We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

No survey of contemporary literature can call itself complete today which ignores Catholic literature. And this not only because of the promise it holds out for a complete renovation of the arts, but also because of its many distinguished writers and its not inconsiderable critical and creative work in all departments of literature.

The Catholic Literary Revival, by Calvert Alexander, S.J. (368 pages, Cluny Media)

The history of the Catholic Revival during the past three or four generations presents a number of sharp contrasts such as this, which to those who have not followed its development must seem almost unbearably abrupt. Dean Inge, for instance, announced several years ago, with the air of one who had discovered a plot, that instead of the contempt felt for the Roman Church in England a hundred years ago, it was now “the fashion for popular men of letters to become Romanists.” What he had in mind was not the conversion of the poet, Alfred Noyes, or that of the novelist, Sheila Kaye-Smith, which occurred about this time, but the rather long list of writers who since the beginning of the World War have come into the Church, including Compton Mackenzie, Ronald Knox, Christopher Dawson, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, Christopher Hollis, Bruce Marshall, Evan Morgan, Francis Stuart, Algernon Cecil, together with disquieting rumors of others. This, however, had not seemed anything worthy of remark until the advent of the centenary of the Oxford Movement caused him to catch the contrast between this state of affairs and that which prevailed in 1833.

These contrasts are particularly startling and inexplicable to those who have got into the habit of thinking of the world and of the Church in terms of the nineteenth century. Such contemporary phenomena as the blasphemies everywhere being hurled at that Liberalism against which the early Catholic revivalists rebelled, the popularity of Thomistic philosophy among intellectuals, the respect in which pagan litterateurs hold the mystical wisdom of St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross; the spectacle of an ecclesiastic like Martin D’Arcy being looked up to as an important philosophical leader, of a man with so outstanding an evangelical name as Knox, now a Catholic priest and one of England’s first satirists, of a radical exponent of modern art like Eric Gill laying down a Catholic aesthetic, of Christopher Dawson’s importance as a critic of culture—all these and numerous other phenomena which are a part of the modern scene are, according to the philosophy of the man in question, things that should not have happened, and since they have happened, must be a temporary something or other, appearing from nowhere and likely at any moment to go back there—a fashion.

According to this philosophy, for instance, it was inevitable that the world should go on developing along the lines laid down for it by Thomas Huxley in England and by Ernest Renan in France. Today, however, the grandson of Thomas Huxley, Aldous Huxley, is found damning his grandparent’s dialectic in terms much stronger than those used by any of the nineteenth century popes; while in France the grandson of Ernest Renan, Ernest Psichari, killed in the World War after his conversion to the Church and whole-hearted repudiation of everything his grandfather stood for, has become the symbol of a Catholic intellectual and literary revival that has given to France its most outstanding modern novelists, critics, poets, and philosophers.

It is not only non-Catholics, but Catholics too, who are not infrequently surprised when they discover many distinguished modern authors not only professing Catholicism but writing under the influence of the full spirit of the Church. They are surprised because they also have been accustomed to think of the Church as it existed in the nineteenth century, when, as Paul Claudel has said, “by losing its envelop of Art…it became like a man stripped of his clothes; in other words, that sacred body, composed of men, believers and sinners alike, displayed itself for the first time materially before the eyes of the world in all its nakedness, in a kind of exhibitionism and permanent translation of the wounds and infirmities.” Those were the days of the great schism between the artist and Catholicism when it seemed that art and sanctity must be forever separated. One thinks of the convert J. K. Huysmans standing among the crowd of pious pilgrims at Lourdes, his soul harassed by the observation that, although Mary had chased the devil from the rocks of the shrine and the hearts of the pilgrims, he was still there blaspheming her and her Son by the “hideous” architecture of the place. He distinctly hears the devil say to Mary: “I shall dog your footsteps, and wherever you stop, there I shall establish myself; you may have at Lourdes all the priests you please, but art, which is the only worthwhile thing on earth after sanctity, not only will you not have, but I shall so effect that it will unceasingly insult you by the prolonged blasphemy of its ugliness… All that represents you and your Son will be grotesque.…”

Catholics have come to look upon bad art almost as one of the “notes” of the Church by which men might know that she was of Christ—a kingdom not of this world. In many ways this was not a situation wholly to be deplored. For one thing it was a guarantee that those who did come to her then, came because they placed a higher value on the supernatural life than upon their art. To the nineteenth-century convert it seemed that he was making a disjunctive choice between art and religion, and having chosen the new supernatural life on this basis, his art also was renewed. But he was surprised that this should be so. “You thought you were giving up poetry, Giovanni!” exclaimed the Danish writer, Johannes Jörgensen, after his conversion at La Rocca. “Behold, she is coming to you and she is fairer than ever before.” Today, however, it is impossible for an author to think there can be any conflict between his Catholicism and his art. Indeed there is some danger that he may make his art the chief reason for becoming a Catholic.

