aspect of religious faith and practice.” He goes on through his essay to meditate on the theological significance of poetry and traces the essence of poetry through the Scriptures before going on to provide a handy summary of the history of Christian poetry in English.

Gioia’s second chapter is most important. There he explores the poetic heart of Christianity itself: the incarnation. It is no mistake that the miracle of the incarnation is proclaimed by the Virgin Mary’s poem of praise, the Magnificat. If poetry is the metaphorical expression of metaphysical truths, then the incarnation is itself a poem. Christ is God’s poem to humanity, if you like. With poetry at the heart of Christianity, it is arguable that a Christianity without poetry is not Christianity at all, but a collection of dull dogmas, rules, regulations, rubrics, devotions, and doctrines.

Gioia’s basic premise is that poetry is like prayer. The poetic ability lies at the heart of humanity as the religious instinct, and to extend his premise, poetry and prayer are what make humanity unique. An ape can be taught sign language, but he cannot write a poem. A gorilla can mimic human gestures and emotions, but he does not pray.

Which brings me back to artificial intelligence. An enthusiastic friend tells me that AI can write a poem and write a prayer. No it doesn’t. Artificial intelligence mimics a poem and a prayer. Artificial intelligence apes poetry and prayer. No matter how impressive the imitation, it remains artificial intelligence. When we were building our new church, the question arose as to whether we should have a pipe organ or purchase a less expensive, but very good, electronic instrument. The salesman for the electronic instrument explained how they had recorded real pipe organ sounds and the computer and audio system reproduced them to replicate a real pipe organ. The salesman of the pipe organ company said to me, “Yes, all very impressive and definitely less expensive, but let me ask: Would you buy your fiancee a zirconium ring?” The same reasoning disallows recorded music, silk flowers, and cheap reproductions of sacred art in our church. There’s enough fakery, fraud, and foolishness in religion, so when it comes to poetry and prayer let’s have real, not artificial, intelligence.

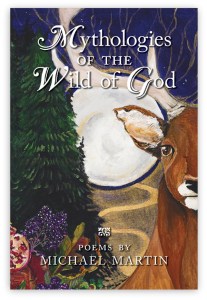

Along with Gioia’s important book on poetry, two volumes of real poetry have been on my ‘books to read and review’ pile for some weeks. Mythologies of the Wild of God is a new collection of verse by Michael Martin. Martin is a farmer, a philosopher, a father, and a musician. His poems are rooted in his life in the countryside, and in our increasingly artificial life, they resonate with a reality that is refreshing. These are poems with blood on their hands—they reek of the guts and glory of farmland—the worms of woodland, wild beasts, meadows, livestock, hunts, and hard labor. Envision Robert Frost filtered through Cormac McCarthy.

Along with Gioia’s important book on poetry, two volumes of real poetry have been on my ‘books to read and review’ pile for some weeks. Mythologies of the Wild of God is a new collection of verse by Michael Martin. Martin is a farmer, a philosopher, a father, and a musician. His poems are rooted in his life in the countryside, and in our increasingly artificial life, they resonate with a reality that is refreshing. These are poems with blood on their hands—they reek of the guts and glory of farmland—the worms of woodland, wild beasts, meadows, livestock, hunts, and hard labor. Envision Robert Frost filtered through Cormac McCarthy.

Within the earthy musk of these poems there simmer sexuality, sensuality, and spirituality. Martin is deeply, physically, spiritually Catholic, and his poems wrestle with his masculinity, humanity, and reality. They surge with a surprising, stunning insights and enlighten with new perspectives. They meld poetry and prayer together just as they should—modern, intimate, powerful, and personal. I will come back to Michael Martin’s poems because they remind me of a gutsy and gritty reality that I have lost in this gasping, gurning, gargoyle world.

The second volume of verse from Angelico Press is Untimely Lightenings by English poet Anna Rist. Redolent of English places, people and customs, I was reminded of the frail femininity and faith of Elizabeth Jennings combined with the wonderful wordplay and scintillating complexity of Hopkins. Rist writes of marriage and family and fond memories, of Italy, England, Catholicism’s calendar and the memorials of saints. There is at once a fragility and robustness in these poems. I sense one of those solid, sensible and yet sensitive English women who capture the best of English letters and language with intelligence, learning and the wisdom of age.

The second volume of verse from Angelico Press is Untimely Lightenings by English poet Anna Rist. Redolent of English places, people and customs, I was reminded of the frail femininity and faith of Elizabeth Jennings combined with the wonderful wordplay and scintillating complexity of Hopkins. Rist writes of marriage and family and fond memories, of Italy, England, Catholicism’s calendar and the memorials of saints. There is at once a fragility and robustness in these poems. I sense one of those solid, sensible and yet sensitive English women who capture the best of English letters and language with intelligence, learning and the wisdom of age.

Both Anne Rist and Michael Martin reveal in their own deeply personal verse that poetry is partly prayer and prayer partly poetry. They also reveal, in this plastic and impersonal age, that poetry and prayer provide something artificial intelligence can never produce—the vital connection between the reality of the physical world and the greater reality of the unseen world. A poem, like a prayer, is the human soul reaching out with words to the wordless. Each in their own way, these poems are expressions of the human heart, touching the untouchable and glimpsing for a moment the expanse of eternity.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News