We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Key Points and Summary: On December 26, 2024, the U.S. Army’s Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system achieved its first combat intercept during a Houthi ballistic missile attack on Israel.

-This marks a milestone for the $23 billion defense system, designed to counter short- and medium-range ballistic missiles. THAAD’s “hit-to-kill” technology and advanced AN/TPY-2 radar showcased their effectiveness, bolstering missile defense capabilities in the Middle East.

-As global tensions rise, with nations like Iran, China, and Russia improving their ballistic missile arsenals, THAAD’s successful operation highlights its critical role in U.S. and allied defense strategies.

THAAD Makes History: U.S. Army Intercepts Houthi Missile Bound for Israel

Two weeks ago, on December 26, 2024, missile defense radars overwatching the Middle East and the Red Sea detected an object hurling at many times the speed of sound on a northward-bound trajectory towards Israel—a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) launched by Houthi rebels in Yemen to traverse the over 700 miles separating Yemen from Israel.

The Houthis had already launched dozens of MRBMs as well as long-range kamikaze drone attacks at Israel since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war over a year ago on October 6, 2023—and so far, all but a few of these attacks had been successfully detected and intercepted by a combination of Israel’s multi-layered air defense systems and United States warships, warplanes, and American ground-based Patriot missiles based in the Middle East.

However, Something different happened: a recording from inside Israel shows a glowing ball of light surging up from the ground and vanishing into the clouds above. An observer in the video comments that he had been “waiting 18 years for this.”

That comment made sense when US officials reported that a US Army had just successfully executed its first combat intercept of an enemy missile using its Terminal High-altitude Area Air Defense System (THAAD), which entered service in 2009 (15 years ago).

The THAAD’s combat debut outside US services came nearly three years ago, on January 17, 2022, when a battery exported to the United Arab Emirates downed a Houthi MRBM bound for an oil facility near Al Dhafra Airbase.

The first of two Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) interceptors is launched during a successful intercept test. The test, conducted by Missile Defense Agency (MDA), Ballistic Missile Defense System (BMDS) Operational Test Agency, Joint Functional Component Command for Integrated Missile Defense, and U.S. Pacific Command, in conjunction with U.S. Army soldiers from the Alpha Battery, 2nd Air Defense Artillery Regiment, U.S. Navy sailors aboard the guided missile destroyer USS Decatur (DDG-73), and U.S. Air Force airmen from the 613th Air and Operations Center resulted in the intercept of one medium-range ballistic missile target by THAAD, and one medium-range ballistic missile target by Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD). The test, designated Flight Test Operational-01 (FTO-01), stressed the ability of the Aegis BMD and THAAD weapon systems to function in a layered defense architecture and defeat a raid of two near-simultaneous ballistic missile targets.

Still, a conventional missile intercept or two is a poor return for the estimated $23 billion and growing the US invested in THAAD.

But intensifying regional conflicts, the proliferation of medium/intermediate-range ballistic missiles, and worsening international tensions make the investment in THAAD appear more relevant than ever in the mid-2020s.

How THAAD works

THAAD batteries, officially operated by 95 US Army personnel each but trained and sustained by the US Missile Defense Agency, are charged with defending key military bases and nearby population centers from attacks by short- medium- and even intermediate-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs, MRBMs, and IRBMs) used to deliver conventional or nuclear attacks.

In the last decade, such missile weapons have been used extensively in combat with conventional warheads by Iran, Houthi rebels, and Russia. In the longer term, North Korea and China have also built substantial ballistic missile arsenals effective against targets across East Asia.

The US Army has received deliveries of over 800 THAAD missiles and musters seven THAAD batteries, with an eighth battery set in production in Alabama. Two of these units are indefinitely forward deployed in Guam and South Korea. A third THAAD was deployed to Israel in October 2024 in anticipation of an Iranian missile attack, joining a compatible AN/TPY-2 radar unit and a Patriot battery already deployed there.

