We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

As war continues in Israel and Gaza accompanied by anti-Israel protests on college campuses, the “settler colonialism” smear against Israel is amped up by the hard Left, the academic industry, and, especially, by “organizers” eager to destroy the social and economic strides made between Arab states and Israel in the Abraham Accords and before.

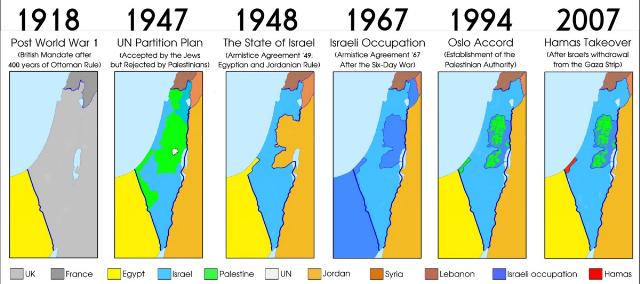

Palestinian Arabs might never have had a prayer of having their own state had the Jewish State not been created. They were totally under the thumbs of Jordan and Egypt, who attacked Israel in 1948 claiming to defend Palestinian Arabs but really seeking to block both a Palestinian Arab and a Palestinian Jewish state under U.N. partition. Still, the Palestinian Arabs refused a state even after they and Jordan and Egypt lost the war.

Ironically, Palestinian Arab chances at independence returned when Israel won Gaza and the West Bank, Sinai, the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem, in a defensive 1967 war with Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Israel immediately sought to trade “land-for-peace.” It was settler colonialism theories, often forged on anti-Israel hatred (as found, for example, in the 1964 charter of the Palestinian Liberation Organization) that discouraged Arab nations and Palestinian Arabs from negotiating for peace. In recent years, through the Abraham Accords and Arab nations outgrew these theories, preferring security against Iran and the prospect of peace and of economic cooperation. But the Palestinian Arabs — and world academia — continue to shout “settler colonialism.”

The extent of academic obsession with “settler colonialism” is painfully apparent in an article published in May by the Columbia Law Review that has less to do with legal theory than with Israel-bashing. The article pushes for “codified legal frameworks” against “ethnic cleansing” and “settler colonialism” by declaring Israel’s existence as a Jewish State and Israel’s subsequent laws and actions to be one giant “Nakba” or “set of catastrophic transformations imposed by force on Palestine, the Palestinian people, and, indeed, the Arab world more broadly.” Here, the meaning of “Nakba” (catastrophe) is ballooned to refer to Everything Israel. The writer does not even tell us if “Nakba” has any status or mention in the laws of Arab nations or of Sharia law.

The article is nothing more or less than a bibliographical checklist of any and all grievances against the State of Israel, whether by historians, human rights activists, or Palestinian Arab rejectionists of the Jewish State. Most of the cited sources are partisan, ideological, and polemical. Few deal with issues of legal theory and offer actual critiques of law, whether Israeli or international. Political or social or even safety causes of Israeli laws condemned here (but never truly analyzed) are simply not discussed. The article is one continuous indictment of Israel, proclaiming that “Palestine remains the most vivid manifestation of the colonial ordering that the international community purports to have transcended.”

Even fundamental international documents are hardly mentioned, like U.N. Resolution 242, which called for Israel’s withdrawal from territories (but not all territories) won in the 1967 war as an “application” of “the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East.” There is no discussion of how this resolution can be interpreted forty-two years after Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula (resulting in peace with Egypt) and almost twenty years after Israel dismantled twenty-one settlements (populated by 9000 of its citizens) in Gaza, including ancient, continuous Jewish communities. Israel left in Gaza hundreds of greenhouses, some specially built, out of heartfelt wishes that the fully Arab population would prosper in agricultural and horticultural exports, only to be constantly targeted by (pre-Hamas rule) Gazan missiles days after the withdrawal.

It is astounding that an article in a legal journal would declare as its objective “not to examine the legality of the Nakba as much as to generate a legal framework from the Palestinian experience of the ongoing Nakba” — in other words, to advocate for the creation of laws instead of scrutinizing existing laws. The author offers no comparative investigation of laws regarding Jews in Europe or in Arab countries. Nor does he explore the origins or the development or the causes, internal or external, for Israel’s defining “law of return” (welcoming all Jewish immigrants) and the state’s more recent call for a “Nation State Law.”

The author patronizes Israel by preaching that the Jewish State should not base its legal education on the “ideological underpinning that barely challenges the Zionist tenet of a Jewish democratic state.” But this is a lazy reproach in that he does not analyze and compare particular laws that he regards as attempting to define, or serving to undermine, Israeli democracy. The most “objective” question he poses is, “Does the crime of apartheid lie in a particular subset of Israeli policies or is it the raison d’etre of the Israeli regime?” He never raises the question of whether countries rooted in Arab ethnicity and/or in Islamic law are to be considered ipso facto “apartheid.”

