We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

2020 was our annus horriiolis. The pandemic, the George Floyd riots. Creeping tyranny. The vast expansion of the censorship regime. Election rigging, at the very least through Zuckerbucks, and, of course, the massive increase in murders throughout America.

Advertisement

2020 sucked, big time. So bad that it gave us Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, which while not a fate worse than death, at least a fate that made us wish for the Sweet Meteor of Death.

SMOD did not arrive, and if we are smart we can learn many lessons about how not to deal with national crises.

Link: https://t.co/rcgL9g3gl5

— Alec MacGillis (@AlecMacGillis) December 17, 2024

One lesson that we should take to heart is that kneejerk reactions to national crises are almost always bound to make things worse, and by a lot. That certainly was true for the COVID lockdown of the economy. We are all familiar with the direct effects of the lockdown–the massive shift of wealth from the middle up and the damage done to children–but we are still coming to grips with many of the secondary effects that are not so obvious.

The Brookings Institution reveals one of the many fallouts from those lockdowns: the sudden rise in murders.

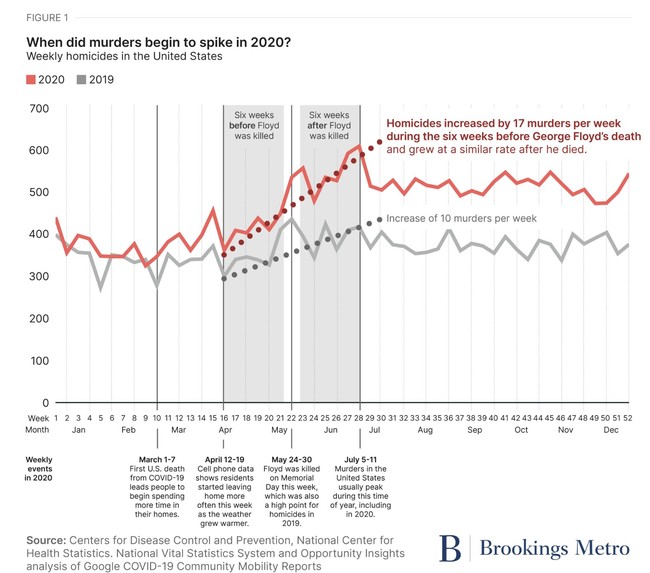

Most people would assume that the rise in murders that began in the second quarter of 2020 was caused by the fallout from the George Floyd incident, but Brookings’ study tells a much different story. The rise in the murder rate began well before the George Floyd riots, and the trajectory of the increase didn’t really change much as the riots and social discord gained steam.

In 2020, the average U.S. city experienced a surge in its homicide rate of almost 30%—the fastest spike ever recorded in the country. Across the nation, more than 24,000 people were killed compared to around 19,000 the year before.

Homicides remained high in 2021 and 2022, but in 2023 they began to fall rapidly. Projections suggest the national homicide rate in 2024 is on track to return to levels close to those recorded in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet that spike in murders continues to deliver major costs in terms of the lives lost, the people incarcerated, and the perception of decreased safety across the country.

Some commentators have suggested the increase in homicides during 2020 was a response to the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May of that year. Others hypothesized that it was caused by a police “pull back,” in which officers chose to do less work in reaction to the protests that followed Floyd’s death.

As more information has become available, these theories appear to be less supported by evidence than some initially thought.1 The evidence indicates that the national homicide rate was already on track to reach a peak far above the previous year even before Floyd was killed.

Advertisement

This may seem counterintuitive for many reasons. How can pandemic policies cause such a huge spike in violence compared to the George Floyd riots, but perhaps we have our chain of causality wrong on the issue. Is it possible that the pandemic lockdowns actually contributed to the violence of the riots, as people who suddenly had little to do and a lot of repressed anger latched onto the death of Floyd as an excuse to express their rage?

Cell phone data show this is when residents started leaving home more often as lockdown policies eased and the weather grew warmer. During the 6-week period from April 12 to May 23 (weeks 16 to 21 in Figure 1), homicides went up by an average of 17 murders each week.

After Floyd was killed on May 25, the national homicide rate continued to follow this trend, with additional increases during the 2 weeks around Memorial Day and the 2-week period around July 4. But even the highest point of these additional increases was less than 40 murders above the pre-existing trend. While it’s true that homicides did temporarily rise more than they were already on track to following Floyd’s death, these additional increases are unlikely to explain the 5,000 additional murders seen during the year.