THAAD isn’t, however, designed to intercept the even faster and higher-flying class of intercontinental-range missiles (ICBMs) dedicated exclusively to nuclear attacks, so it makes little sense for homeland defense of US cities that only ICBMs could plausibly reach.

Each US Army THAAD battery consists of six truck-based launchers, though up to eight are supported and positioned in a dispersed fashion to expand geographic coverage angles and reduce vulnerability to enemy strikes. Kill one launcher, and those scattered elsewhere can still do the job.

A THAAD battery uses a powerful AN/TPY-2 long-range X-band radar to acquire targets. The system can detect some high-altitude targets as far as 1,900 miles away. To engage detected threats, one or two Tactical Operation Centers draw on the tracking data from the AN/TPY-2 to calculate firing solutions and issue launch commands to launchers.

Each launcher carries eight interceptor missiles that can accelerate up to Mach 8, or over 1.5 miles per second. These one-ton missiles, costing over $12 million each, have a rocket booster but no explosive warheads. Instead, after jettisoning their rocket booster, they rely on an infrared imaging seeker to precisely home in on and impact the targeted missile incoming at many times the speed of sound. These ‘hit-to-kill’ interceptors can officially intercept incoming ballistic threats up to 125 miles away at up to 600,000 feet high.

A battery’s components are designed for easy air transportability and support drawing power from the local power grid in addition to the field alternative of using gas-powered generators.

מערכת ה- THAAD האמריקנית לקחה חלק ביירוט הטיל הבליסטי ששוגר אמש מתימן. אפשר לשמוע את אחד החיילים האמריקניים מתרגש “18 שנים חיכיתי לזה” pic.twitter.com/s4VoMfMhaF

— איתי בלומנטל 🇮🇱 Itay Blumental (@ItayBlumental) December 27, 2024

In the bigger picture, THAAD batteries are a ‘medium’-layer defense falling between shorter-range Patriot PAC-3s batteries—effective against SRBMs—and the national-level GMD system for protecting the US against a small-scale ICBM attack. Navy warships also deploy SM-6 and SM-3 anti-ballistic missile interceptors comparable to or exceeding THAAD interception capabilities.

Meanwhile, the UAE operates two THAAD batteries, while Saudi Arabia may receive up to seven. US allies also deploy THAAD-like systems, notably Israel’s Arrow missile family—now being procured by Germany. South Korea has the L-SAM, which entered service in 2024.

France fields the Aster 30 Block 2 missile due in 2026 for SAMP/T air defense batteries.

Why Ballistic Missile Defense Is Growing More Important

China and Russia have historically protested the US deployment of THAAD in Asia and Europe, claiming the battery is intended to weaken strategic nuclear deterrence. But setting aside the scary possibilities of nuclear warfare, it’s apparent non-nuclear ballistic missiles play a significant role in the military power of China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia to offset the US’s advantages in airpower and, to an extent, even sea power.

Notably, in the fall of 2024, Russia prominently combat tested a new Oreshnik conventionally-armed intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which Putin billed as intended to deliver precise attacks on targets across Europe, even though IRBMs heretofore were seen as nuclear-only weapons.

Blunting such threats is essential, and in a NATO-Russia conflict, one might expect US THAAD batteries to be rush deployed to protect bases in the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, and Poland. Conversely, a war in East Asia might see THAAD units deploy to Guam, Okinawa, and other Japanese islands. Hawaii, Singapore, and Australia could benefit from THAAD deployment in some contexts.

Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran have all fielded or tested new hypersonic glide-vehicle weapons, which can maneuver more extensively in the atmosphere, making their trajectory much less predictable and more challenging to track and intercept.

These might undermine the protection offered by THAAD. However, the US is also moving forward with countermeasures, including the recent deployment of satellite-based downwards-looking sensors to help track hypersonic gliders, as well as an upgrade of the AN/TPY-2 radar used by THAAD to a higher-resolution gallium-nitride phased array and work integrating THAAD into the Army’s IBCS air defense network.

Organizationally, responsibility for THAAD sustainment is due for transfer from the MDA to the Army, but the service wants compensatory funding for such a transition.

