We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Gary Fladro, a Caltech graduate student working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1965, conceived the idea for “The Grand Tour” of the solar system’s outer planets.

Advertisement

The idea was to fly a spacecraft to Jupiter and use the immense gravity of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus to slingshot the probe all the way to Neptune. It would be far cheaper and take much less time for a “Grand Tour” than launching individual probes to each planet.

The biggest problem for NASA was that the proper alignment of the outer planets only happens once every couple of hundred years. The next window required a liftoff in 1977. The space agency tasked JPL with the project, and the brainiacs at the lab got to work.

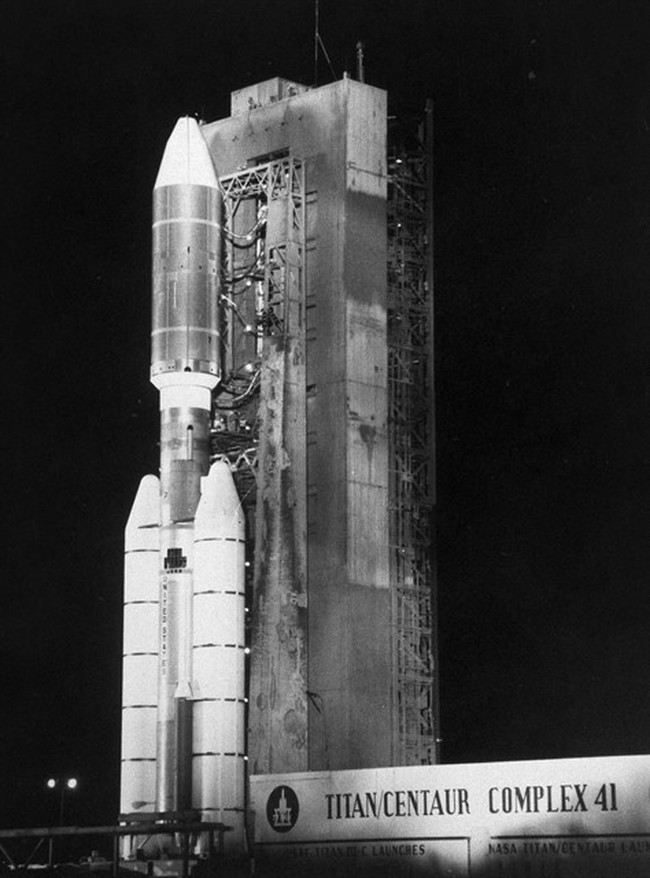

It wasn’t going to be cheap. The project cost between $750 and $900 million. Voyager 2 launched first and would visit both Jupiter and Saturn while detouring to make a close fly-by of Saturn’s huge moon Titan. Voyager 1 went on from Saturn to Uranus and Neptune.

Both spacecraft went off on parabolic courses that would eventually take them completely out of the solar system. That was 47 years ago. The probes are now 15 billion miles from Earth, far beyond the influence of the Sun and still sending back important scientific data.

Once the Voyagers’ tour of the four planets was complete in 1990, the world’s attention faded; but the probes continued to provide remarkable insights into the dynamics of the solar system, including ultraviolet sources among the stars and the boundary between the sun’s influence and interstellar space. Even today, both probes continue sending back data about the interstellar medium, the space between the stars, says Linda Spilker, NASA’s project scientist for the Voyager missions—including precise measurements of the density and temperature of the thin ionized gases it contains and the incidence of high-energy cosmic rays.

Advertisement

All good things must come to an end, and the Voyagers are nearing completion of their epic journey. Both spacecraft are powered by the heat from decaying plutonium (radioisotope thermoelectric generators or (RTGs). That power source is finally ebbing.

In October, Voyager 1 was ordered to turn on a heater to keep one of its four working scientific instruments from freezing up. The signal took 22.5 hours at the speed of light to reach the spacecraft. When the expected response 22.5 hours later didn’t materialize, the scientists knew they were in big trouble. After a frantic investigation, the scientists were able to figure out that the probe had automatically switched from its normal x-band transmitter to a much weaker s-band transmitter that hadn’t been used since the 1980s.

The probe autonomously made the transmitter swap when its computer determined that Voyager I had too little power after the mission team sent a command to turn on one of its heaters.

The unexpected change prevented engineers from being able to receive information about Voyager 1’s status, as well as the scientific data collected by the spacecraft’s instruments, for nearly a month.

After some clever problem-solving, the team was able to switch Voyager 1 back to its X-band radio transmitter and receive its daily stream of data again starting in mid-November.

Advertisement

“The probes were never really designed to be operated like this and the team is learning new things day by day,” said Kareem Badaruddin, Voyager mission manager at NASA’s JPL. “Thankfully they were able to recover from this issue and learned some things.”

One of the things they learned is that the RTGs are on the edge of failing. The scientific instruments they are powering will probably stop transmitting sometime next year, although the spacecraft may be able to provide enough power to return engineering data until 2036.

Considering the incredible science these two probes returned to Earth in their travels, a hearty “well done” is in order.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News