We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

I don’t know about you, but I wish I had been born with the user manual for the human being or at least received instruction in school about the basic equipment every human being possesses. In my youth, I was incredibly ignorant about my senses, emotions, memory, imagination, intellect, and will. For me, it was like waking up alone, finding myself on board the space shuttle, and then through trial and error, trying to figure out how to fly the machine without much success. After a series of personal disasters that are irrelevant to report here, I was forced to write a user manual to help guide me through life. I began with what makes us human.

1. Language Makes Us Human

Wild Boy of Aveyron

In the history of science, the only event remotely akin to the philosophical concept of a person living in a state of nature, untainted by civilization was the discovery, in 1801, of the feral boy of Aveyron, an eleven-year-old found running naked and wild in a forest.[1] Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard, a French surgeon, thought the wild boy of Aveyron was the Rosetta stone for deciphering human nature. He spent five years trying to train and educate the boy, before concluding that the boy’s prolonged isolation from humanity rendered him incapable of language and consequently incapable of living a genuine human life. Itard’s answer to “What makes us human?” — language.

Helen Keller

Helen Keller gives us a glimpse of how the world is experienced without language. When she was 19 months old, an acute disease, possibly scarlet fever or meningitis, left her blind and deaf. She soon “felt the need of some communication with others and began to make crude signs. A shake of the head meant ‘No’ and a nod, ‘Yes,’ a pull meant ‘Come’ and a push ‘Go.’ Was it bread [she] wanted? Then [she] would imitate the acts of cutting the slices and buttering them.”[2]

Without language, Helen’s interior life was limited to sense perception, motor skills, tactile memory, and associations. She exercised neither will nor intellect and was “carried along to objects and acts by a certain blind natural impetus.” She felt anger, desire, and satisfaction; however, she never “loved or cared for anything.” She describes her inner life then as “a blank without past, present, or future, without hope or anticipation, without wonder or joy.”[3]

Ms. Keller recounted that the sign language she learned from Anne Sullivan “made me conscious of love, joy, and all the emotions. I was eager to know, then to understand, afterward to reflect on what I knew and understood, and the blind impetus, which had before driven me hither and thither at the dictates of my sensations, vanished forever.”[4] She no longer lived an animal life; language freed her to be human.

Through language, humans bring out the full potentiality hidden in matter, advance the building of bird nests and beaver dams to architecture and engineering, the gathering of nuts to farming, squawks and barks to music, sexual reproduction to love and compassion, and limited animal perception to the intellectual jewels of modern Western culture, Newtonian physics, Maxwell’s electrodynamics, special and general relativity, quantum physics, and the biology of the physical basis of life, including the deciphering of the genetic code.

Robert Sapolsky, a primatologist and neuroscientist, explains why nonhuman primates cannot speak. Only the brain of Homo sapiens has Broca and Wernicke areas, the regions needed for language production and comprehension, respectively. The brains of the other primates, including chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos, orangutans, and rhesus monkeys, have only the beginning of these structures, a mere cortical thickening.[5]

We Are Social by Nature

Without language, without others to learn language from, the mental capacities that Ms. Keller, you, and I were born with would not have developed, and our lives would not have been much higher than those of animals. The language my children learned at home was not unique to our family or neighborhood. Learning English in the home connected them to a larger community with much in common. Conservative estimates place the number of native speakers of English at 365 million; an additional 510 million use English as a second language; and, if a lower level of language fluency is included, then over one billion people, an eighth of the world’s population, speak English. The number of people my children can easily communicate with is staggering.

We need things that are impossible to get if we live alone; thus, by nature, we are part of a group that helps us live well. Even a recluse who retires to a remote region of Alaska to live alone brings with him knowledge and skills acquired from prior group living. In our highly technological society, no person knows how to produce everything that he or she consumes or uses in a single day. What person knows how to grow broccoli, make eyeglasses, weave cloth, generate electricity, and fabricate a microchip? The community of humans supplies all our needs. The farmer is given the fruits of ten thousand years of experimentation with the growing of crops; the poet, a language and the poetry of Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare; the physicist, the understanding of Newton, Einstein, and Bohr. No farmer, poet, or physicist could ever pay for all the gifts he or she receives gratuitously.

