We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Key Points and Summary: China’s growing amphibious fleet, exemplified by its Type 071, Type 075, and the newly launched Type 076 assault ships, signals ambitions far beyond Taiwan.

-These vessels enable China to protect vital sea lanes, rescue citizens abroad, and safeguard its global investments in unstable regions, such as Africa.

U.S. Marines with Bravo Company, 2d Assault Amphibious Battalion, 2d Marine Division approach the USS Wasp (LHD 1) in assault amphibious vehicles off of Onslow Beach during a three-day ship-to-shore exercise on Camp Lejeune, N.C., June 27, 2020. During the exercise, the Marines conducted amphibious maneuvers and dynamic ship-to-shore operations with the USS Wasp (LHD 1). (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jacqueline Parsons)

-The Type 076, with advanced EMALS launch systems and enhanced aviation capabilities, highlights China’s intent to project power globally.

-However, to fully capitalize on its expanding fleet, China must establish more overseas bases. The shift reflects China’s strategic response to vulnerabilities, including its embarrassing 2011 Libya evacuation, emphasizing its need for regional military readiness.

Establishment of China’s Amphibious Fleet Goes WAY Beyond a Taiwan Scenario

China stepped up the building of its amphibious assault fleet in 2006 by commencing construction of the Type 071 class. The nation has reached its apex with the Type 076 class, vessels that can transport hundreds of marines, equipment, and vehicles.

China’s Navy is necessary due to its reliance on raw materials that must travel waterways, which could quickly become disputed. China’s amphibious fleet allows it to protect and extract its citizens from dangerous situations, such as state collapse and instability. China must construct a network of foreign military bases to capitalize on its power projection capabilities. Currently, China has a single military base in Djibouti.

The Incredible Capabilities of Amphibious Assault Ships

Amphibious assault ships give the nation operating them numerous options. First and foremost, these vessels are platforms for power projection. A U.S. Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) comprises approximately 2,200 Marines and all their associated vehicles and equipment.

According to the U.S. Marine Corps, an MEU is ready to respond within six hours of notification and has 15 days of organic, sea-based logistics.

During an operation, the Marines of a MEU would also be able to count on organic air support launched from the assault ships that carried them. If called upon, these Marines can rapidly launch devastating assaults or raids, blowing a hole in an enemy’s defenses and preparing a way for follow-on forces.

Additionally, the vessels of an MEU can readily deploy for humanitarian aid/Disaster relief and evacuations of US citizens in a crisis. The forward-deployed nature of an MEU deters aggression and assures and strengthens alliances through training missions.

