We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

It’s October, and the urge for theatrical, spooky music always arises for me right about this time. Cue a visit to the essay I wrote years back, “Ten Spooky Classical Faves for Halloween.” Each year, it seems, I have a different relationship with the music and its composers. This year, I’m taking a particular interest in Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, a tone-poem depiction of a witches’ sabbath that draws from Russian folklore. It’s turbulent, troubling, dramatic, and spicy, which also sort of describes Modest Mussorgsky himself, certainly in the second half of his life. It’s fascinating to consider, then, that he came into the world amid genteel, prosperous circumstances. Born March 21, 1839 in Karevo, a village in the Russian province of Pskov, he was raised on a big estate, trained in the most proper of ways. His father, a lover of music, allowed his son to dabble in music—the boy was prodigiously good at the piano—but nonetheless he was sent to cadet school in anticipation of a career as a military officer.

Upon completion of his education, Modest was every inch the polished young officer, popular with his peers, impressing the ladies, fond of drink and nights of reveling, where he liked to show off his skills on the piano to further impress the ladies. Alexander Borodin, also a young army officer (whose destiny would intertwine with Modest’s for decades as members of Russia’s Group of Five), met Modest around this time and described him thus:

He was at that time a very callow, most elegant, perfectly contrived little officer: brand-new, close-fitting uniform, toes well turned out, hair well-oiled and carefully smoothed-out, hands shapely and well cared for. His manners were polished and aristocratic. He spoke through his teeth, and his carefully chosen words were interspersed with French phrases. He showed signs of a slight pretentiousness, but also, quite unmistakably, of perfect breeding and education. He sat down at the piano and, coquettishly raising his hands, started playing delicately and gracefully, bit of Travatore and Traviata, the circle around him rapturously murmuring, “Charmant! Délicieux!”

That Modest looked like this:

A few words about the aforementioned Group of Five in regard to nineteenth-century Russian classical music: At that time, the Westernized aesthetic heavily prevailed over the scene. Which meant the sound of Italian opera, German Romanticism, precisely constructed operas, symphonies, sonatas, concertos, chamber pieces, etc. The idea of a country’s nationalism, its pride in its traditions and culture being reflected in its music, was a situation just starting to take hold on the periphery of mainstream European classical music. Think Hungary, Bohemia, Spain, Poland. And now, Russia, beginning with Mikhail Glinka and his 1836 opera, A Life for the Czar. This was a big deal, you see, because up to then, opera in Russia had been very Italian, sung in Italian, set in bucolic European locales. This is partly because classical music in Russia wasn’t given a lot of attention prior to this moment in time. There were no music conservatories to train fledgling musicians and composers. Music wasn’t considered art in the way painting and sculpture were, and thus received no support from the government. Glinka’s Russia-inspired opera was a hit and started the wheels of change rolling.

Fast forward twenty-one years, to Glinka’s death, when a loyal devotee, a self-taught composer named Mily Balakirev, took the helm and soon there was A Thing happening with Russia, its music now imbued with the flavors and folklore of the fatherland, thanks to a band of five composers who would gradually solidify and define the Russian national movement Glinka had started.

Around the time Mussorgsky met Borodin, he also met Mily Balakirev and César Cui, the first two members of The Five. Balakirev served as a tutor and a mentor to Modest and quickly won him over with this exciting new philosophy about “Russian” classical music. Within a year, Modest resigned his military commission and flung himself into wholeheartedly in being a composer and the third member of The Five. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov would eventually follow, as would Borodin, and there you have it: The Five (also known as “The Mighty Handful”).

Harold C. Schonberg in The Lives of the Great Composers describes the group in vivid detail:

They sat directly at Balakirev’s feet. Their curriculum and method of study would have brought tears to the eyes of a good German professor. Lacking books, lacking basic knowledge, they simply leaned on each other and on Balakirev. They would get whatever scores they could, from Bach through Berlioz and Liszt, playing through them, analyzing their form, taking the pieces apart and putting them together again. Perhaps that is not a bad way to study music. They criticized one another’s works, helped one another compose, advanced in tiny steps. They were a close-knit group and two of them, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, actually roomed together for a while. As Borodin wrote, “In the relations within our circle, there is not a shadow of envy, conceit or selfishness. Each is made sincerely happy by the smallest success of another.”

Self-taught and proud of it, they defiantly made a virtue of their liabilities and raised the flag of their doctrine in an uncompromising manner. As a group they preached spontaneity, “truth in music,” nationalism, opposition to academism and Wagnerism. To them the villains of Russian music were the Rubenstein brothers and their conservatories, for they were the Enemy, representing the Western “learned” tradition.[…] “It would be a serious error to consider Rubinstein a Russian composer,” Cui wrote. “He is merely a Russian who composes.”

With no subsidies or support available from the Russian government, they all needed to maintain income-producing careers elsewhere. Balakirev established the Free School of Music and served as conductor for its sponsored concerts of new Russian music. Cui, as an army officer, was a fortifications engineer. Borodin was a scientist, having graduated with honors from the Academy of Medicine with a specialty in chemistry. Rimsky-Korsakov was an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy (and more; I written about him HERE). Mussorgsky came from wealth and therefore didn’t have to pursue other means of income. That is, until the Emancipation Reform of 1861 abolished serfdom throughout Russia, an edict that financially devastated the Mussorgsky family. Modest was forced to find work, like the others. Unhappy as a government clerk, composing relegated to after-hours, his drinking habit grew unmanageable, his moods darker and more depressive. His mother’s death in 1865 deeply affected him, and he only went downhill from there, his health steadily deteriorating while his drinking steadily increased. Curiously–or not–his creativity increased and he continued to produce stunning, highly original music, in truth the most talented and memorable of The Five. But his deep, lasting affection for the bottle became a losing battle and he died, a veritable wreck, at age 42. A vivid (regrettably so) portrait by Ilya Repin, painted a few weeks before Mussorgsky’s death, says it all.

