We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

There is something immoderate about Sibelius’ Violin Concerto—something vulnerable and unspeakably beautiful, right there along something dark and brooding. The piece illustrates that not only do darkness and beauty coexist, they enhance each other.

It’s complex, gripping, devilishly complicated, and sounds like no other concerto in the violin repertoire. Listening to Finnish composer Jean Sibelius’ violin concerto, you hear dark, wintry night; pure, crystalline melody above a cushion of pianissimo strings (starlight has a sound!); brooding motifs; a violin that laments but never stops singing. In the second movement, the adagio di molto, a gorgeous melody arises amid the lower voices that makes your heart swell and swell, even as it’s breaking.

“The movement is so haunting, so intense,” my violinist character Montserrat recounts to Alice, the narrator, in my novel, Off Balance. Years back, she’d performed the concerto in an international competition, under a crushing weight of anxiety and despair.

“You hear the brass from the orchestra slowly building, and there you are with your violin, desperately trying to… I don’t know. Stay alive. Survive against the odds. The pain of it—I felt like a bird in the dead of winter, knowing I would die, because the cold was just too much to overcome. But you know what? I’ll bet that bird keeps singing sweetly until the instant before it dies. Because what else can you do if you were born to sing? That’s what the Adagio will always be for me. That feeling.”

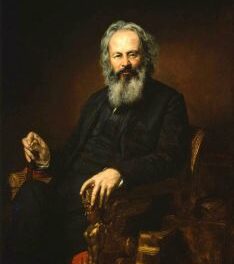

More on my beloved violinist character later. First, let’s talk about Sibelius. Most people talk about his seven symphonies as being at the core of his success as a composer. Some of them I quite like (No. 3 in C-Major and the No. 5, with its glorious ending). But the Violin Concerto rises above them all, timeless and omnipotent, more spiritual experience than entertainment. Commenced in 1899, completed in 1904, a mediocre premiere prompted Sibelius to hold off on publication. He revised, whittled it down, and the concerto re-premiered in 1905, this time to acclaim. And oh, what acclaim it deserves.

Jean Sibelius is not just Finland’s most famous composer; he’s a cultural colossus, a national hero, having played a symbolic role in Finland’s quest for independence (granted in 1917). He’s a household name throughout the world, certainly the classical music world. His music is rich and unforgettable, and the classical music legacy he left behind for Finland is unparalleled in any other country in the world. (The annual Finnish expenditure on the arts is roughly two hundred times per capita what the United States government spends through the National Endowment for the Arts. Further, Finland’s musical culture has produced more world-class composers and performers per capita than any other country.)

For being a hero and musical icon, however, the guy was human, and he struggled. For the last thirty years of his life he didn’t publish new material, although he worked away at an eighth symphony for much of that time. Like so many creative artists, he struggled particularly on the inside. In 1927, when he was sixty-one, he wrote in his diary, “Isolation and loneliness are driving me to despair. . . . In order to survive, I have to have alcohol. . . . Am abused, alone, and all my real friends are dead. My prestige here at present is rock-bottom. Impossible to work. If only there were a way out.”*

For many an artist, creativity tends to arise amid an environment of immoderation. That’s why you hear about alcoholism, suicide, rehab, breakdowns, among the artistic sect of the population. I’ll admit it; I myself feel manic, rather psychotic, when I’m in the process of producing my most creative work. It’s the place where you’re on fire inside. I can feel that, like a tactile presence, in good art. I can tell when an artist has gone inside the fire, trudged through the long, dark night of the soul, gotten lost in those places.

There is something immoderate about this concerto that enormously appeals to me. Something vulnerable and unspeakably beautiful, right there along something dark and brooding. They illustrate that not only do darkness and beauty coexist, they enhance each other. How fitting that a Finnish composer should have so aptly illustrated the beauty of light amid so much wintery darkness.

Listen to the Sibelius Violin Concerto for yourself and tell me what you think. Joshua Bell does a knockout job with the Oslo Filharmoniske Orkester, the young, winsome Vasily Petrenko conducting.

Ten years ago, in researching my second novel, I decided to give my character, Montserrat, the Sibelius Violin Concerto for her final piece in a competition she was desperate to win. (A long, rather dark backstory I won’t elaborate on here.) She and I both lived within the Sibelius all that fall. And the next fall, when I revised the manuscript. And the next fall, when I re-revised. And when that novel didn’t sell, I picked her and the Sibelius up and inserted them in the next novel-in-progress. She’s there, now, in Off Balance. Her life is safer now, with its happily ever after, prize won, career launched, loving spouse found. It was fun to move her; I love being able to create happy endings for my characters. But at one point, my narrator Alice goads her into sharing the darker side of her successful career as a violinist. Bad girl, Alice. Your insecurity is showing.