Our First Experience in Life

Even the newborn infant reveals the social nature of Homo sapiens. Ethologist Robert Fantz developed, in 1961, a reliable technique for measuring the visual preferences of babies. Presenting a reclining infant with two visual stimuli, he measured the amount of time each object was reflected in the infant’s pupils. In this way, Fantz was able to infer the baby’s preference for one object over another. It is now known that newborn vision is at least 20/150, an acuity not exceeded by many adults. “By demonstrating the existence of form perception in very young infants we… disproved the widely held belief that they are anatomically incapable of seeing anything but indistinct blobs of light and dark,” Fantz reports.[6]

He and many subsequent experimenters found clear evidence that babies, even those less than twenty-four hours old, prefer to gaze at a human face more than any other object, whatever its color, shape, or pattern. Other investigators have found that “the human voice, especially the higher-pitched female voice, is the most preferred auditory stimulus in young infants.”[7] These preferences are clearly not learned: in one study, the youngest babies were ten minutes old.

Fantz showed in other experiments that without learning or experience, a baby chick prefers to peck at three-dimensional, round, small objects. Nature directs the newly hatched chick to look for grain; correspondingly, as soon as the human infant emerges from the womb, it looks for a human face and listens for a soprano voice. Nature directs the infant to seek its mother.

2. We Are Meant to Love and Be Loved

Language makes us human, and love gives us existence. Without love, or desire if you like, our parents would not have coupled up, nor would we have pursued anything we thought good.

The Four Loves

In English, love is an ambiguous word that can mean sexual attraction, affection for another, or even a strong like for a particular music, sport, or food. In Koine Greek, that is Hellenistic and Biblical Greek, love is divided into four kinds, storgē, erōs, philía, and agape.[8]

Storgē

Often called familial love, Storgē is a natural affection that arises from the familiarity of persons, such as two women who daily sit next to each other on a commuter bus. The most intense form of storgē is that of a parent for an offspring; however, storgē is so broad that it even refers to the relationship between pets and their owners. In American English, the word that corresponds most closely to storgē is “affection.”

Erōs

Erōs is an intense, passionate desire to be joined to another person, to beauty, to truth, or to any good outside of oneself. As we have seen, when we emerged from the womb, we sought a human face and listened for a soprano voice. Our very first experience in life was connecting ourselves to another person. The first word spoken about us was either “boy” or “girl,” a word that drew attention to our anatomy that exhibited that we were physically incomplete but had the latent desire for a profound union with another person. As a baby, we were a lovable bundle of erōs, the natural desire for full existence. This self-love is not a selfish love, although it often becomes selfish.

In Modernity, erōs is usually taken to be romantic love as depicted by movies, magazine ads, popular songs, and romance novels. Psychoanalyst Eric Fromm describes how this all-consuming love happens: “If two people who have been strangers, as all of us are, suddenly let the wall between them break down, and feel close, feel one, this moment of oneness is one of the most exhilarating, most exciting experiences of life. It is all the more wonderful and miraculous for persons who have been shut off, isolated, without love.”[9]

Philía

Philía is usually translated as friendship, although the ancient understanding of philia is much wider, for philia holds the members of any association together, whether it be a city-state, a business partnership, or even a buyer and a seller. Philia between buyer and seller should exist before, during, and after an exchange of material goods. In capitalism, the relationship between buyer and seller is contractual. In the ancient world, no genuine community existed without philia.

In his Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that we love what is good, pleasurable, or useful about another person, and thus there are three kinds of friendship.[10] When the motive of friendship is usefulness, we do not feel affection for another as such but seek to fulfill the desire for some material good through them. These friendships are not always morally reprehensible. Many friendships of utility, for instance, are founded on the exchange of favors. These relations are common among neighbors and acquaintances and include such everyday associations as carpools and food co-ops.

Friendships based on pleasure are not that different from friendships of utility. We love witty people not for what they are but for the pleasure they give us. Children call one another friends because of the pleasure they have when playing together; yet such childhood friendships advance human growth and development.

