We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

When your bird reaches the table this Thursday, you can ask your table mates if they know why the bird is called a turkey, and then—if you have read this essay—impress them with your encyclopedic knowledge.

You remember the Dad joke at this time of year: “We’re having an international Thanksgiving. Mom’s serving Turkey on her best china.” It turns out that the turkey is a more cosmopolitan bird than we first knew. A look at the derivation of the name reveals a truly international origin of the traditional Thanksgiving sacrifice.

You remember the Dad joke at this time of year: “We’re having an international Thanksgiving. Mom’s serving Turkey on her best china.” It turns out that the turkey is a more cosmopolitan bird than we first knew. A look at the derivation of the name reveals a truly international origin of the traditional Thanksgiving sacrifice.

Why do we call that big bird a “turkey” Did they originate in Turkey? Do they have anything to do with Turkish delight, Turkish carpets? Turkish cigarettes? Ornithologists disagree about the bird’s origins, but wild turkeys were probably first domesticated in Mexico around 800 BC. The ocellated turkey has a plumage display similar to peacocks, and historians report that Mayan aristocrats and priests had a special regard for them. Spanish chroniclers describe the multitude of food that was offered in the vast markets of Tenochtitlán, noting there were tamales made of turkeys, iguanas, chocolate, vegetables, fruits, and more.

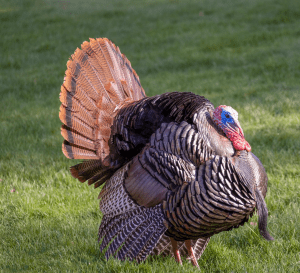

By the way, the fleshy protuberance under the male turkey’s beak is called his “snood.” Like the peacock, the male fans out his tail feathers as part of the mating ritual. His snood is also enlarged, and the more impressive the fan, and the bigger the snood, the more attractive he is to the female.

Wild turkeys migrated north to the American Southwest and were probably domesticated by the indigenous peoples there, but the way turkeys made their way to Europe gives us the bird’s name. The first turkeys were imported by the Spanish around 1519, and it is generally accepted that the first turkey was introduced to Britain in 1526 by William Strickland of Yorkshire. Strickland sailed to North America with Sebastian Cabot, but it is unclear whether he obtained the bird in his North American adventure, or from Spanish traders. Strickland’s family crest, designed in 1550, features a large turkey in full feathery display. Strickland was a feisty Puritan politician during the Elizabethan regime and wished to make the turkey his claim to fame.

Did you think Benjamin Franklin really wanted the turkey as the American national bird? Not quite. In a private letter Franklin expressed his dislike for the eagle which he considered a “cowardly bird” and his admiration for the turkey, which “would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.”

There are two possible explanations for the turkey’s name. One theory proposes that when Europeans first encountered turkeys in the Americas, they incorrectly identified the birds as a type of guineafowl, which were already being imported into Europe from the Far East through Constantinople. Thus the name “turkey coqs.” The name of the North American bird may have then become “turkey fowl” or “Indian turkeys… and eventually just “turkeys.”

The other theory suggests that the turkeys were coming to England not directly on transatlantic shipping but via the Middle East, where the birds had been imported and domesticated. Again the Turkish importers lent the name to the bird, and “turkey cocks” was soon shortened to “turkeys.”

By 160o the turkey cock was well known enough in England to make it into Shakespeare. In Henry V, Gower says, “and here he comes swelling like a turkey cock,” and in Twelfth Night (written a year later), while watching the prank played on Malvolio, Fabian compares his strutting to the bird that was now well known as a competitor to the peacock: “O, peace!” Fabian cries, “Contemplation makes a rare turkey-cock of him: how he jets under his advanced plumes!”

An Eastern origin for the turkey is echoed in other European languages. The French refer to the Thanksgiving fowl as dinde (‘from India’) Russians call it indyushka, ‘bird of India,’ while Poles and Ukrainians call it indyk and in Turkish, hindi. The Indian reference goes back either to the belief that Columbus sailed to India rather than the Americas, or that the native Americans were “Indians.” In Portuguese a turkey is a peru—again, perhaps linking the bird to South America.

So when your bird reaches the table this Thursday, you can ask your table mates if they know why the bird is called a turkey, and then impress them with your encyclopedic knowledge… in order to avoid controversial conversations about politics.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News