We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Cristina Neagu specializes in the literature and arts of the Renaissance. She has a doctorate from the University of Oxford. The fields in which most of her work has been conducted include Neo-Latin literature, rhetoric, art history and history of the book. From 2003 until 2023 she was Keeper of Special Collections at Christ Church, one of the most prestigious Colleges of the University of Oxford, where, among other things, she was in charge of the Digitisation Project. The first to be initiated by a College, the aim of the project was to produce high-resolution digital copies of every manuscript and unique or very rare item in Christ Church Library’s exceptional collections, and to facilitate a viewing environment for these images on the Digital Bodleian platform. For 20 years, she was also Editor of several monographs and the journal issued by Christ Church Library. Her own publications include studies on humanism during 15th-century in Central Europe, text and image in early modern art, various articles and a monograph, Servant of the Renaissance, on the work of Nicolaus Olahus, one of the lesser-known humanists and friends of Erasmus. Currently she works as a Researcher associated with the EMLO (Early Modern Letters Online – EMLO) Project at the University of Oxford. This is part of the “Cultures of Knowledge: Networking the Republic of Letters,” a collaborative and interdisciplinary research project based at the Faculty of History, using digital methods to reassemble and interpret the correspondence networks of the early modern period. EMLO brings together experts in history, philosophy, science, art, languages and literature with information specialists and systems developers, transforming engagement with early modern letters. At present Cristina Neagu is involved in working on the extensive correspondence of Albrecht Dürer and his circle. She is also engaged in writing a book based on the discovery of an unknown manuscript linked to a specific copy of Dürer’s Kleine Passion.

Robert Lazu Kmita: Dear Dr. Cristina Neagu, there have been more than twenty years since you started extensive research, in the generous field of “Renaissance Studies.” The genesis of both your academic and personal relationship with Oxford University traces back to the pursuit of your doctoral studies focused on Nicolaus Olahus (1493–1568). Why Olahus? How did you discover this Renaissance Catholic scholar, and what specifically sparked your interest in his works— an interest that has not waned even today?

Cristina Neagu: It is hard to believe it has been so long. Now that you mention it, I realize it is thirty years precisely. And it has been an adventure—a remarkable, humbling, fully enriching adventure. It all started in 1993 with my arrival at the University of Oxford with a Soros Scholarship, and continued, from 1994, with embarking on the doctorate you refer to. Nicolaus Olahus was an unexpected gift that Oxford presented me with. Of course, on a superficial level, I was aware of Olahus’s contribution before having the chance to plunge into the earliest editions of his works. The manuscripts came later. Most of them are—as one would expect—in Hungary. But the encounter with the early editions, this happened in the inspiring peace of the Bodleian Library. I was immersed in a different project to start with. It involved exploring the literature produced in Central Eastern Europe during the 16th century. One day, while looking for samples of non-religious poetry, I remembered Olahus and requested his works, starting with the Carmina. Meeting the texts was an eye-opening experience in so many ways. This is a relatively large corpus of poems (some 1400 lines) which, I quickly realized, had not, at that time, been the subject of any significant study. Only short chapters or paragraphs in larger biographic works occasionally focused on his verse. I also realized that this neglect did not reflect the quality of the poetry. On the contrary, the richness of Olahus’s poetic output and its artistic and historical connotations, made me think of this volume as a subject worthy of interest.

It took a while until the Olahus project found its sea legs. This is entirely unsurprising, for, although Olahus’s life as a diplomat, man of the church and humanist at the court of both Queen Mary of Hungary in Brussels and King Ferdinand I at Buda, had been explored to a certain degree, and some of his works were occasionally examined, most of his writings lingered completely ignored. This was unchartered territory. It should have felt at least a little daunting. But it didn’t. I had absolute confidence I could pull it off. Thinking of this now, I understand that one of the reasons why this happened was that, from the very beginning, I was granted the freedom to follow my own line of approach, but not left to feel alone. Every step of the way, my thoughts and what I discovered were put to the test in frequent discussions with extraordinary people, many of them authors of seminal books that I read with undiluted wonder, specialists in the field, but not necessarily close to Olahus and his circle. They were, however, genuinely interested. I owe these people a lot, although I have no doubt, they would think I exaggerate. I don’t. In the rarefied and intensely competitive world of academia, their gentle (sometimes fleeting) guidance, helped me never lose faith in being able to take the project to a worthy conclusion.

