We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Key Points and Summary: Russia’s navy faces severe challenges as attrition, outdated equipment, and shipyard issues undermine its capability. Losses in the Black Sea, notably the Moskva, have decimated the fleet, while aging vessels like the Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier and Kirov-class battlecruisers struggle for relevance.

-Limited shipbuilding capacity and geopolitical constraints exacerbate the decline, trapping fleets in the Black and Baltic Seas due to NATO’s expanded presence. Submarine programs like the Borei and Yasen classes provide some strength, but overall naval power is dwindling.

-Without substantial reform or external aid, such as Chinese-built ships, the Russian navy risks long-term irrelevance.

Why Russia’s Navy Is Struggling to Stay Afloat Amid Mounting Challenges

Back in the summer of last year, a key aide to Russian President Vladimir Putin declared that Russia remains “a great maritime power,” and that new programs of construction would restore Russia’s presence on the high seas.

Unfortunately for Russia, there seems to be little prospect in the near or medium-term future for a restoration of Russian naval might. The losses inflicted by Ukrainian forces in the Black Sea, combined with a moribund shipbuilding industry and a dire geopolitical situation, mean that Russian maritime power is at one of its lowest ebbs since the dawn of the 20th century.

Attrition Issue for the Russian Navy in Black Sea

Attrition of the Black Sea Fleet has been severe, probably to the degree that Putin regrets deploying elements of the Baltic Fleet to support the invasion of Ukraine.

Twenty-six vessels have been lost or damaged beyond economical repair as of the summer, and the rest of the fleet has fled to the distant eastern reaches of the Sea in order to avoid Ukrainian attacks.

The problem with the Black Sea Fleet isn’t just that the confines of the Black Sea have left it unable to maneuver; it’s also that the ships themselves are old and have not been updated with modern defensive systems.

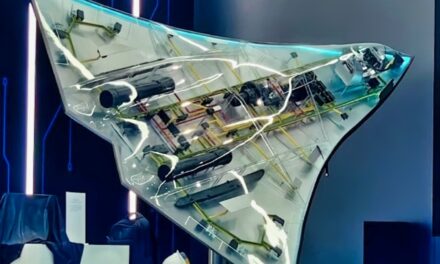

Yasen submarine diagram from Russian state media.

RFS Moskva was lost in part because her key systems had not been updated and were in some cases non-functional. Lack of access to the Ukrainian shipyards at Mikolayiv (a major and unfulfilled Russian war objective) has made it impossible to build new ships or to update and repair older vessels.

Russia’s Legacy Naval Fleet

The attrition of the Black Sea Fleet is obviously important, but too much focus on losses tends to obscure Russia’s poor naval position at the beginning of the war.

The legacy fleet has several important assets, although at this point, it is leaning very heavily into legacy rather than actual capability. Like RFS Moskva, most of the Russian Navy’s major units are old and have critical technological vulnerabilities that Russia probably cannot economically remedy.

Battlecruisers

The two remaining Kirov-class battlecruisers remain potent political symbols and platforms for offensive warfare. However, both ships are forty years old and face uncertain futures. RFS Pyotr Velikiy has long carried the mantle of Russian naval power, conducting global cruises and demonstrating presence around the world. Her sister, Admiral Nakhimov, has been undergoing modernization for the past six years, and will reportedly re-enter service in 2026.

Russia’s Borei-class ballistic missile submarine.

The Russian Navy had intended to modernize Pyotr Velikiy after Nakhimov returned to service, but those plans have evidently been put on hold. Assuming that Nakhimov returns to service she will carry a formidable armament, but as the only major Russian naval unit in existence the strategic impact of her return is unclear.

The Old Aircraft Carrier: Admiral Kuznetsov

Russia’s aircraft carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov, is unlikely ever to launch aircraft in combat conditions again. After a brief deployment off Syria the Kuznetsov entered a long, accident-filled period of overhaul and repair.

The current physical state of the ship, which originally entered service in 1991, is reportedly dire. More importantly, the six years out of service has allowed the human capital of Russian naval aviation to wither on the vine.

Without a trained cadre of pilots and aircrew, operations off of an aircraft carrier are effectively suicidal. Thus, even if Kuznetsov returned to service it would take considerable time and trouble to reconstitute her airgroup. The only shortcut available to Russia would be for pilots and aircrew to retain their proficiency by training on Chinese or Indian aircraft carriers, but at the moment there is no indication that this is taking place.

The Other Warships

The rest of the Russian surface fleet consists of two Slava class cruisers (sisters of RFS Moskva) built in the 1980s, ten destroyers built in the 1980s and 1990s, a dozen frigates of more modern vintage, and a large number of smaller warships and support vessels.

Russian Navy. Image: Creative Commons.

These ships are divided between Russia’s five major fleet commands (Black Sea, Pacific, Baltic, Northern, and Caspian) and cannot easily be concentrated in times of crisis. Worse, Russia’s moribund shipbuilding industry (a problem tied directly to the Russia-Ukraine War) has made it awfully difficult to envision replacement of the most aged components of the Russian Navy.

Submarines

Russia is still capable of building submarines, and fortunately Russia’s most important strategic maritime interest operates below the sea. The seven boats of the Borei class nuclear ballistic missile submarine program have provided Russia with another thirty years of strategic nuclear deterrent, while the five Yasen class cruise/attack nuclear submarines offer tactical flexibility.

These ships are supplemented by some three dozen legacy submarines of both nuclear and conventional build, although the deployability of these older ships remains in considerable question.

Geography

Russia’s biggest maritime problem now and throughout history has been geography. Despite its immense size, Russia lacks good, accessible ports that can be used year-round to project power. Indeed, Russia’s fleets have historically been incapable of supporting one another during wartime.

The Ukraine War has exacerbated these difficulties to a near-fatal degree. As long as hostilities continue (and this could be for a good long while), naval forces can neither deploy into or out of the Black Sea; it has effectively become a prison for the Russian Navy. The Russian Baltic Fleet undoubtedly has the same sense of being under detention, especially since the accession of Finland and Sweden into NATO. Helsinki’s accession has also undoubtedly caused deployability headaches for the Northern Fleet, which operates from bases in easy range of Finnish reconnaissance.

Kirov-Class. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The situation of the Pacific Fleet is somewhat better, but it is badly outclassed by the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) and the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). In any open hostilities against the NATO alliance, the Russian Navy would find itself in a dire situation.

What Happens Next for Russia’s Navy?

At the moment, Russia has more significant problems than the state of its Navy, and funding for the Navy appears to have been correspondingly reduced in preference for more critical needs. In the long run the existing fleet is getting older and less capable, while the Russian shipbuilding industry shows few signs of life.

If Russia finds itself at peace and able to afford new ships, its best bet is probably to buy them from China. Whether Moscow could acknowledge this reversal of the traditional military relationship between the two countries is a different question.

Modern Russian Navy Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

About the Author: Dr. Robert Farley

Dr. Robert Farley has taught security and diplomacy courses at the Patterson School since 2005. He received his BS from the University of Oregon in 1997, and his Ph. D. from the University of Washington in 2004. Dr. Farley is the author of Grounded: The Case for Abolishing the United States Air Force (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), the Battleship Book (Wildside, 2016), Patents for Power: Intellectual Property Law and the Diffusion of Military Technology (University of Chicago, 2020), and most recently Waging War with Gold: National Security and the Finance Domain Across the Ages (Lynne Rienner, 2023). He has contributed extensively to a number of journals and magazines, including the National Interest, the Diplomat: APAC, World Politics Review, and the American Prospect. Dr. Farley is also a founder and senior editor of Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News