We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Historical revisionists have recently disparaged the righteousness of America’s role in World War II, overlooking that the fact the conflict was both a defensive war and a crusade for the liberation of oppressed peoples. We Americans are justified in celebrating it as “The Good War” fought by the Greatest Generation this country has ever produced.

It’s easy to laugh at the shadows when the night has passed. —Anonymous

“You’re under German occupation for four years. It’s horrible. And you see paratroopers come out of the sky on a Sunday morning. Who are they? They’re angels.” —William “Wild Bill” Guarnere, Company E, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne

Darrick Taylor recently penned for Crisis magazine a deeply problematic essay entitled, “’They Died for Nothing’: America and the Myth of World War II,” in which he questions Americans’ remembrance of the great conflict of 1939-1945. Beginning by noting that some World War II veterans, including his own grandfather—who late in life lamented that his comrades “died for nothing”—have, quite understandably, expressed distress about the political and cultural conditions of modern America, Mr. Taylor launches into an indictment of those who choose to remember the war as a righteous cause between good and evil.

Writing in June 2024, Mr. Taylor writes in reference to recent political events:

What, then, did those men die for on Omaha Beach, in Okinawa, in the Ardennes Forest? When those who burned whole neighborhoods to the ground go largely unpunished; while protestors who did little more than stroll through the Congressional building are imprisoned for years on end; or when one party weaponizes the legal system to keep a presidential candidate from the opposing party from running for office, you can see why my grandfather thought his comrades sacrificed their lives in vain.

It’s understandable that our beloved, aged World War II veterans might now question their own and their comrades’ sacrifice and wonder what has become of their country, now so obviously crumbling morally and socially. This is human nature. Though I miss deeply my own father, a World War II hero, I too am sometimes glad that he didn’t live to see what has become of the United States of America. But these feelings should in no way should lead us to fall into the trap of consequentialism, drawing conclusions about the worthiness of the cause of 1941-1945 simply because American democracy has, in some respects, gone awry.

“The transformations of American life that make World War II veterans feel their sacrifices were in vain originated with the war itself,” Mr. Taylor writes. “That war turned the United States from a republican, continental empire into a global, liberal one.” To attribute this development to World War II alone is a debatable point; one could make a case that previous wars—World War I, the Spanish-American War, the Mexican War—put America on a path to empire. And in considering Mr. Taylor’s broader indictment of the nascent liberal order of the United States, we may fairly may wonder what guided America in avoiding the path of despotism during the crisis of the Great Depression of the 1930s? Christianity? But Germany and Italy too were Christian nations. Is it a stretch to say that America’s political and constitutional democratic order had something to do with it?

In his indictment of the supposed liberal, globalist goals of the Allied leadership, Mr. Taylor wishes to play down the moral righteousness of the Allied cause itself:

The U.S. and its allies committed horrible acts that tend to get airbrushed out of the story: the firebombing of Tokyo and Dresden, the use of the atom bomb on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, not to mention the internment of ethnic Japanese citizens on the home front. All these violated principles which the Western Allies went to war to defend.

Yes, we can debate the morality of the Allied attacks on Tokyo and Dresden and the American government’s dropping of atomic bombs on Japan. But these were not gratuitous acts meant to slaughter civilians, but operations meant to strike at the heart of the enemies’ war machine and to bring the war to an earlier end. As to the Japanese internment camps, it must be remembered that there were spies living among the Japanese population.

American soldiers did not make war on civilians as a matter of policy. In fact, both German soldiers and civilians viewed the Americans as merciful conquerors; in the closing days of the war, the former scrambled to surrender to the Americans lest they fall into the clutches of the vengeful Russians. A veteran of the Army’s 17th Airborne Division paratrooper recalled how on one occasion his commanding officer made him return a pet rabbit to a Germany family that the soldier and his buddies intended to cook for dinner.