In the third kind of friendship, based on the good, a common life is shared. Whatever makes life desirable is pursued together. Some friends engage in sports together, others perform music, others pursue social justice. Unlike erōs where lovers gaze at each other, friends under the power of philía gaze at a third thing outside of themselves. What friends love most in life is what joins them together; their mutual love enhances their love of the third thing that binds them together. Such friends feel pleasure and pain from the same things, judge the same way, and understand the same things—in a sense, they are one soul, and such unity of souls, in itself, is pleasurable.

In the truest, most long-lasting friendship, a friend acts for his friend’s good for the friend’s sake, as if his friend were another self. In this highest form of friendship, we love our friends in the same way we love ourselves. Aristotle defines the highest form of friendship as the love that wishes another everything we think good, and moreover for the other’s sake, not for our own, and to bring these goods things about for the other, as far as we can.[11]

Agápē

In the New Testament, the Gospel of Love, the Greek word erōs does not occur once, while agápē, infrequently used in ancient Greek, occurs 116 times and stands for a new understanding of love. In the King James Version of the Bible, agápē is translated as charity, a word that now means to most people giving handouts to the homeless or contributing to United Way. In the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, agápē is translated as love, an ambiguous word in English that can mean romantic love or even a strong like, say for major league baseball or Italian food.

In the Christian tradition, agápē means God’s selfless love for human persons, a love that cannot be earned and excludes no one.[12] Such love gives and expects nothing in return. God needs nothing. Since no English translation accurately renders how agápē is used in the New Testament, probably the best recourse is for the reader to stop, ignore the proper Greek, which only a minority of us know, and try substituting agápē and agápēd for “love” and “loved.” For example, John 13:34: A new commandment I give to you, that you love [agápē] one another; even as I have loved [agápēd] you, that you also love [agápē] one another.

Despite the butchering of the Greek, this substitution shows that Jesus is calling us to practice a new love, to love the way God does, to love our neighbors and even ourselves selflessly and unconditionally, without desiring a reward, without wanting something in return.

Unconditional Love

If we carefully observe the social life around us, we see the meanspirited, the ambitious, and the selfish, but we also see numerous physicians, nurses, teachers, and caregivers making the miraculous leap from erōs to agápē.

To love well, we must be loved unconditionally first. Psychologist René Spitz discovered through the study of hospitalized children that a child’s very first bond with another person is the basis for the later development of human love and friendship.[13] A child under two years of age, if deprived of a single person’s continuous care for three months or more, develops emotional trauma that may result in death, even though the child is provided with perfectly adequate food, shelter, hygiene, and medication by a succession of compassionate nurses. In such circumstances, no one is exclusively responsible for loving the child, so she cannot form an attachment to another person.

Spitz also discovered that when a child experiences a mother or a primary caregiver as a source of both intense pain and comfort, all the child’s emotions are blurred, and its capacity for friendship is severely diminished. A child severely deficient in love is not interested in his toys and is prone to violence in later life. An empty, uninterested facial expression is a characteristic of a child lacking love. Many a child’s life has been saved from ruin by the sustained, unconditional love of a grandmother, an aunt, or a nanny. If a mother or continuous caregiver showers the baby with gratuitous love, the infant feels, “I am wonderful, just because I am.” The child learns to love itself the way the mother or caregiver loves him. The young child then extends this self-love to a love of the world. The child feels, “It’s good to be alive; it’s good to be surrounded by such good things.” With unconditional love, a child learns to trust life.

A child nurtured and protected by love can as an adult suffer the most outrageous misfortunes and still believe she and the world are fundamentally good. If success is measured by human relations and friendship, not wealth and career achievement, then the kind of love a child receives is a better predictor of her course in life than environment, IQ tests, or genes.

3. We Are Rational Beings

We humans are born radically incomplete; we are unfinished by nature, which means that we are not enslaved to anatomy like animals are. The natural tools, weapons, and armor of animals serve only one specific task and cannot be put aside or changed for others, severely restricting the lives of animals to limited activities. A mole’s short, chunky paw is an outstanding digging tool but cannot hold anything. An eagle’s talons are perfect for clutching small animals but are useless for digging. The human hand can perform all the tasks achieved by the specialized tools of animals: it can dig with a hand shovel, stab with a sword, cut down a tree with a saw, and perform thousands of other activities without being restricted to any single one of them.