Repin shared his own feelings about the decline:

It was really incredible how that well-bred Guards officer, with his beautiful and polished manners, that witty conversationalist with the ladies, that inexhaustible punster… quickly sank, sold his belongings, even his elegant clothes, and soon descended to some cheap saloons where he personified the familiar type of has-been, where this childishly happy child, with a red potato-shaped nose, was already unrecognizable.

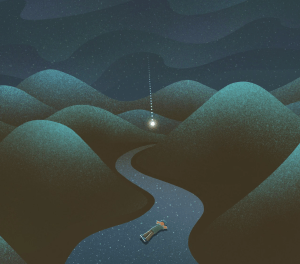

Let’s backtrack to happier times, and the genesis of Night on Bald Mountain. In 1867 when Mussorgsky was still in his twenties, he told Rimsky-Korsakov that he had completed what he called a “tone-picture” for orchestra, titled St. John’s Night on the Bare Mountain. Prior to this, he’d dabbled with other compositions—he was notorious for not completing his projects, but moving on to the next shiny new thing. First was a full-scale opera based “St. John’s Eve,” a short story by Nikolai Gogul. Second was a one-act opera based on Baron Mengden’s play, The Witches. Neither of those projects actualized, but what the two of them had in common was a spooky element that incorporated Russian folklore. Legend has it that nocturnal revels take place high on a hill in Ukraine on St. John’s Night (think Halloween-meets-St. John’s Day, a midsummer feast celebrating John the Baptist’s birth). There’s a demon named Chernobog who unleashes all sorts of horrible, evil, scary spirits. In Mussorgsky’s depiction, it’s the sound of far-off church bells, heralding dawn, that causes Chernobog to lose his powers. The bad spirits gradually disperse, and Chernobog himself melts into the top peak of the mountain (an image fabulously portrayed in Walt Disney’s Fantasia).

This, then, was what comprised St. John’s Night on the Bare Mountain and he told Rimsky-Korsakov, “Let it clearly be understood… that I shall never start remodeling it; with whatever shortcomings it is born, and with them it must live if it is to live at all.”

He was, shall we say, a touch overconfident. We all know now that Night on Bald Mountain is gripping, wildly original, and unforgettable, but back in 1867, it was Balakirev’s opinion that mattered most, and Balakirev gave the work a resounding thumbs down. So it got tucked away, never completed (although he picked it up from time to time to work on it). It was only after his death that Rimsky-Korsakov took his friend’s score and lovingly reworked its orchestration and came up with something quite nice that music critic Jan Swafford calls, “a delightful outing of mock diabolism, with whizzing violin effects for spirits, orgiastic writhings, and lots of demonically braying trombones.” And noticeably, no offense to Rimsky-Korsakov’s efforts, he said this: “What carries it, finally, is not the orchestral tricks but rather Mussorgsky’s harmonic and melodic and descriptive imagination.”

Let’s give Night on the Bald Mountain a listen. There are three versions to listen to and all three are uniquely great. We’ll begin with Leopold Stokowski’s 1940 arrangement for Disney’s Fantasia:

Now here’s Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1886 re-orchestration:

Finally, click HERE to listen to Mussorgsky’s original score, conducted by Claudio Abbado.

All right, what did you think? I have to say, watching Disney version, remembering The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (which I wrote about HERE) as being “the spooky one” (okay, only in a psychological sense; all those demon brooms multiplying freaked me out) in Fantasia, I now found myself pretty creeped out by Chernobog and his evil energy. And all those deliciously creepy spirits he calls forth. I’m wondering how many children through the ages have lain in bed, long after watching it, spooked by the images and now unable to sleep? Kudos to the Disney team on it all, especially the ending where Chernobog turns back into a mountain peak.

Second question: which one did you prefer? For me, it’s a toss-up. I just loved the last 2 ½ minutes of the Rimsky-Korsakov re-orchestration. But of course the original is thrilling to hear, because it’s pure, unfiltered Mussorgsky, in all his Russian mad-genius-ness. And the animated one tells the story so succinctly and colorfully, I kind of think I’d choose that one.

But before you decide …

There is a choral version as well, which is less Night on Bald Mountain tone-poem and more from a Mussorgsky opera. (Its official title here is “St. John’s Night on the Bare Mountain — Version for Choir and Orchestra.”) Listening to it answered questions for me as to why Rimsky-Korsakov’s arrangement had those lovely final two minutes. Turns out that when Rimsky-Korsakov re-orchestrated the original, he drew from an excerpt of Mussorgsky’s The Fair at Sorochyntsi. Composed between 1874 and 1880, the opera remained unfinished at the time of his death. It was revived and completed in subsequent years by various composers, starting with César Cui in 1917, and including the best-known version in 1931 by Vissarion Shebalin. Unfathomably, it’s a comic opera. I was not expecting that from Mussorgsky. Here it is. The really dreamy stuff Rimsky-Korsakov added to his version of Night on Bald Mountain is at 8:10.

PPS: And for even more fun, HERE is the overture to The Fair at Sorochyntsi. I’m just falling out of my chair in astonishment at its loveliness.

Happy Halloween to one and all, and if you want more spooky classical tunes, check out my essay, 10 Spooky Classical Faves for Halloween.

Republished with gracious permission from The Classical Girl (October 2024)

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Bonfire celebrating Midsummer Night” (1912/1926) by Nikolai Astrup, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The photograph of the young Mussorgsky is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The 1881 portrait of Mussorgsky by Ilya Repin is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News