Here my first thanks is due to Professor Terence Cave, of the University of Oxford, my devoted supervisor. Without his scholarly advice and criticism, I would have been treading on a very different path. For their unflinching support, comments and suggestions, I am similarly indebted to Professor Douglas Gray and Professor D.A. Russell, also of the University of Oxford, to Professor J.B. Trapp and Dr Jacqueline Glomski, of the Warburg Institute in London, to Monsignor Leonard E. Boyle, Prefetto of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, to Professor Hugo Tucker, of the University of Reading, and Professor Jozef Ijsewijn, of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. I have also been privileged to try out my arguments in long and thorough discussions with my husband, Tom Costello, Professor of Early Modern English literature. He read my manuscript in every successive draft and supplied me with indispensable help. Some of these exceptional people are no longer with us, but the dialogue they initiated thirty years ago has stayed with me. This is, in fact, one of the most precious lessons that Oxford has conveyed. That we grow in, and by means of, dialogue, taking turns to speak and to listen, cultivating our own voice, while exploring fresh perspectives, and paying attention. Always paying attention.

Clearly, my first tentative steps in Oxford were sheer joy. I was working in what I perceived to be the best place possible (certainly, the intellectual communion it offered was second to none), and I had stumbled on an inspiring subject, in real need of in-depth study. Things couldn’t be better. I had so much to do. Olahus’s poems were effectively untouched. Of his voluminous correspondence with some of the most celebrated figures of his time (Erasmus included), only a small part was known and edited. Similarly, Olahus’s devotional writings had never been critically examined. At first sight, these might appear to be rather dull and over-didactic, but as they cover many themes dealt with only at the concluding meeting of the Council of Trent, they highlight and comment on important contributions by individual theologians seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within. Even the treatment of Olahus’s best-known works, the Hungaria and Athila, invited re-assessment. No scholar had ever discussed them other than separately: the Hungaria as a geographical survey, and the Athila as an independent historical piece. However, when regarded together in the light of Renaissance dependency upon genre-systems, these two titles emerge as a single chorography in two books. Furthermore, and perhaps most intriguingly, there is this short but exquisitely written piece, the Processus sub Forma Missae, a vision of the alchemical process regarded from the perspective of Christian liturgy. Written under the pseudonym Nicolaus Melchior, the work raises the difficult question of authorship and Olahus is among the candidates under consideration, as parallels between the life and work of Melchior and Olahus can be established.

You are right. Although, over the years, research has led me towards many other topics, my interest in this captivating Renaissance Catholic scholar has not waned. After the doctorate my work materialized in a book, Servant of the Renaissance: The Poetry and Prose of Nicolaus Olahus. What this book offers as new in the context of Olahian scholarship is a discussion of the sort of writer Olahus regarded himself to be, and how he perceived his role as contributor to the intellectual milieu which formed him. This approach reveals the meticulously built, non-accidental character of his biography and the programmatic nature of his writings.

Far from being a private pastime and mere luxuries of a mind in need of rest from the turmoil of his worldly duties, the texts Olahus composed are very special. He wrote as a rhetorician, not just in the sense that he composed in an elegant style, but also to persuade, delight, move and impel to action. His writings thus enter a symbiotic relationship with society, acting as a channel of creative energy for the humanist as a ‘vir civilis’ engaged in the exercise of duty. If one analyses his writings as a whole, there are features which appear to grant them a significant degree of coherence and unity. In fact, there is little prospect of understanding the full value of Olahus’s literary work (beyond its much discussed and often overstated documentary nature) unless one returns to his texts with a fresh eye, bearing in mind their author’s rhetorical imperatives. All this makes Olahian studies exceptionally gratifying and forever surprising.

In terms of recent work on the subject, further research related to the alchemical piece, work that I conducted in the past few years, called forth the need of an update. This appeared not long ago as a chapter in the volume Nicolaus Olahus 450, edited by Emöke Rita Szilágyi. As to what may be in the pipeline, here too there is rather exciting news. 2024 has started with the decision to include Olahus in the Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO) catalogue. EMLO is a complex platform, part of a larger project hosted by the History Faculty at Oxford, designed as a combined finding aid and editorial interface for detailed descriptions of early modern British and European correspondence. I am currently working to describe and integrate the correspondence of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and his circle as part of EMLO, but will also return to Olahus’s enormously stimulating large collection of letters.

Robert Lazu Kmita: After dwelling for such a long time in the “vicinity” of Olahus’s writings, how would you respond to the question regarding their essential characteristics: are they meant to endure primarily through the ideas conveyed or through their aesthetic value? And, more specifically, how do you appreciate the value of his poems in the broader context of Early Modern verse? Can you conceive of Olahus’s Carmina as being included in a “mainstream” anthology of Renaissance poetry?