Unlike the instincts and organs of the other animals suitable only for specific tasks that lock them into one way of life, the human mind and hands are general tools. The human hand is tailored to the human mind. Planting a garden, making a canoe, and painting a picture are rational activities; in each case, the hands move under the direction of the mind to achieve the desired end. Thus, human activity is rational.

We Desire to Know by Nature

As soon as a child learns to speak, an unending barrage of questions begins as every parent knows. Children are experts at wondering, for they see the world with new eyes. Some of us preserve the spontaneous wonder we had as children. The actual life we live first as children and then as young adults—if we did not have our questioning turned off by parents and teachers and if we did not become corrupted by the desire for power, wealth, and material comfort—shows that one purpose of human existence is to reveal, or to uncover, or to encounter more and more truth. Just as the sunflower cannot help but turn from the dark toward the light, the human being cannot help but shun falsehood and seek the truth.

The Senses Need Training

Knowing begins with the senses; unlike animal perception, human senses require training. The untutored tongue cannot distinguish a St. Emillion from a St. Julien, though a wine enthusiast not only can recognize the region the wine came from but the chateau and the vintage year. We can train our hearing by learning a musical instrument and our eyesight through drawing lessons.

Chief Standing Bear reports that Lakota children “were taught to use their organs of smell, to look when apparently there was nothing to see, and to listen intently when all seemingly was quiet. A child who cannot sit still is a half-developed child.”[14]

The Good Mind

Formal education generally treats students as passive spectators, contrary to Einstein’s understanding: “The value of a college education is not the learning of many facts but the training of the mind to think.”[15]

The study of music, language, literature, mathematics, and science develops our capacity to define, analyze, and draw conclusions. For these studies to bear fruit, we must acquire more than knowledge, techniques, and general rules. We must be trained to think well; this is possible because we are unfinished by nature and thus must perfect ourselves. A good mind is open, thinks concretely, and seeks interconnections.

Openness

The open mind willingly accepts truth from any source. Mozart, a model of open-mindedness in music, said, “People make a mistake who think that my art has come so easily to me. Nobody has devoted so much time and thought to composition as I. There is not a famous master whose music I have not studied over and over.”[16]

If we admit our ignorance to ourselves, we will see that our opinions carry little weight and thus need to be examined, especially culturally-given opinions that most of us take as obviously true. If we are constantly aware of our ignorance, then we will always have the freshness and innocence of a beginner who is astonished again and again by the new wonders he or she encounters. We will never forget that all learning begins with wonder and amazement and that profound truth appears strange to cultural opinion.

Concreteness

In thinking, concreteness yields clarity. One of the maladies of modern life is substituting a fuzzy verbal world for actual concrete experience.

Physicist Enrico Fermi was known for his quick and clear thinking. One reason for his mental agility and clarity of thought was he had “a whole arsenal of mental pictures, illustrations, as it were of important laws or effects.”[17] He would not simply keep Newton’s third law in his head, for example. (To every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.) He would discover and etch in his memory a paradigmatic example of the law, such as a man jumping from a boat to a dock where clearly the boat must move away from the dock with a momentum equal to the man moving toward it.

Interconnections

Without seeking interconnections as we learn, what fragile knowledge we gain can be easily lost. We, thus, should form the habit of connecting what we are learning to what we already know. For example, when we hear Stephen Daedalus, the protagonist of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, argue that the three universal qualities of beauty in the arts are wholeness, harmony, and radiance, his translation of Aquinas’ integritas, consonantia, and claritas, we should seek to see if this trio describes beauty in the sciences. Einstein does give these three elements: “A theory is the more impressive the greater the simplicity of its premises is, the more different kinds of things it relates, and the more extended its area of applicability,”[18] in agreement with Joyce and Aquinas.

