We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Can you imagine the danger to our republic if the Executive Branch could secretly, for months on end, and without any clear and compelling justification, surveil the very people in Congress conducting oversight of those agencies?

That chilling constitutional nightmare transpired. And we’re only getting the details about the separation-of-powers-eviscerating, civil liberties-undermining, and transparency-imperiling activity seven years after it started.

The revelations come in a recently released Justice Department Inspector General report. Like much of this corrupt activity, the story begins with Russiagate. In the spring and summer of 2017, the first year of the Trump presidency, CNN, The New York Times, and The Washington Post published articles containing classified information concerning Trump and Russia.

Among the unauthorized disclosures to emerge was that a FISA warrant had been issued to surveil Trump’s foreign policy adviser Carter Page. The dubious warrants would be renewed four times.

Page was framed as a Russian agent through authorities’ omission of critical exculpatory information and reliance on the dodgy Steele dossier that federal investigators could never corroborate. An official would later be prosecuted for doctoring information about Page used to justify FISA warrant renewal.

Page’s reputation was destroyed, and his rights violated, all as part of a fishing expedition into Trump world that had the added benefit from the perspective of the Deep State of fueling the narrative that the president too was a Russian agent. Indeed, the revelations added smoke to the phony Trump-Russia collusion fire that would consume the first two years of his administration.

Federal authorities went on a mole hunt for the Russiagate leaker. Between 2017 and 2018, prosecutors issued subpoenas for non-content records for phone numbers and email addresses covering two members of Congress and 43 staffers — Democrats and Republicans alike — on grounds they may have accessed the classified information before it wound up in the papers.

The justification in most cases was simply “the close proximity in time between that access and the subsequent publication of the news articles,” the IG found.

The records included information like text message logs, email recipient addresses, and call detail records indicating who initiated communications, with which numbers, dates, times, durations, etc. The records would have provided a map to the professional and personal lives of those surveilled.

In myriad instances the feds sought non-disclosure orders from courts too. The NDOs prevented communications companies from apprising the congressmen and staffers that their records had been subpoenaed. In other words, they ensured the surveilled overseers of those doing the surveilling were kept in the dark.

The DOJ obtained 40 NDOs, approximately 30 of which were renewed at least once, and most of which were repeatedly renewed — some extending up to four years.

One of those targeted was a then-top staffer for Senate Judiciary Ranking Committee member Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, Jason Foster. I previously detailed his efforts to get to the bottom of the subpoena effort in a RealClearPolitics profile of his Empower Oversight nonprofit. The Senate Judiciary Committee was probing the Trump-Russia investigation.

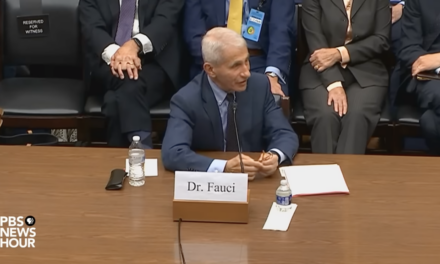

So too was the House Intelligence Committee chaired by then-California Republican Congressman Devin Nunes. One of his top investigators, Kash Patel, who is now Trump’s pick to lead the FBI in his next term, also had his records subpoenaed. Patel would help expose the feds’ abuses with respect to the Carter Page FISA warrants in helping author the so-called “Nunes Memo,” and much of the other corruption of the Russiagate investigators. Former Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein reportedly threatened to subpoena Patel’s communications, as well as those of his colleagues, in January 2018, weeks prior to the release of the memo, over their vigorous investigating of the investigators.

Little did Patel know that those communications records were already being collected under subpoena, under requests covering data dating back to as early as Dec. 1, 2016. Foster and Patel didn’t know their records had been subpoenaed until the Biden years when the communications companies were permitted to disclose the secret subpoenas.

To make things more perverse, the DOJ’s NDO applications to the courts did not specify that those to be kept in the dark about their subpoenaed records were members of Congress or staffers. The NDOs also “relied on general assertions about the need for non-disclosure rather than on case-specific justifications. Department policy at the time did not require including information in applications about whose records are at issue,” according to the IG. DOJ policy permitted and still permits “prosecutors to make boilerplate statements in NDO applications.”

When news reports emerged during the Biden years of what had transpired, DOJ issued a new congressional investigations policy ostensibly requiring greater scrutiny of and higher-level approvals for subpoenas and NDOs, while still not requiring approval from or notification of the attorney general or deputy attorney general — not that any such processes necessarily would have prevented such malfeasance. Only after reviewing the IG report in September of this year did DOJ even create rules mandating that prosecutors disclose to the court when an NDO involves a congressional office or staffer.

Another notable takeaway from the IG report is that the bar to subpoena communications records from members of the media is actually higher than that from members of the legislative branch. Unlike the DOJ’s News Media Policy, the Congressional Investigations Policy contains no “exhaustion requirement.” Prosecutors need not exhaust “all other reasonable means of identifying the sources of the unauthorized disclosures,” prior to seeking a subpoena. Only then, in the case of news media, must the feds request “Attorney General authorization.”

Remarkably, even after modifying its Congressional Investigations Policy, according to the IG, it is not clear that illegal leaks are subject to the policy. The policy is located in a chapter of DOJ’s Justice Manual called “Protection of Government Integrity,” the first provision of which states that the chapter deals with crimes “including bribery of public officials and accepting a gratuity, election crimes, and other related offenses.” Unauthorized disclosures do not make the list.

So why couldn’t this exact episode play out again?

The IG concluded that though it could not find evidence of “retaliatory or political motivation” for the issuance of the subpoenas, efforts like these risk “chilling Congress’s ability to conduct oversight of the executive branch,” and at minimum create “the appearance of inappropriate interference” by that branch “in legitimate oversight activity.”

One need not think hard about how a dishonest or corrupt national security apparatus could use the predicate of an illegal leak to spy on political foes for nefarious ends. The mere possibility that could happen, as the IG suggests, is corrosive to our system. And it’s worth noting that in the case at hand, no leaker was ever charged.

The IG report provides yet another disturbing example of an FBI and DOJ that have abused their powers in chilling ways.

Kash Patel, a man who has exposed that abuse and apparently been a victim of it, and Attorney General-designate Pam Bondi, will have their work cut out for them reforming a national security and law enforcement apparatus that all too often has undermined Americans’ rights rather than defending them.

Ben Weingarten is editor at large for RealClearInvestigations. He is a senior contributor to The Federalist, columnist at Newsweek, and a contributor to the New York Post and Epoch Times, among other publications. Subscribe to his newsletter at weingarten.substack.com, and follow him on Twitter: @bhweingarten.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News