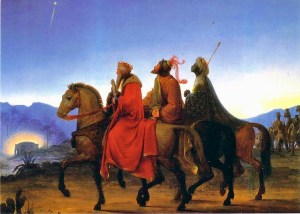

Left out of Mr. Taylor’s analysis is any mention of Nazi concentration camps, many of which were liberated by American soldiers, the brutality of the SS soldiers who murdered captured and wounded American soldiers as a matter of course, the casual slaughtering of Belgian civilians (and others) by the Nazis, or of the suffering of Nazi-occupied nations like Poland and Holland. When the American army came at last, the captive nations of Western Europe eagerly welcomed American soldiers like the liberators they were—”angels,” as Bill Guarnere of the famed 101st Airborne Division put it.

But Mr. Taylor can’t help denigrating the importance of the American soldier’s efforts: “The Western Allies’ D-Day heroics notwithstanding, it was the Red Army that defeated the Nazis, not the Americans.” I’ll be generous and call this a highly questionable claim at best, and one that was at the heart of Soviet propagandizing about “The Great Patriotic War” (though even Josef Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev knew better, at least in terms of acknowledging the material aid provided by the West). The West’s unsavory alliance with the tyrannical Stalin was an unfortunate necessity, as it took both East and West to defeat the formidable Nazi war machine. And the truth is that Hitler’s forces nearly won the war despite the participation of the American army in the conflict.

Taylor here simply falls into the trap of reading history backwards. Counter-history is a dangerous enterprise, but we can reasonably ask what would have happened had the D-Day landings failed—an outcome that analysts at the time and Dwight Eisenhower feared greatly, and one that historians today consider as likely as not. We also forget now that the mighty Battle of the Bulge of the winter of 1944-45, which resulted from Hitler’s attempt to break through encircling Allied forces and reach the strategically critical port of Antwerp, was nearly successful. And if the Germans had succeeded in this campaign, there is a good chance that they too would have defeated the Soviets on their eastern front and won the war. Despite Mr. Taylor’s haughty eagerness to “correct” those poor naifs he encounters today who believe so, we Americans might indeed have been speaking German today had the Nazis won World War II.

And, returning to the righteousness of the American cause, it was important that the Red Army did not single-handedly defeat the Nazis, even if we allow Mr. Taylor’s dubious claim that it could have. What would Europe have looked like with the Soviet Union winning the war on her own? We know well the extent of the suffering of those who lived under communist rule for the duration of the Cold War, which had already begun as the hot war raged. In the war’s closing days, American forces, some led by the famously anti-Russian General George S. Patton, barreled east in an attempt to limit Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe and ensure that as many Europeans as possible would live freely under the new Pax Americana and not simply trade fascist tyranny for the communist brand; sadly, the peoples of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and elsewhere would do just that.

Not content to indict the Allied war effort, Mr. Taylor is eager also to disparage the heroism of World War II soldiers, pooh-poohing the idea of “the Greatest Generation” that Americans unthinkingly hold in “reverential awe.” His distaste for this patriotic admiration is palpable. He unabashedly asserts of American GI’s, “mostly their wish was that of all soldiers in war time: to get back home.” Of course, soldiers always want to go home, but as was certainly the case among the vast majority of World War II soldiers, only when their “job is done,” as many put it. There are numerous accounts of teenage (and pre-teen!) American boys in the 1940s lying about their age in order to enlist in the armed forces, of volunteers rejected for enlistment because of physical shortcomings who committed suicide as a result, and of many veteran soldiers who resisted going home despite serious wounds that would have entitled them to do so. Indeed, many, like Bill Guarnere, tried to disguise the severity of their wounds so as to rejoin their units sooner. World War II soldiers didn’t fear the enemy as much as they feared failing to do their duty. They were a special breed, one that veterans of later wars have told me they hold in special esteem… or as one might say, “reverential awe.”

In evaluating the righteousness of the United States’ role in World War II, Darrick Taylor, like other revisionist critics, seem to forget this most obvious fact: Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (a fact that led many Americans to hold the Japanese in special contempt and that had nothing to do with their ethnicity), and Germany subsequently declared war on our country. From the American perspective then, World War II was at heart a defensive war. But it also became a war for the liberation of oppressed peoples and the promulgation of liberty, and in all these senses, it constitutes a just and righteous cause. We Americans are justified, then, in celebrating World War II as “The Good War” fought by the Greatest Generation this country has ever produced.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photograph, “General Dwight D. Eisenhower addresses American paratroopers prior to D-Day,” and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News