The Joy of Knowing

Every naturalist enjoys the pleasure of exercising their powers of observation. Charles Darwin describes his first day in a tropical jungle: “The day has passed delightfully. Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who for the first time has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again.”[19]

The beauty of nature connects a Lakota Indian Chief, a great English naturalist, and a pupil in a one-room schoolhouse on the American prairie. Fully developed senses allow us to receive the gifts of nature: beauty, wonder, mystery, and places to meditate—the means to discover that we belong in this world as much as the wild sunflowers and the soaring hawks.

4. The Spiritual Nature of Homo Sapiens

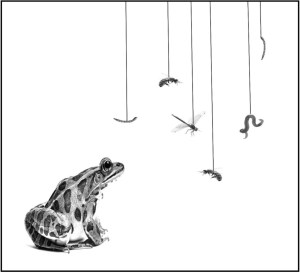

Non-moving insects and worms do not exist for a frog. It will starve to death although surrounded by food.

Surprisingly, the study of the perceptual life of frogs revealed the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens. In a classic study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lettvin, Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts inserted tiny electrodes into a living frog’s optic nerve to measure the electrical impulses traveling to the frog’s brain. Using this technique, the researchers formed a good picture of what the frog sees. They found that when a small object is brought into the frog’s field of vision and left immobile, the frog’s eye sends electrical impulses to the brain for a minute or so, but then ceases to do so. After a short time, then, the object is no longer there as far as the frog is concerned.

The reason for this disappearance is that the frog’s retina is designed to detect small moving objects. If a small object ceases to move in the frog’s field of vision, its retina cancels it out of the frog’s world. Furthermore, the retina’s circuitry computes the velocity and trajectory of a small moving object so that the frog can aim its tongue ahead of where the object actually is.

The researchers reported that “the frog does not seem to see or, at any rate, is not concerned with the detail of stationary parts of the world around him. He will starve to death surrounded by food if it is not moving. His choice of food is determined only by size and movement. He will leap to capture any object the size of an insect or worm, providing it moves like one. He can be fooled easily not only by a bit of dangled meat but by any small object.”[20] A frog cannot see a fly as such; it sees small moving objects. (See illustration.[21])

The MIT researchers also discovered nerve fibers that respond to the net dimming of light. These specialized fibers alert the frog to the danger of a nearby large moving object. The frog’s eye has only two categories: “my predator” and “my prey.”

Similarly, ethologist Jacob von Uexküll, among the first to document the remarkable specificity of animal perception, discovered that a jackdaw is unable to see a grasshopper that is not moving: “A jackdaw simply does not know the shape of a motionless grasshopper and is so constituted that it can only apprehend the moving form. That would explain why so many insects feign death. If their motionless form simply does not exist in the field of vision of their enemies, then by shamming death, they drop out of that world with absolute certainty and cannot be found even though searched for.”[22]

The narrowness of animal perception can produce astonishing results. Here is one of the hundreds of instances discovered by ethologists. A deaf turkey hen will peck all her chicks to death as soon as they are hatched. The distressed cheeping of the chicks is the only stimulus that inhibits the hen’s natural aggression in defense of her nest. The cheeping alone evokes a maternal reaction in the hen. Without the cheeping, a chick is judged by instinct to be an enemy and is attacked. A hen with normal hearing will attack a realistic stuffed chick if it emits no sound and is pulled toward the nest by a string. Conversely, she will respond maternally to a stuffed weasel (the turkey’s natural enemy) if it has a built-in speaker that produces the cheeping of a turkey chick.[23] Just as the frog cannot see a fly, the mother turkey cannot see its offspring!

The great discovery of ethology is that animals do not perceive what things really are; an animal’s perception is limited to a few key elements that will cause it to act. Uexküll summarizes the scientific study of animal perception with a powerful metaphor: An animal’s world is not the world we see but more closely resembles “a small, poorly furnished room.”[24]

Of all the natural natures, only human beings can grasp a whole. The study of animal perception re-discovered the spiritual nature of Homo sapiens—the capacity to be connected to all that is, a fundamental principle of every wisdom tradition.

