We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

A Senate Budget Committee hearing Wednesday revisited the topic of a so-called “climate-driven insurance crisis.” The hearing was the second look at this issue. While homeowners are facing real problems with rising premiums and loss of coverage, some experts dispute the industry’s argument that climate change is playing a significant role.

In conjunction with the hearing, the committee released a report, “Uncovering the Economic Costs of Climate Change.” The report claims that a wide range of experts, from insurance industry analysts to actuaries, claim that climate change poses dangerous risks to the economy and the financial system, while also imposing “substantial costs” on American families.

“Economic damages from climate change are already occurring. As families, communities, local and state governments, and the federal budget all face this costly reality, it is no longer a question of whether, but of how bad,” the report states.

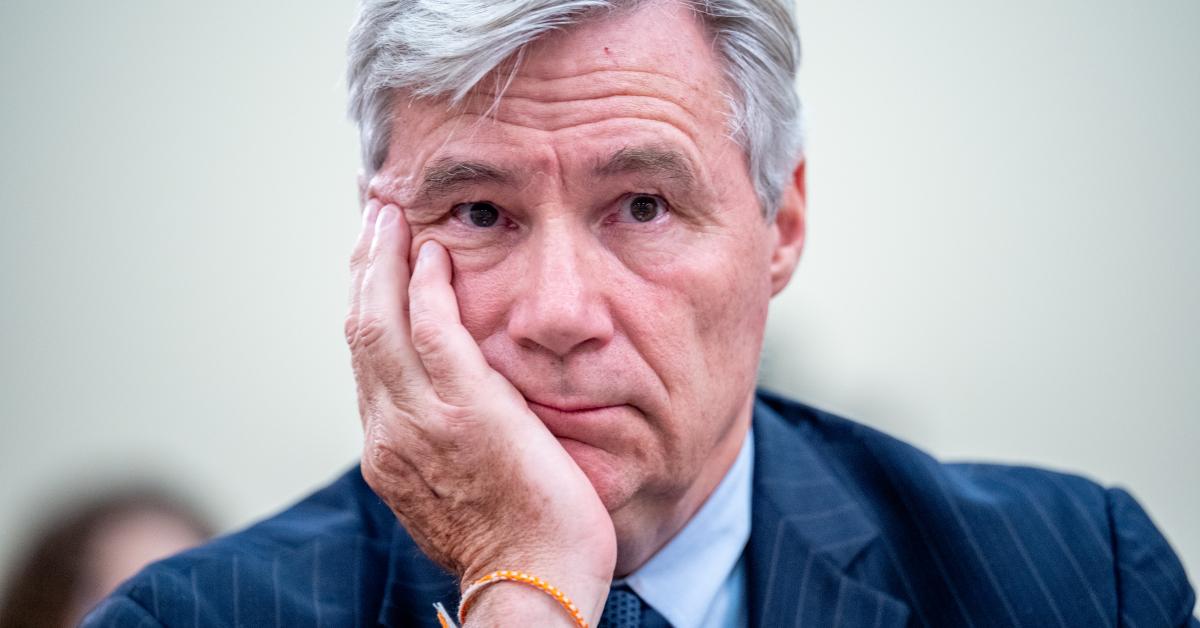

During his opening remarks at Wednesday’s hearing, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., chair of the committee, said that a letter from National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) warned that the committee’s report had some inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

The letter, according to Whitehouse, didn’t provide any specifics, but he entered it into the record and said he would follow up with NAICs to get more information. He said the committee report was based on data from 23 insurance companies, none of which voiced any concerns about the data, but he’d make corrections to the report if needed.

“I have confidence in the data, and if it turns out that there are inconsistencies or inaccuracies that we need to adjust for, we will then do so,” Whitehouse said.

Data insecurity

Among the sources the report uses to defend its conclusions is the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s “Billion Dollar Disaster” tally. Dr. Roger Pielke, Jr., retired professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder, published a study in June raising a number of issues with the “scientific integrity” of the NOAA’s tally. The following August, NOAA appeared to concede many of Pielke’s points, saying it “will take actions to improve the documentation and transparency of the data set for greater compliance with NOAA’s Information Quality Guidelines.”