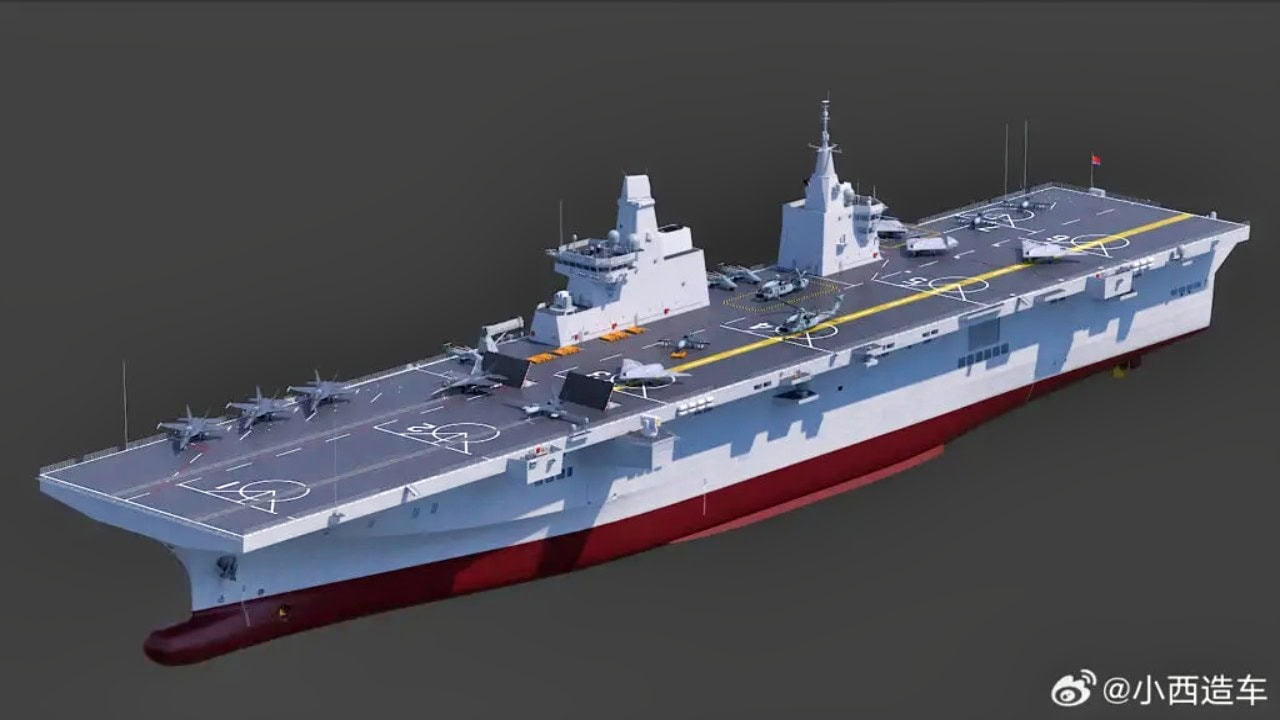

Type 076 China Amphibious Assault Ship.

The Genesis of China’s Amphibious Fleet

China’s modern amphibious fleet began to take shape in 2006 with the launch of the first Type 071 Landing Platform Dock.

This vessel has a displacement of 25,000 tons when fully loaded. It has a floodable well deck to launch military hovercraft (LCAC) and amphibious tanks. An aft helicopter landing pad and hangar to accommodate four helicopters. The Type 071 can also transport and deploy a landing force of up to 800 marines. The Chinese Navy (PLAN) has eight vessels in its inventory currently.

The Next Step in China’s Amphibious Evolution: Type 075

Following the induction of the type 071 class, the amphibious ship-building binge did not stop; it only increased in size and scope. By 2021, the PLAN commissioned its first Type 075 Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) on April 23, 2021.

Since then, China has constructed and launched three additional vessels of this class. The crew of this vessel consists of approximately 1,100 sailors, and its ground component comprises 1,000 to 1,600 marines.

The Type 075 is comparable in size to the U.S. Navy Tarawa and Wasp-class LHD, displacing approximately 35,000 tons. Regarding combat air operations, the Type 075 can accommodate 30 helicopters for rapidly transporting its Marines ashore and providing them with resupply and air support.

In its cavernous interior space, the Type 075 has the capacity to transport and launch three LCACs, and according to the U.S. Naval War College, unofficial estimates state that the Type 075 can transport 10 main battle tanks, 20 to 35 Type 05 light amphibious tanks, 20 infantry fighting vehicles, and 50 general purpose field trucks.

Type 055 Destroyer from China. Chinese Navy Handout/State Media.

Speculation Became Reality

Even while the Type 075 was still an engineering layout in a CAD program, there was speculation of an even larger more capable amphibious vessel. True to form, the Type 075 was not the be-all-end-all; it was just a stepping stone to the Type 076, the largest amphibious assault ship in the world, officially launched on December 27, 2024.

Chinese media stated that the Type 076 displaces 40,000 tons, yet it is speculated that the displacement is closer to or slightly exceeds 50,000 tons.

The EMALS launching system is a significant difference between this vessel and previous PLAN amphibs. Only found in the newest carriers, this system will provide the Type 076 and its accompanying task group with air control via its complement of fixed-wing fighter aircraft.

It is unlikely that LCACs will launch from the Type 076, given that additional space appears to be allocated to an enlarged hangar, aviation fuel storage, and aircraft ammunition storage. Additionally, the ground component may be of similar size to the Type 075 due to this reduction in space.

Coinciding with its increased combat air capabilities is another unique feature: its dual superstructures. Each superstructure has different responsibilities, and keeping them separate reduces confusion during complex operations.

The forward superstructure focuses primarily on navigation and coordinating the movement of the vessels within the task group. The aft superstructure has the primary responsibility of launching the ships manned aircraft, drones and the overall operation of the flight deck.

Additional responsibilities include coordinating and supervising the overall operations of the aircraft in the task group, as the Type 076 serves as a command ship.

The Big Question: Why is China Constructing a Powerful Amphibious Fleet?

PHILIPPINE SEA (Oct. 3, 2021) The U.S. Navy Nimitz-class aircraft carriers USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70) and USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) transit the Philippine Sea during a photo exercise with multiple carrier strike groups, Oct. 3, 2021. The integrated at-sea operations brought together more than 15,000 Sailors across six nations, and demonstrates the U.S. Navy’s ability to work closely with its unmatched network of alliances and partnerships in support of a free and open Indo-Pacific. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Michael B. Jarmiolowski) 211003-N-LI114-1208.

The first thought would be to further its ability to launch an invasion of Taiwan successfully. This would not be wrong; China’s growing amphibious fleet has a massive role in any cross-strait operation.

China’s amphibious fleet is still developing. Therefore, it will not carry its entire invasion force. The PLAN amphibs will likely transport the initial shock troops, the most highly trained expeditionary forces, to be followed on by additional army units carried by civilian transport vessels.