Cristina Neagu: Browsing through various Renaissance anthologies of poetry published during the last fifty years, particularly anthologies of Neo-Latin verse, one is bound to quickly discover the absence of any poem by Nicolaus Olahus. Not an auspicious starting point for our discussion, it would appear. However, the fact that his name is not included should not surprise. Olahus is no longer remembered as a household name, and, as a consequence, one has to dig deep to revive and return him to the limelight he once basked in. The editor of any Renaissance anthology of poetry published these days has a distinctly difficult task. Usually, the two main criteria for selection are focus on literary excellence, and range. Since the language of choice is Neo-Latin in our particular case, excellence translates into the ability of an author to create exceptional verse in a wide variety of genres and styles, confidently approaching the vast diversity of themes that flourished at the time. As to the range, this covers practically all Europe from the 14th to the 17th century. But while Neo-Latin, as a more self-consciously ‘classical’ form of Latin (as opposed to what is described as ‘medieval’ or ‘scholastic’ Latin) can be defined in terms of chronology and broad geographical distribution, things are further complicated by the fact that authors then not only moved easily between genres and disciplines, but also took great delight in swerving expression between their various mother tongues and their use of Latin. And speaking of Latin, one should always remember that, for a very long time, it was both model and competitor for the up and coming vernaculars, and it also was the international language all over Europe and beyond. This might explain why Neo-Latin anthologies of poetry, more than any other anthology or miscellany, tend to showcase expression of scholarly thought in poetic form, and usually provide the reader few surprises, opting for a more or less expected selection of familiar names.

With this in mind, now, let us briefly turn to Olahus’s poetic attempts. To start with, commentators will find themselves in the privileged position of having access to almost all of his poetry transcribed in just one manuscript, the so-called ‘H-46’Codex carminum Nicolai Olahi, kept at the Egyetemi Könyvtár in Budapest. Apart from this, seven of Olahus’ poems also appear in the printed text of the 1537 edition of D. Erasmi Roterodami epitaphia, per eruditiss. aliquot viros. Variants of some of the poems can also be found in the Viennese ‘Sign. Lat. 8739’ manuscript of the Hungaria-Athila, kept at the National Bibliothek, and in the manuscript marked ‘P.108. Rep.71’Epistolae familiares Nicolai Olahi ad Amicos kept at the Magyar Országos Levéltár also in Budapest.

The corpus of Olahus’s poems contains four distinct groups. The first category consists of five poems on the death of Erasmus and two epitaphs for Thomas Szalaházy, Bishop of Veszprém. As I’ve said, the verse dedicated to Erasmus also appears in two manuscript versions and an edition, and is relatively well documented. The second group includes three poems written under the impact of the death of his brother, Matthaeus. These were collected together with other verse and sent to Olahus by his humanist friends in the Low Countries to comfort him in his loss. Sources contemporary to Olahus suggest that the collection was published by Petrus Nannius in a single volume. Unfortunately, the edition (if there was one) seems to have been lost, so, the only source for these poems is the Codex carminum. Thirdly, there is an important poem which served as a preface to Olahus’s chorography, the Hungaria-Athila, which, apart from the Codex carminum, can also be found in the above-mentioned Viennese manuscript. Finally, there is the corpus containing all the above (minus the epitaphs for Thomas Szalaházy), plus the rest of Olahus’s poetry compiled in the Codex carminum. Although not particularly beautiful, or catching the eye in any obvious way, this Codex carminum is a manuscript of utmost importance, which has a lot to do with your question regarding the presence of Olahus’s verse in Renaissance anthologies of poetry. To which my answer is ‘yes’! Despite his resounding absence from present day publications of this kind, Olahus’s poems were included in collections of verse issued by his contemporaries.

One such anthology is the above-mentioned 1537 volume put together by Rutgerus Rescius at the death of Erasmus. While the number of poems in honour of the humanist far exceeds everything else, the collection is essentially eclectic in nature.

The other anthology that stands out inviting careful scrutiny is the very Codex carminum cited before, this rather plain manuscript the significance of which cannot be over-stated. Like the 1537 edition, the Codex carminum is also an eclectic collection. Of course, it principally collates Olahus’s poems, but it also contains verse responses to individual poems by such authors as Cornelius Grapheus Scribonius, Franciscus Craneveldius, Jacobus Danus, Ursinus Velius and Petrus Nannius. In addition to this, there is a large number of poems dedicated to Olahus by other humanists, including Nicolaus Istvánffy, Jacobus Piso, Sebastianus Listhius, Joannes Sambucus and Franciscus Forgách. Given the presence of a group of epitaphs on the death of King Ferdinand, the volume was probably collated after 1566. The transcription of the poems was almost certainly done in Olahus’s chancellery, as the sections containing verse by Olahus are written on the same kind of paper as that used for several documents he issued as Archbishop of Esztergom, between 1553 and 1563. Considering its strictly functional appearance, and given the effort to collect and copy so large a corpus of poetry, plus taking into account the presence of corrections, this may have been a volume in the preliminary stages before publication, which sadly did not happen. But, by the looks of it, we know what it was meant to be: an anthology of poetry typical of the period when it was created.