I’ll never publish that earlier novel; it’s too dark. The characters suffered too much. But I do love the scene where Montserrat performed the Sibelius. After the months I’d spent crafting and re-crafting, it now feels so weirdly personal, as if the performance had happened to me. That’s what happens to a novelist who gets too deep into their work. Or maybe that’s what happens when you listen to the Sibelius. It has that much power over you.

So, allow me, dear reader, to share a bit more of Montserrat’s story.

Desperate Little Secrets

The next morning— in truth, only a few hours later, Montserrat woke, and worked her way out of the unfamiliar bed, grimacing at the horrible sickly-sweet taste of alcohol in her mouth. In the gleaming marble and chrome bathroom, she looked at the stranger in the mirror and squeezed her eyes shut till the urge to throw up had passed. Then she ran the hot water till it reached scalding, scrubbed her face, her hands, until they both felt raw and tingling. She dried off, dressed and slipped out of the apartment. Outside, she walked for a mile in the drizzly, grey London morning before catching a bus to her flat. The music, she told herself. The Sibelius. The only thing that mattered. Although she’d planned to stay away from the concerto that day, competition day, it was the only place she could bear to be for the next ten hours. That, and the Bach Chaconne, the purest, most out-of-reach piece of music she’d ever played—the musical equivalent of prayer. Or confession time.

Sleep and appetite eluded her as she slowly, methodically, worked her way through a series of scales and arpeggios, then tricky passages of the concerto, then the Chaconne. Back to the Sibelius and again to the Chaconne. She grew calmer, settling into that meditative state of heightened sensitivity from where she could best perform. And then it was time.

She was the second of the six finalists to play to a sold-out crowd at the Royal Festival Hall, kept waiting an extra minute while she retched into a off-stage toilet. She stumbled onstage finally, the bright lights assaulting her, the rustle of her taffeta evening gown whispering as she walked unsteadily to her spot beside the conductor. She tuned the Vuillaume, tightened her bow an extra millimeter, then nodded to the conductor.

The opening bars were always the worst. She’d never outgrown her stage fright, even after years of increasingly high-pressure performing. She knew the stamina required for the Sibelius, even under the best of circumstances, was enormous. But her months of preparation paid off, the way she’d learned, unlearned, relearned from a different mindset, played passages backwards, even playing in the dark confines of a closet. Rote learning, and technical analysis now slipped away as her fingers landed with perfect memory and accuracy on every note. The music seeped into her, replacing her stage fright with focus.

The first movement was theatrical and epic, her violin’s solo voice flitting amid ever-building intensity from the orchestra alongside her. The passage work was fiendish—double stops with sustained trills; rapid slides from the lowest notes up to the highest, octave double-stops, all of which had to impart that ineffable sense of longing Sibelius conjured so well, a winter of the soul, haunting in its beauty, crystalline in its clarity.

The first time she heard the second movement, the adagio di molto, she’d bowed her head and wept. While she’d learned to curtail the emotion, the feeling was still there in the violin’s lament, dissonance from the brass section keeping the movement from ever turning maudlin. It was the aural representation of hope amid darkness. This then, was what she struggled with, time again time again, much like with the Bach Chaconne, this attempt to connect with something so divine, so out of reach. She could only play the music and hope her despair didn’t mar the effect. Tonight, especially, the despair.

Never before had she relied so heavily on the orchestra, nor been so rewarded by their efforts. As if sensing her failing energy, they hovered close in the adagio, then supported her in the spirited, syncopated third movement as she pulled from unknown reserves to tackle the music. For an instant, she stepped outside herself, marveling at the cleanliness of the tricky passage work, the electric mood generated throughout the hall. She observed the pale, swaying soloist and idly wondering how much longer she could last before her energy failed her.

The answer: after she’d finished. Amid the thunderous applause, she shook the conductor’s and concertmaster’s hands, managed a bow to the audience without tipping over. She made her way to the wings, which were now growing curiously fuzzy and indistinct. There, she felt arms grab at her and catch her Vuillaume as she slid to the soothing coolness of the concrete floor.

Dark, peaceful coolness.

Republished with gracious permission from The Classical Girl (October 2015).

This essay was first published here in January 2018.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

*Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News