We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

During his November 1 Friday mosque sermon at the North Hudson Islamic Center in New Jersey, CAIR official Ayman Aishat made a seemingly starting claim:

We live in America, the United States of America. Brothers and sisters, those who do not know history, not too long ago, the USA was paying the jizya to the Ottoman Caliph.

Could this be?

First, let us define jizya. In brief, it is the monetary tribute that conquered or cowed infidels pay their Islamic overlords in exchange for peace, according to Koran 9:29:

Fight those among the People of the Book [Christians and Jews] who do not believe in Allah, nor the Last Day, nor forbid what Allah and his Messenger have forbidden, nor embrace the religion of truth [Islam], until they pay the jizya with willing submission and feel themselves subdued.

And yes, Aishat is correct: once upon a time, in its fledgling youth, the United States succumbed to paying jizya to appease Muslim terrorists. That story is instructive — not least as it includes the genesis of the U.S. Navy.

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the Muslims of North Africa (“Barbary”) thrived on enslaving Europeans. According to the conservative estimate of American professor Robert Davis, “between 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly a million and quite possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast.” (With countless European women selling for the price of an onion, little wonder by the late 1700s, European observers noted how “the inhabitants of Algiers have a rather white complexion.”)

As Barbary slaving was a seafaring venture, nearly no part of Europe was untouched. From 1627 to 1633, Lundy, an island off the west coast of Britain, was actually occupied by the pirates, whence they pillaged England at will. In 1627 they raided Denmark and even far-off Iceland, hauling a total of some 800 slaves.

Such raids were accompanied by the trademark hate. One English captive writing around 1614 noted that the Muslim pirates “abhor the ringing of the [church] bells being contrary to their Prophet’s command,” and so destroyed them whenever they could. In 1631, nearly the entire fishing village of Baltimore in Ireland was raided and “237 persons, men, women, and children, even those in the cradle” seized.

By the late eighteenth century, Barbary’s strength relative to Europe had plummeted, and the Muslims could no longer raid the European coastline for slaves — certainly not on the scale of previous centuries — so its full energy was spent on raiding non-Muslim merchant vessels. European powers responded by buying peace through tribute, which the Muslims accepted as jizya.

By the late eighteenth century, Barbary’s strength relative to Europe had plummeted, and the Muslims could no longer raid the European coastline for slaves — certainly not on the scale of previous centuries — so its full energy was spent on raiding non-Muslim merchant vessels. European powers responded by buying peace through tribute, which the Muslims accepted as jizya.

Fresh and fair meat appeared on the horizon once the newly-born United States broke free of Great Britain and was therefore no longer protected by the latter’s jizya payments. In 1785 Muslim pirates from Algiers captured two American vessels, the Maria and Dauphin; they enslaved and paraded the sailors through the streets to jeers and whistles. Considering the horrific ways Christian slaves were treated in Barbary — sadistically tortured, pressured to convert, and sodomized, as described in the writings of missionaries, redeemers, and others (e.g., John Foxe, Fr. Dan, Fr. Jerome Maurand, Robert Playfair) — when the Dauphin’s Captain O’Brian later wrote to Thomas Jefferson that “our sufferings are beyond our expression or your conception,” he was not exaggerating.

Jefferson and John Adams, then ambassadors to France and England respectively, met with Tripoli’s ambassador to Britain, Abdul Rahman Adja, in an effort to ransom the enslaved Americans and establish peaceful relations. In a letter to Congress dated March 28, 1786, the hitherto puzzled American ambassadors laid out the source of the Barbary’s unprovoked animosity:

We took the liberty to make some inquiries concerning the grounds of their pretentions to make war upon nations who had done them no injury, and observed that we considered all mankind as our friends who had done us no wrong, nor had given us any provocation. The ambassador answered us that it was founded on the laws of their Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that all nations who should not have acknowledged their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as prisoners, and that every Musselman who should be slain in battle was sure to go to Paradise.