Still, the author insists that he is dealing with legal concepts or theory in order “to overcome tensions and contradictions.” Is that the province of a law journal?

The sorry state of academic theories, and their inability to bring understanding and healing to world conflicts, is fully and painfully illustrated in the Columbia Law Review’s dedication of so many pages to this catalogue of Palestinian grievances, in which all the writings to date condemning “settler colonialism” are distended to attribute to Israel every imaginable social and political evil.

The author concedes that there “is a long and rich history of Jewish existence in Palestine that is not premised on systemic violence, domination and ethnonational superiority.” He concludes by decrying that the “UN Partition Plan granted fifty-six percent of Palestine’s territory to the ‘Hebrew State’ at a time when Jewish owned lands did not exceed seven percent.” But of course, if one figures in lands bought by the Jewish National Fund from the Ottoman empire (in which many Arabs were tenant farmers) and from absentee Arab landowners, and considers that much of the land given postwar to the Jewish community had been deemed useless swamp, not to mention the seizing of Jewish Jerusalem by Jordan, the argument for Jewish ownership is stronger.

But is refutation of “settler colonialism” theories even a matter of proving “ownership”? At the heart of the post-World War II establishment of the State of Israel by the Allied and other countries in the United Nations was a major, legitimate issue which the editors of the Columbia Law Review, for whatever reason, did not ask their contributor to consider.

We still hear from Palestinian Arabs that they should not have to suffer because Europe tried to exterminate its Jews. The truth is that Palestinian Arab leaders and rank-and-file Palestinians who had lived under British rule, led by their mufti, supported the Nazis and even advised them on how best to wipe out Jews in Europe and in the Middle East. So did many Arab nations like Egypt and Syria who did not want a new nation, Jewish or Arab, in Palestine.

In 1948, Britain relinquished its colonial stronghold in Palestine, due in no small measure to the resistance of the determined Jewish community. A Jewish State was forged after the Allied Victory over the Nazis for the people most devastated by the Nazis, with the fullest possible international support at the time, with the expectation that the more than twenty Arab states would absorb any refugees and the expectation that Israel would absorb all Jews from Europe and the Middle East and around the world, most of whom had no other place to go. Zionist leaders accepted the British reduction of territory for the Jewish State, a concession to Arab nations, even though much of Israel’s land was desert or swamp.

The very term, “Nakba,” is taken totally out of context, at least in its original use, in settler colonial theory broadsides like the one cited above. As Sammy Stein of the Glasgow Friends of Israel eloquently reminds us, the first significant tract that uses that term was penned by Constantin Zurayk, a Syrian Arab Christian, who characterized the Nakba-disaster as the failure of the Arab nations to stop the establishment of the State of Israel.

Zurayk took Palestinians to task for having “fled and evacuated their cities and strongholds, and surrendered them to the enemy on a silver platter.”

Ironically, the author of the Columbia Law Review screed concedes in a footnote that “The question of whether Palestinians fled their homes because of fear or were actively expelled by Zionist forces is one of little importance” — a question hotly debated among historians.

The ultimate question is whether settler colonialism theory can contribute to peace and security in the Middle East, and the answer is “No.” Even leftist Iranian dissident Arash Azizi complained back in 2021: “Many on the Left seem to believe that using the moniker ‘settler-colonialism’ …somehow magically leads to a solution. As a result, instead of specific political demands, we have calls that are, at best, vague.”

This courageous comment comes from an advocate of a binational state in Palestine who accepts many of the tenets of settler colonialism theory and opposes BDS boycott demands only insofar as they cut ties with the Israeli Left, with whom he hopes to “build this one-state.” Though he maintains that the world must “stand by Israeli citizens killed by Hamas’s rockets,” his idealistic “one-state” vision, once proposed by some early Zionist leaders, would only encourage those whose obsession with dismantling Israel by any means has led to their advocacy of settler colonialism theory and hope to see it applied in any way necessary.

The postwar context of the founding of the State of Israel already placed the Jewish State beyond settler colonial theory and interpretations of Nakba, whether legal, social, or political. The true nakba for the entire Middle East was Arab support of Nazism and the cutting of ties with democratic and free nations. The best hope for the Middle East is to uphold the efforts of those Arab nations which led the way toward cooperation with Israel and the United States through initiatives like the Abraham Accords, which already included demands for the improvement of the Palestinian situation, and which Hamas sought to undermine last October 7.

Image: איתמראשפר

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News