In any case, virtually all of the US’s most likely future military adversaries have large and improving ballistic missile forces—both traditional and hypersonic—and would use them liberally even in a strictly non-nuclear conflict.

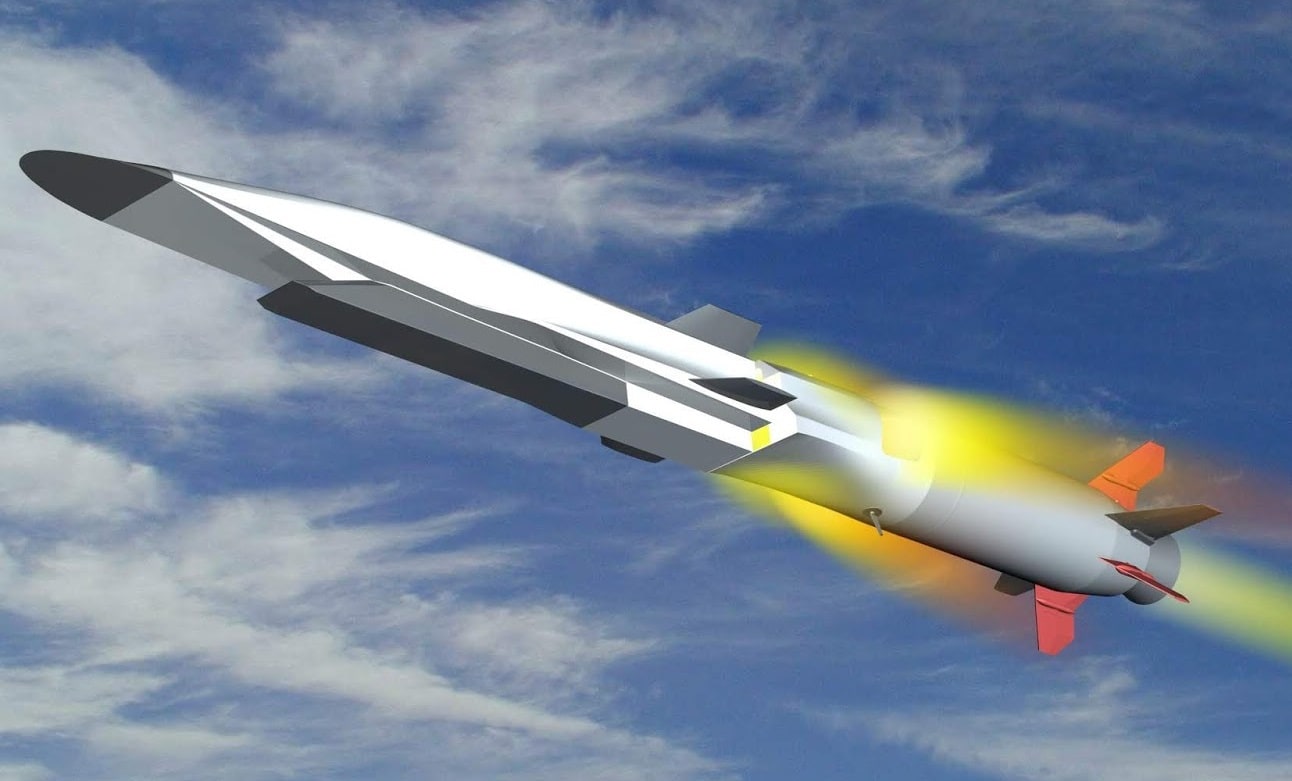

Tsirkon Hypersonic Missile. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

In that context, THAAD could prove critical to keeping US personnel and civilians alive should the skies rain fire in future conflict. Thus, the THAAD intercept last December could prove the first milestone in what risks proving a busy operational career.

About the Author: Sebastien A. Roblin

Sébastien Roblin writes on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including The National Interest, NBC News, Forbes.com, War is Boring and 19FortyFive, where he is Defense-in-Depth editor. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News