Among the problems with NOAA’s tally, according to Pielke, is that it fails to normalize costs. Pielke has done extensive research spanning nearly three decades into the trends of disaster costs over time, which show the trends as a share of GDP are actually declining.

His research normalizes the disaster costs, which means he adjusts for differences in wealth over time. Pielke explains why this is important in an article on his “The Honest Broker” Substack. If a category 3 hurricane hit Miami Beach in 1926, it would impact far less development than a storm of equal intensity hitting the beach today. Without controlling for these differences, Pielke writes, it’s impossible to reliably determine trends in damages.

This was also a point in a report published in June by Chris Martz, a meteorology senior at Millersville University.

“Thus, the increase in storm damage over the last two decades is more appropriately linked to the fact that there is simply more ‘stuff’ to destroy now, as humans continue to place an ever-increasing amount of wealth in Mother Nature’s destructive path,” Martz explained in more layman’s terms. His report cites Pielke’s research.

Heartland Institute energy research fellow Linnea Lueken Thursday took the Washington Post to task for a column blaming wildfires and floods — supposedly increasing as a result of climate change — for difficulties homeowners have getting insurance. Lueken explained on Climate Realism Weekly, a publication of the Heartland Institute, that wildfires in the U.S. are up only slightly since the 1980s, and the cost of flood damage in the U.S. as a share of GDP is down significantly over the past 116 years, with no recent increases.

Lueken also pointed out that government subsidizing of insurance for homes in disaster-prone areas, such as on beaches, increases the number of people building homes in these areas. In turn, this increases the costs of damages that insurance companies are covering.

Climate risk areas

While the role climate change plays is disputed, the problems in the insurance industry are real.

The panel of witnesses at Wednesday’s hearing included Dr. Benjamin Keys, professor of real estate and finance at the University of Pennsylvania. Keys testified that premiums across the U.S. are rapidly increasing.

“We attribute this increase to a combination of inflation and financial frictions associated with the pass through of rising reinsurance costs to homeowners policies,” Keys said, adding that some of the largest insurance companies have exited markets because they can’t charge premiums that adequately reflect the growing risk.

The finance professor said that the premiums were especially high in “climate risk areas,” which are areas prone to climate-related disasters, such as coastal regions. It wasn’t clear from Keys data that trends in extreme weather from climate change were the cause of the increases.

Keys also cited data showing that 1.9 million policies were not renewed between 2018 and 2023, meaning there were 1.9 million times a household had to find a new insurer, likely at a higher premium. If those rates would have stayed at 2020 levels, Keys said, there would have been 423,000 fewer non-renewals.

“When fewer insurers do business in a market as we see now, this reduces the options available to homeowners and their ability to shop for the best rate,” Keys said.

The testimony of Dr. Robert Hartwig, clinical associate professor of finance at the University of South Carolina, provided a very different picture of what’s happening in the insurance industry.

“Let me get straight to the point — the insurance industry is not in the midst of a climate-driven crisis, nor is it about to fall. Strength and stability are the hallmarks of this industry,” Hartwig said.

Hartwig said a recent report from AM Best, the largest insurance rating agency in the U.S., found that the cumulative impairment rate, which is how the industry refers to insolvency, of AM Best-rated insurers over any 15 year period from 2001 through 23 was 0.3%, which was down significantly from the 3.9% over the 1977 to 2001 period.

“In other words, there is no evidence that the industry is on the precipice of collapse, despite material increases and insured losses arising from natural disasters over the past quarter century,” Hartwig said.

Lack of skepticism

Martz, the Millersville senior, told Just the News that there was a lot of irony in the lack of scrutiny in the legacy media and among the public over the climate change narrative coming from insurance companies.

“When you talk to climate alarmists, they always talk about how oil companies are evil and greedy,” he said, but when it comes to the “climate-driven insurance crisis,” any possible financial incentives insurance companies might have in blaming climate change for rising premiums and canceled policies aren’t given the same skepticism.

The willingness to accept the narrative also contrasts with public reaction to the recent murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. A recent poll found that 41% of young voters considered the murder acceptable.

While it’s good that the same level of animosity and distrust isn’t directed at homeowners insurance companies, both industries have the same financial incentives.

“It’s a marketing scheme, and every company is going to be guilty of doing that,” Martz said.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News