The intellectual and artistic position of the Catholic Church today—stronger, it is asserted, than at any time since the Middle Ages—is a fact that no one denies, although one does find at times the rather subtle effort to explain it away by regarding this resurgence as a phenomenon of great suddenness sprung unexpectedly and full-armed out of a chaotic situation from which anything bizarre might be expected. The exponents of this view, it is significant, invariably take the same attitude toward the collapse of the “old world of modern history”; they were given no warning; the firmament of the old values suddenly came rattling down about their ears. But, as a matter of fact, neither of these events came about unexpectedly. They were both a matter of slow and certain evolution. Anyone familiar with the events that were taking place within the Church during the last half of the nineteenth century could not have failed to notice the awakening and consolidation of forces that were bound to make their internal position more powerful with the years. So, too, one has only to read the history and the literature of the world outside the Church during the same period to perceive the inevitable operation of an opposite process, the languishing of spiritual energies, the deep down decay of the props upon which the huge apparatus of material culture rested, the sense of uneasiness, revolt, and frustration that gripped men’s minds. Such a world was bound to decrease because its inner life was withering; and in proportion as it did decrease, in proportion as it lost its ascendency over the best intelligences, the allegiance of these intellects would be given to the Catholic Church, not only because of the increased life of the latter, but because of the very different sort of culture for which it stood. Complete loss of faith in the old secular world would mean a renewed faith in the new supernatural world. It would either mean that or abysmal despair. So true was this that a wise nineteenth-century man could have predicted with accuracy that when the consciousness of the old world’s death became widespread, equally widespread would be the turning of men to Catholicism.

The intellectual and artistic position of the Catholic Church today—stronger, it is asserted, than at any time since the Middle Ages—is a fact that no one denies, although one does find at times the rather subtle effort to explain it away by regarding this resurgence as a phenomenon of great suddenness sprung unexpectedly and full-armed out of a chaotic situation from which anything bizarre might be expected. The exponents of this view, it is significant, invariably take the same attitude toward the collapse of the “old world of modern history”; they were given no warning; the firmament of the old values suddenly came rattling down about their ears. But, as a matter of fact, neither of these events came about unexpectedly. They were both a matter of slow and certain evolution. Anyone familiar with the events that were taking place within the Church during the last half of the nineteenth century could not have failed to notice the awakening and consolidation of forces that were bound to make their internal position more powerful with the years. So, too, one has only to read the history and the literature of the world outside the Church during the same period to perceive the inevitable operation of an opposite process, the languishing of spiritual energies, the deep down decay of the props upon which the huge apparatus of material culture rested, the sense of uneasiness, revolt, and frustration that gripped men’s minds. Such a world was bound to decrease because its inner life was withering; and in proportion as it did decrease, in proportion as it lost its ascendency over the best intelligences, the allegiance of these intellects would be given to the Catholic Church, not only because of the increased life of the latter, but because of the very different sort of culture for which it stood. Complete loss of faith in the old secular world would mean a renewed faith in the new supernatural world. It would either mean that or abysmal despair. So true was this that a wise nineteenth-century man could have predicted with accuracy that when the consciousness of the old world’s death became widespread, equally widespread would be the turning of men to Catholicism.

This process becomes quite apparent when one examines the nature of the “old world” in which men have ceased today to believe. The philosophers and critics of culture are virtually unanimous in designating it as the world that began at the Renaissance. It was a humanistic world, a world with a splendid confidence in the autonomous natural man and in the ability of his spirit to rule and enrich the earth. The culture which the Renaissance had inherited and from which it separated itself had been built upon a different principle. It was humanistic, but its humanism was that of the Christ-man and not of the natural man. It was a supernatural culture; it drew its strength from and founded its achievement on the fact of the Redemption. Yet it was also, as Étienne Gilson remarks, “the heir of Athens no less than of Bethlehem and of Rome, Western thought in its most complete form,” determined to sacrifice nothing that might give the supernatural man of the Redemption, “more truth, more beauty, more love and order.”

It may seem too simple a statement of the project of post-Renaissance history to say, with Berdyaev, that it attempted to carry forward this culture without its supernatural foundation; that in breaking with this energizing source its career has been one of extravagant spending in which the natural man has squandered the cultural capital accumulated by the supernatural man, and that he has at length climbed to the summit of the modern period weak and exhausted, stripped of his own and the cultural capital he originally inherited. Yet it is a good general statement of what has happened. Progressively, if not all at once, the society of the modern world has come to be one built upon the natural man, and its failure is unmistakably the failure of that natural man.