Here I have to point out that, at the time, anthologies were not yet perceived as a discrete genre, but even so, they were a recognizable category of early modern book emerging out of the medieval practices of compilatio. Of course, each volume has its own complex history. Before reaching the press, it would have gone through many stages of compiling, from gathering and selecting the verse, to designing the book’s structure. All complex and time-consuming. Plus, one quickly realizes that, while the practice of editing is visible in most anthologies, the Codex carminum included, one can rarely speak of a recognisable editor, in the modern sense of the word. So, summing it all up, a Renaissance anthology of poetry, as it was perceived at the time, is best understood as a book in process, a dynamic structure of selecting and organising verse the main purpose of which was transmission. In other words, such anthologies, more than any other genre, were regarded as an antidote against forgetting. A means for the selected authors to stay alive and remain relevant. Looking now at Olahus’s poetry as preserved in the Codex carminum, with the help of a number of lucky breaks in the course of its history, it reached us exactly as it was meant to: open to our scrutiny, inviting questions, offering some answers… but definitely not all the answers we might seek.

As to whether this poetry did better in terms of the ideas conveyed, or through its aesthetic value, well, it has to be both. In order to make an impact through the ages, it has to be well put together, and preferably original both in content and in form. In Olahus’s case, I believe that it is. When one looks at the hefty and wide-ranging corpus of poems he worked on, there is one feature which gives it a significant degree of coherence and unity: it invites analysis in terms of rhetoric, and more specifically, the three rhetorical genres. Consistent with fashion and the expectations at the time, most of Olahus’s poetry follows the rules of laus and vituperatio, characteristic of the genus demonstrativum. The Carmina also contains a series of epistles in verse, in which the style is based mainly on the conventions of the genus deliberativum, and elements recalling the technique of the genus iudiciale can be identified in poems such as the preface to the Hungaria-Athila, in which the author defends what he calls his ‘unpolished style and lack of linguistic excellence’. So, the whole gamut of rhetorical devices is at work here and Olahus makes sure to fully test his readers in this respect.

Robert Lazu Kmita: Bringing Olahus’s poetic corpus out of the shadowy cone in which it currently resides can be achieved, on one hand, through the publishing and dissemination of his works. However, today there are also digital means whose adaptation in the service of culture you have been working on for years. What has been done in this regard for Olahus? Are his works accessible online – both in the original and in translations?

Cristina Neagu: Broadly speaking, the state of Olahus studies at present is encouraging. His works have been addressed in important critical editions, many accompanied by admirable translations into English, Hungarian and Romanian, mostly. In this context, I must point out the excellent ‘Nicolaus Olahus, Opere’, issued by the Romanian Academy in 2023. It includes all the humanist’s works in the original Latin and translated into Romanian, with copious notes and a solid introduction. Other outstanding recent publications tackle parts of Olahus’s impressive output. To give an example, this is the case of Emőke Rita Szilágyi’s work, especially that connected to the humanist’s propensity for the epistolary mode of expression. To start with, the editor discovered previously unknown letters. As a basis for comparison, while the Epistolae familiares – Ipolyi Arnold’s 1875 reference edition for Olahus’s correspondence – contains 609 letters (selected by the humanist himself), Dr Szilágyi’s includes a total of, at least, 1,375 letters. The result is a remarkable critical edition of Olahus’s correspondence, in 2 volumes so far (the third volume is expected in 2027), available both in print and as an e-book. And, to complement all this, Emőke Rita Szilágyi has also embarked on coordinating the efforts to create an online platform for Olahus’s correspondence as well. This is not quite ready yet, but can already be consulted. These sort of platforms, allowing various types of searching, and their access to digitized manuscripts, are exceptionally useful for large collections of letters, as they reveal a wide and vibrant network of relations between correspondents, and can be updated with new discoveries. As to other projects involving Olahus’s manuscripts that are being digitized, there is an ever growing number of them made available though the Hungarian National Archives. To find the corpus in question, one needs to choose the view “Hierarchia”. Listed on the left side are the Funds available for consultation at present. “P 184” contains the letters of the Olahus family.

