We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

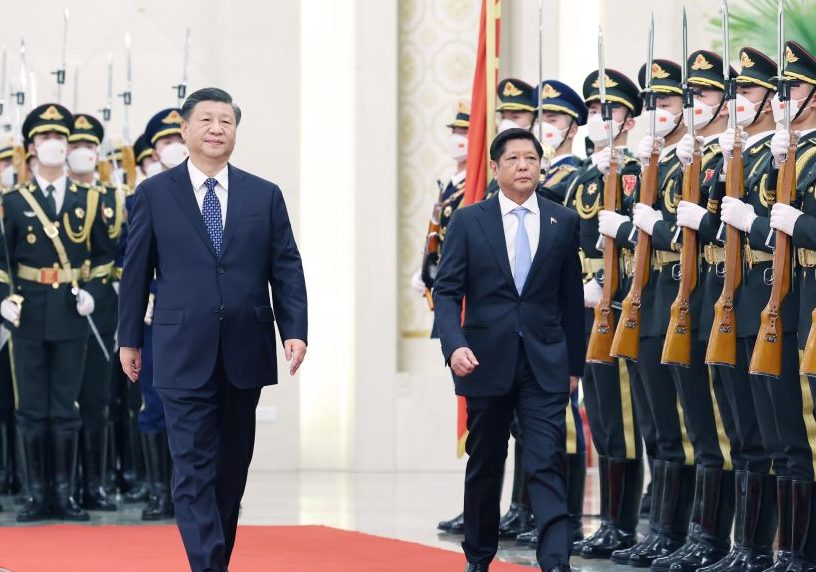

In April 2024, a spokesperson for former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte suggested that the Philippines and China had entered into an undisclosed ‘gentleman’s agreement’ between 2016 and 2022. China would not challenge the status quo in the West Philippine Sea, and the Philippines would send only basic supplies to its personnel and facilities on the Ayungin Shoal. But now, the Philippines is emerging as an essential player in resisting China’s strategic ambitions in the region, with President Ferdinand Marcos’s administration asserting Philippine maritime claims through naval confrontations and new legislation.

This comes at a time when the country is facing a quieter, but equally serious, threat at home. The recent, high-profile case of Alice Guo—a former mayor accused of graft, money laundering, and espionage—shows how domestic corruption leaves the Philippines vulnerable to Chinese infiltration and subterfuge. How the Philippines navigates this challenge could shape not only its future but also the broader stability of Southeast Asia.

In addition to conducting aggressive military manoeuvres in the surrounding seas, China is also pursuing strategic investments and subtler forms of manipulation to push Philippine leaders (at all levels of government) into a more China-friendly stance. This is in keeping with its global strategy of building influence through clandestine business alliances, economic incentives, and investments targeting other countries’ elites. As the Philippines approaches critical elections in 2025 and 2028, China will try to befriend or otherwise gain sway over anyone who is open to its overtures.

Given these efforts, one cannot rule out a future Philippine government that adopts China’s own model of governance, state control and mass surveillance. Such a government might not only consult China’s authoritarian playbook to quash dissent; it could also leverage China’s resources and international political support to evade scrutiny and accountability. Institutions meant to serve the Philippine people would become tools for monitoring and restricting opponents and critics, and China will have secured itself a valuable foothold in Southeast Asia.

China has been stepping up its information operations globally, using the Philippines as a testing ground for tactics designed to propagate anti-American narratives and build pro-Chinese sentiment. Through platforms such as Facebook and TikTok, which many Filipinos rely on for news, Chinese accounts amplify content that casts doubt on Philippine-US relations and erodes social trust within Philippine society.

By exploiting internal instability, Chinese influence operations aim to distract Philippine authorities from China’s own aggression in the surrounding seas. One potential source of disruption is the lead-up to the elections in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). Should an ongoing peace process there falter, the region would inevitably demand much more of the national government’s attention and resources.

What can be done? Even if US investments do not match the scale of China’s infrastructure projects in the Philippines, Western strategic aid can help by presenting a clear alternative to China’s debt-driven model. Such a strategy would not only support Philippine sovereignty but also strengthen America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

Specifically, to counter Chinese interference, the US and its allies should direct investments and support to advance five priorities. First, since corruption is a national security threat, they should fund programs to ensure disclosures of beneficial ownership (who ultimately owns private businesses), debt transparency, and the integrity of public procurement and tendering processes. This would not only create a level playing field for all businesses; it would also help safeguard Philippine institutions and political processes from covert foreign manipulation.

Second, the integrity of elections must be strengthened. Long-term election monitoring can help expose and counter covert foreign influence efforts and misuses of resources, ensuring transparency beyond election day. If sufficiently supported, citizen-led observation efforts can reinforce the sense that the process is fair, making electoral institutions more resilient against external pressures.

Third, the Philippines’ allies need to protect the BARMM peace process, such as by funding initiatives that strengthen local governance and security institutions in the region.

The peace process, and the country more broadly, would also benefit from enhanced information security, including targeted support for local initiatives to improve the public’s digital news literacy.

Lastly, the Philippines needs help countering Chinese surveillance of its citizens and officials. US support for cybersecurity and programs to protect digital rights can frustrate Chinese influence tactics and provide more transparency on major digital platforms.

A stable, democratic Philippines is vital to US interests and regional security. America and its Indo-Pacific partners and allies must do more to help the country build resilience against Chinese aggression not only in its territorial waters, but also in its politics.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News