However, beyond Taiwan, China needs an insurance policy to safeguard the vast amounts of natural resources it imports and depends on and protect its citizens working and living in foreign countries.

The Big Picture: Natural Resources and Chinese Nationals Working Abroad

In 2001, China became the 143rd World Trade Organization member country. At that time, China was described as a “world factory.” In order to manufacture any finished product, a factory requires raw materials.

In China’s case, it sources those raw materials from various and distant global locales. The supply lines or sea lanes of communication (SLOC) that bring those resources to China are very vulnerable to potential disruption.

The U.S. Navy patrols virtually every major shipping lane and could theoretically cut off China’s merchant fleet. To further complicate matters, India, who is no friend of China due to China’s semi-recent hostile behavior along their shared border, could also disrupt China’s merchant shipping routes. This is particularly true of the Strait of Malacca, a waterway that passes two-thirds of China’s trade and eighty percent of China’s oil imports.

China, therefore, requires a robust navy to protect its SLOCs, transit routes for trade and raw materials, and an effective amphibious fleet to protect the sources of mineral extraction and its citizens working abroad , particularly in less stable countries or regions.

China’s Raw Materials Imports by the Numbers

A country with such a large population has some impressive statistics to report. Forty percent of Africa’s mineral exports and one-third of its ore and metal exports ship to China. In 2022, China-Africa trade volume reached nearly 300 billion, triple the trade volume between the US and African countries. China receives up to three-quarters of global seaborne iron ore. Some of the primary sources of this trade are Australia, Brazil, and India. Approximately half of China’s oil imports come from the Middle East. Saudi Arabia is the primary supplier, with Iraq, Oman, Kuwait, and the UAW among China’s other suppliers. Latin America is a significant food supplier to China, supplying it with approximately one-third of its food imports. Primary exports include soybeans, coffee, sugarcane, cherries, shrimp, beef, and fishmeal.

Missile Launcher in Taiwan. Image: Creative Commons.

China Desperately Needed the Capabilities to Protect its Citizens Working Abroad

American citizens under duress can count on the U.S. Department of State work with foreign governments if they find themselves in legal trouble abroad.

In a scenario where a local government does not have the means to protect or rescue an American citizen, well…Delta Force or Seal Team Six will deploy, blow the door off its hinges, empty mags and rescue said American citizen or citizens. Such was the case of Philp Walton and his rescue by Seal Team Six operators in Nigeria, in 2020.

Until recently, China did not have this capability, and in reality, it’s still in development, but it’s getting a lot closer.

According to the China’s State Council, by September 2024, 1.01 million Chinese nationals were working in a foreign country. According to the Voice of America 88,371 were working in Africa, a continent that has suffered eight coups within the last three years.

The need to be able to rescue its citizens abroad came to a head in 2011, when the Libyan dictatorship of Muammar Gaddafi collapsed. At that time, China had 13,500 citizens working in Libya when the civil war erupted.

China’s response resulted in a national embarrassment for the world to observe. In order to safely evacuate its stranded citizens, the Chinese government, lacking any regional resources (military or otherwise), was forced to rent three cruise ships and 100 buses from Greece, in order to rescue its citizens.

China’s Strategic Response

The Libya fiasco marked a turning point for China, from that point forward, it was decided to pre-position its military and logistic supply chains in order to more swiftly respond to any similar future emergencies.

It should then be of little surprise that in 2017, China opened its first overseas military base in the East African country of Djibouti, which sits at the southern entry point of the Red Sea.

This facility features an extended pier that can dock the PLAN’s aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships. This gives China the ability to launch expeditionary operations deep into Africa in order to assist Chinese citizens, protect its investments and pressure or reinforce African governments if needed.

New Taiwan F-16V fighter jet. Image Credit: ROC government.

The Current State of China’s Amphibious Affairs

China has the amphibious capabilities to launch a robust military operation far from its shores. To fully cement this capability, China needs to construct many more naval bases in strategically important areas.

While China has only one official military base, it can also rely on its commercial shipping ports for military purposes. Remembering that China maintains civil-military fusion about its commercial ventures is essential. To this point in 2021, COSCO, a major Chinese shipping company, managed 367 berths at 37 ports worldwide. This gives China numerous spaces to dock its PLAN vessels.

While the Chinese amphibious fleet is still growing, it is nonetheless competent. It will continue to grow due to China’s massive overseas investments and its great reliance on imported raw materials.

About the Author: Christian P. Martin

Christian P. Martin is a Michigan-based writer; he earned a Master’s degree in Defense & Strategic Studies (Summa cum laude) from the University of Texas, El Paso. Currently, he is a research assistant at the Asia Pacific Security Innovation Forum. Concerning writing, he has published several dozen articles in places like Simple Flying, SOFREP, SOF News, and other outlets.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News