This, of course, was a paraphrase of Islam’s so-called “Sword Verse” (Koran 9:5), which ISIS invoked earlier this year.

At any rate, the ransom demanded to release the American sailors was over fifteen times greater than what Congress had approved, and little came of the meeting.

Back in Congress, some agreed with Jefferson that “it will be more easy to raise ships and men to fight these pirates into reason, than money to bribe them.” In a letter to a friend, George Washington wondered:

In such an enlightened, in such a liberal age, how is it possible that the great maritime powers of Europe should submit to pay an annual tribute to the little piratical States of Barbary? Would to Heaven we had a navy able to reform those enemies to mankind, or crush them into nonexistence.

But the majority of Congress agreed with John Adams: “We ought not to fight them at all unless we determine to fight them forever.” Considering the perpetual, existential nature of Islamic hostility, Adams was probably more right than he knew.

Congress settled on emulating the Europeans and paying off the terrorists, though it would take years to raise the demanded ransom. In 1794 Algerian pirates captured eleven more American merchant vessels.

Two things resulted: the Naval Act of 1794 was passed, and a permanent standing U.S. naval force was established. But because the first war vessels would not be ready until 1800, American jizya payments — which took up 16 percent of the entire federal budget — began to be made to Algeria in 1795. In return, some 115 American sailors were released, and the Islamic sea raids formally ceased.

American jizya and “gifts” over the following years caused the increasingly emboldened pirates to respond with increasingly capricious demands.

One of the more ignoble instances occurred in 1800, when Captain William Bainbridge of the George Washington sailed to the Dey of Algiers (an Ottoman honorific for the pirate lords of Barbary), with what the latter deemed insufficient tribute. Referring to the American crew as “my slaves,” Dey Mustapha proceeded to order Bainbridge to transport the Muslim’s own annual tribute — hundreds of black slaves and exotic animals — to the Ottoman sultan in Constantinople (Istanbul).

Adding insult to insult, the Dey commanded the U.S. flag taken down from the George Washington and the Islamic flag hoisted in its place; and, no matter how rough the seas might be during the long voyage, Bainbridge was ordered to make sure the vessel faced Mecca five times a day for the prayers of Mustapha’s ambassador and entourage. Bainbridge condescended to being the Muslim pirate’s delivery boy.

Soon after Jefferson became president in 1801, Tripoli demanded another, especially exorbitant payment, followed by an increase in annual payments — or else. “I know,” Jefferson concluded, “that nothing will stop the eternal increase of demand from these pirates but the presence of an armed force.” So he refused the ultimatum, and, on May 10, 1801, the pasha of Tripoli, having not received his timely jizya installment proclaimed jihad on the United States.

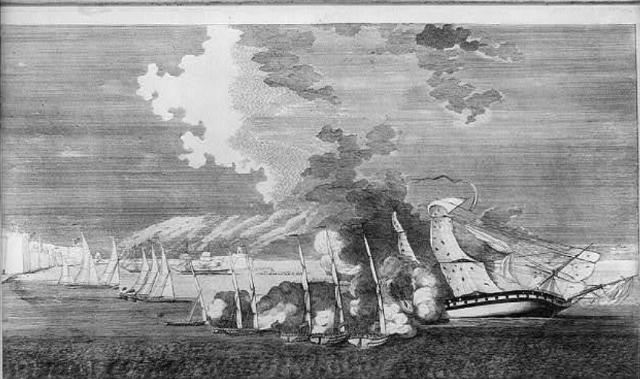

Thus began the United States’ first war as a nation, the First Barbary War (1801-1805).

But that is another story.

Raymond Ibrahim, author of Defenders of the West and Sword and Scimitar, is the Distinguished Senior Shillman Fellow at the Gatestone Institute and the Judith Rosen Friedman Fellow at the Middle East Forum.

Image: Public Domain

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News