This leaves us with a question: What happened that could have caused homicides to spike in 2020, remain high for 2 years, and then start to decline rapidly in 2023?

New data offers a potential explanation. In this report, we analyze thousands of police records and compare them to changes that occurred in U.S. cities just before homicides started to surge. This showed that the spike in murders during 2020 was directly connected to local unemployment and school closures in low-income areas. Cities with larger numbers of young men forced out of work and teen boys pushed out of school in low-income neighborhoods during March and early April, had greater increases in homicide from May to December that year, on average. The persistence of these changes can also explain why murders remained high in 2021 and 2022 and then fell in late 2023 and 2024.

Advertisement

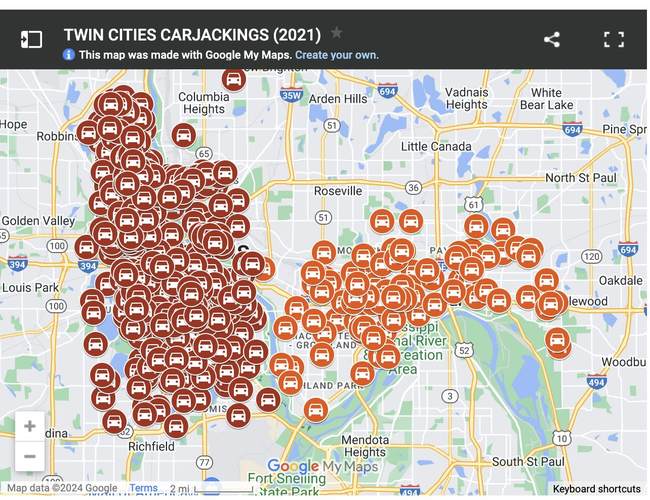

This is consistent with other trends, such as the major spike of carjackings committed by teens–often as young as 12–who were out of school and at wit’s end and unsupervised. In Minneapolis, carjackings were so few before the pandemic that statistics weren’t even kept. During and for a while after the pandemic they were rising so fast that a new category of crime statistics was created.

In 2021, the City of Minneapolis averaged two carjackings a day.

Kids who are out of school find ways to fill their time, and for young men from poorer neighborhoods one common way to do so is to engage in crime.

Kids who are out of school find ways to fill their time, and for young men from poorer neighborhoods one common way to do so is to engage in crime.

Studies suggest there are three characteristics that set people engaged in violence apart.

- Most are teenage boys and young men in their twenties. Males under the age of 30 commit more than half of all murders in the United States.

- They are more likely to be high school dropouts. Estimates suggest that around 40% of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons did not graduate from high school or earn a GED, compared to about 9 percent of all adults in the country.

- They are more likely to be unemployed. Studies have found that more than one-third of people who are incarcerated did not have a job at the time their crime was committed. This is 3 times higher than the rate for all men between the ages of 25 and 54.

Research also helps explain why the teen boys and young men who engage in violence would have difficulty completing high school and joining the workforce. People who become involved in violence have often been victims of violence themselves, are more likely to have been abused when they were children, and have higher rates of mental health issues. Due to these challenges, it is not surprising that they also have greater levels of alcohol and drug abuse.

Advertisement

The laser focus on doing SOMETHING to address the COVID pandemic–even things that had limited to no actual benefit in disease reduction–blinded policymakers to the second-order effects of their policy choices.

Public Health officials such as Francis Collins have “admitted” that he and his colleagues didn’t really consider those second-order effects because they were laser-focused on saving lives, and that perhaps that was a mistake. But that just demonstrates that they sucked at doing public health in the first place.

Even the most modest knowledge about public health ethics warns officials that the unintended consequences of coercive policies on society can turn out to be worse than the problem they are trying to solve. The job of officials is to inform and recommend to citizens more than to impose policies, and that potential unintended consequences ensure that there are landmines everywhere.

Smarter minds, such as Jay Bhattacharya, warned that this was the case, as did Marty Makery and others, but they were vilified as granny killers.

But, of course, that was nonsense. Their goal was to both save lives and save society.

You can’t upend the social order without paying a high price. And that isn’t just true for pandemic policies; it applies to CRT, climate policies, and Alphabet ideology too.

Advertisement

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News