Ancient Greek: “The human soul is, fundamentally, everything that is.”[25]

Hindu: “Thou are that.”[26]

Christian: “Every other being takes only a limited part of being whereas the spiritual soul is capable of grasping the whole of being.”[27]

Jewish: “At opposite poles, both man and God encompass within their being the entire cosmos. What exists seminally in God unfolds and develops in man.”[28]

Islamic: “Who knows his soul knows his Lord.”[29]

Chinese: “He who cultivates the Tao is one with the Tao.”[30]

Native American: “To walk the path of beauty, you must connect to all things, take them seriously, with reverence.”[31]

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Endnotes

[1] See Harlan Lane, The Wild Boy of Aveyron (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) and François Truffaut, director, Wild Child, Les Artistes Associés, film.

[2] Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (Mineola, New York: Dover, 1996 [1903]).

[3] Helen Keller, The World I Live In (New York: The Century Co., 1904,1908).

[4] Ibid.

[5] For a witty, short history of the efforts to teach American Sign Language to nonhuman primates, view the last twenty-five minutes of Robert Sapolsky, Human Behavioral Biology, Lecture 23 On Language.

[6] Robert Fantz, “The Origin of Form Perception,” Scientific American 204 (May 1961):69.

[7] Daniel G. Freedman, Human Infancy: An Evolutionary Perspective (Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum, 1974), p. 30.

[8] The four loves are loves of the soul and do not exhaust the realm of human love. For example, the love of money or pizza is called concupiscence, defined by the craving for the pleasant that includes both the soul and the body. See Aquinas, Summa Theologica, The First Part of the Second Part, Question 30.

[9] Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (New York: Harper, 2006 [1956]), p. 4.

[10] For a detailed discussion of the three kinds of friendship, see Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics, Bks. VIII and IX.

[11] See Aristotle, Rhetoric, Bk. II, Ch. 4, line 1381a.

[12] In The Bhagavad Gita, the Sanskrit word that corresponds most closely to agápē is tyāga, the selfless action that has no desire for personal reward. See The Bhagavad Gita, trans. Eknath Easwaran with chapter introductions by Diana Morrison (Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press, 1985), pp. 202-204 and 18.11.

[13] René Spitz, The First Year of Life: A Psychoanalytic Study of Normal and Deviant Development of Object Relations (New York: International Universities Press, 1965). See also Robertson, J., and J. Bowlby. “Responses of Young Children to Separation from Their Mothers.”Paris: Courr. Cent. Int. Enf, 1952.

[14] Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), pp. 69-70.

[15] Albert Einstein in response to not knowing the speed of sound as included in the Edison Test: New York Times (18 May 1921).

[16] Mozart, quoted by Joseph Machlis, The Enjoyment of Music (New York: Norton, 1963), p. 308.

[17] See S. M. Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (New York: Scribner’s, 1976), p. 163.

[18] Albert Einstein, “Autobiographical Notes,” in Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, ed. Paul Schilpp (New York: Harper & Row, 1959), p. 33.

[19] Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle (New York: Dutton, 1967), p. 8.

[20] J. Y. Lettvin, H. R. Maturana, W. S. McCulloch, and W. H. Pitts, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers 47 (November 1959): 1940.

[21] The image is a composite of Shutterstock images: Michiel de Wit, “Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens);” Africa Studio, “Fishhook with worm isolated on white background;” Irink, “Bee isolated on white;” Anneka, “Mealworm or worm on a fishing hook as bait;” and Vnlit, “Dragonfly macro isolated on white background.”

[22] Jacob von Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, trans. Alexander Dru (New York: Mentor, 1963), p. 86.

[23] Konrad Lorenz, On Aggression (New York: Harcourt & World, 1963), pp. 117-118.

[24] Uexküll, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 85.

[25] Aristotle, De Anima, Bk. III, Ch. 8, 431b.

[26] Chandogya Upanishad, 6.12-14.

[27] Thomas Aquinas, quoted by Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis Culture, p. 88.

[28] Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), p. 152.

[29] Jalaluddin Rumi, Signs of the Unseen: The Discourses of Jalaluddin Rumi, trans. W. M. Thackston, Jr. (Putney, Vermont: Threshold Books, 1994), p. 59.

[30] Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching, No. 16.

[31] Billy Yellow, interview by David Maybury-Lewis, Millennium, aired on PBS, 1992.

The featured image is the Wild Boy of Aveyron and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News