Man, says Aldous Huxley, has sunk toward a kind of “subhumanity,” and his advice is that we try to live “superhumanly.” Gorham Munson, the American critic, after rejecting as inadequate the program of the American Humanists to revive a dying world by a return to the well-springs of the Renaissance, opines that the situation would seem to call for nothing less than “a science for divinizing man.” “For here is man, the prey of innumerable illusions, stunted in psychological growth, spiritually inert, bewildered by himself, discordant in behavior, perhaps incurably paralyzed in will. Will anything but the tremendous means metamorphose him into a falconer of reality, an experiencer of bliss and ecstasy, a doer of deeds on the fighting edge of the cosmos?”

Some may choose to see in the rather general feeling we find around us today that one cultural order has perished and man is in labor until another shall be born, merely a recurrence of what took place in the early Romantic years of the nineteenth century, or what occurred again and with greater violence in the closing years of the same century. But there is an essential difference between these periods of disillusionment and our own which must not be overlooked. The blasé, skeptical citizen of the 1890s, for instance, had lost faith in Victorian civilization but not in the natural man that had produced that civilization. He still believed in him; and the numerous renaissantial movements on which he squandered his enthusiasm all postulated a naïve belief in that lay creature, and in his inherent powers of recovery and expansion. But the thoroughgoing skeptic of our own day has lost his faith not in any particular culture or civilization, but in man himself, in the natural man which Europe for the last four centuries has worshiped. The culture of the modern world is decadent because that man is dead. Its renovation demands nothing less than that “tremendous means” of man’s rebirth. He must be born again.

“How can these things be done?” This question put by Nicodemus to Christ in a famous midnight interview of long ago has become a modern question. And Christ’s answer to it is a modern answer. Yet all do not accept it. There is something terrifying in the radicalism of this Christian rebirth. It seems almost too “tremendous a means”; it demands the abandonment of so many familiar ideas, conventional ways of acting, and uncritical beliefs which are, for all that, nonetheless dear to one.

Yet many have accepted it, and this is especially true of modern artists and writers. It is they who constitute modern Catholic letters. I speak here not only of converts to Catholicism but of converts from a certain type of bourgeois Catholicism which has been willing out of an absurd deference to a prosperous humanistic world to deprecate the supernatural content of their faith. Yes, Catholic literature is entirely a literature of converts. It is written from a new aesthetic based on a new concept of man. One does not hesitate to call the genuine Christian today a novus homo. In a world which for centuries has known only the natural man or a weak parody on the Christian one, the truths of Christ’s redemption and elevation of human nature have all the newness and freshness they had to the man of the old Roman world. These truths are new in an absolute sense, too; for man is older than the Redemption, and it is only through Christ that anything that might be called new has entered into this very old world.

No survey of contemporary literature can call itself complete today which ignores Catholic literature. And this not only because of the promise it holds out for a complete renovation of the arts, but also because of its many distinguished writers and its not inconsiderable critical and creative work in all departments of literature. Yet this is precisely what is frequently done. Not that Catholic writers are neglected. That would be perhaps the better part. But they are bunched indiscriminately with those authors and movements which belong either by choice or by convention to the “old world.”

Thus it is customary today to speak of prominent Catholic authors as belonging to what is called the Classical Revival, just as forty years ago it was customary to speak of them as belonging to the neo-Romantic revival. Because the philosophical and historical criticism of men like Christopher Dawson, Douglas Woodruff, E. I. Watkin, Jacques Maritain, and Henri Massis, is one that calls for a return to order, they are classed in globo with all proponents of “law and order”; they are conservatives. Catholic poets and critics are labeled “anti-Romantic” or “Romantic”; they are conceived as belonging to the “Revolutionary Right” as opposed to the “Revolutionary Left,” and so on.

But, in all truth, none of these designations fits Catholic literature. One even wonders whether they fit anything anymore. They are all the worn-out counters of that old world which for generations has kept itself alive by a series of reactions, of rebellions, and inevitable returns to “order,” of rationalism and antirationalism, of romanticism and conservatism, and of numerous other oscillations in all human fields. That pendulum of reaction today swings in an increasingly small arc; it has almost reached dead center. The difference between Capitalism and Bolshevism, between the “classicism” of Ezra Pound and that of the loosest Romantic, is almost entirely a matter of words. All those vital differences that once gave a semblance of life have disappeared, leaving only monotonous uniformity from which little notable vitality results.

Catholic literature is written by those who intellectually have stepped clear of this “waste land” into a world full of an abundant and varied life. Physically they still remain in the old order that lingers on about them, and it is, I suppose, inevitable that the numerous schools, tendencies, individual artistic preferences existing among modern Catholic authors should be called “romantic” or “classical” or “traditional” or “modernist.” But these terms must be applied with a difference. And that difference is fundamental and of great importance.

This essay is the second part of the Introduction to The Catholic Literary Revival. Read the first part here.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

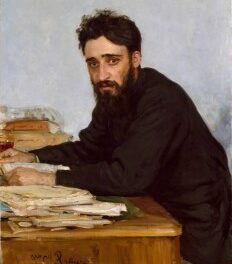

The featured image is “Viktor Rydberg” (1890) by Anders Zorn, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News