Robert Lazu Kmita: If Olahus needs anthology coordinators to include his poems in the current readership circuit, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is already well known to all educated readers. Currently, you are involved in a project precisely related to the digitalization of his works. How did you move from Olahus to Dürer? Were these two authors simultaneous focal points in your academic interests, or was there a transition?

Cristina Neagu: You are right, I was involved, as you say, in adapting digital means in the service of culture. This now makes the transition to the Dürer project, that I am currently working on, smooth and organic. Indeed, for many years, while working as Keeper of Special Collections at Christ Church, among many other things, I was in charge of a particularly ambitious project. The aim there was to produce high-resolution digital copies of every manuscript and unique or very rare item in the college’s core collections. We are talking here of thousands of items tagged for digitisation. This is obviously—and will be for quite a while—still work in progress. It will take time, resources and determination to bring this particular project to fruition. However, a great number of documents are already available for consultation on both the Digital Bodleian platform and the college Digital Library website.

Creating a Digital Library for Christ Church Special Collections was a very different type of job if we compare it to the one I am currently engaged in. The project involving Albrecht Dürer’s correspondence (as part of EMLO) stands out in a class of its own. Essentially, EMLO (otherwise known as Early Modern Letters Online) is a huge union catalogue for letters exchanged during 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century Europe. A sophisticated and multifaceted software developed at the University of Oxford brings manuscript, print, and electronic resources together in one space, and allows both disparate and connected correspondences to be cross-searched, combined, analysed and visualized. This entails the collection of unprecedented quantities of metadata, and the standardization of the means of describing and processing them. It also calls for collaborative work on the development of both new digital tools, and new scholarly methods able to get to grips with a colossal field of research. I say this because correspondence was what we might rightfully call the information superhighway of the early modern world. Between 1500 and 1750, intense exchanges of letters encouraged the formation of virtual communities of people with shared interests which stretched across the globe. Philosophers, classical scholars, philologists, politicians, antiquaries, theologians, artists, mathematicians, astronomers, botanists, all cultivated and sustained their professional and intellectual lives in and through writing to each other.

Nicolaus Olahus and Abrecht Dürer are, each in their own way, rather inspiring examples of a trend that was quickly finding firmer and firmer ground. This new age of letter-writing came with the rediscovery, in the 14th century, of the correspondence of Cicero and Pliny. The emergence and unparalleled success of the 15th-century editions of their letter collections was radically to change perceptions of the genre.

That Olahus was acquainted with this profound change in the art of epistolography is confirmed in part by the presence of the Latin translation of the Epistolae Graecae elegantissimae among the books traced from his personal library. Emulating a tradition which Erasmus developed to hyperbolic dimensions, Olahus too devoted many hours to the reading and writing of letters. A huge number of these can already be accessed consulting Dr Szilágyi’s remarkable work on Olahus’s correspondence which is now linked to the EMLO platform as well.

You ask me about moving from Olahus to Dürer. I can’t say that I have switched from one to the other. The German painter has always been high on my list of favourite subjects, and I wrote several studies mainly focusing on the interplay between image and written language as one of the main features of Dürer’s style. The first of these studies was in preparation for a talk I gave at the Renaissance Society of America conference in Florence, back in 2000.

When compared to his achievements in the visual arts, Albrecht Dürer’s written output may seem unimportant. However, not only did he cultivate various literary genres with enthusiastic confidence, he also consciously integrated the fluidity of written expression within the space of his pictorial and graphic works. In this context it should not be surprising to realize that the artist was also an avid letter-writer. In fact, more letters by him survive than by any other German artist of his time. And although it is clear that they make up only a small fragment of what he wrote, they provide us with invaluable information about the friendships he cultivated, the struggles and ambitions that shaped his career, his desire to learn new things, to push the boundaries of knowledge as much as was humanly possible. Collating, transcribing, translating and commenting these letters is currently one of my priorities research-wise. They have started becoming available on the EMLO platform (link to be shared shortly).

Robert Lazu Kmita: We have discussed all the main aspects of your work and that of your colleagues. A work that, today, allows (almost) instantaneous access for a huge number of readers and researchers to all these cultural treasures. Now, at the end of our conversation, I really want us to focus on the heart of the matter. Because, after all, all your work can only find fulfillment in the content of the interpretations that result, for example, from reading Durer’s correspondence. What can all these sources bring to the public–both the restricted audience of specialists and the broad audience of passionate readers from everywhere? More specifically, what are those ideas that have been “revealed” to you throughout your work? I would be glad if you could even present a couple of personal discoveries that have illuminated the meanings of Durer’s artistic creations.

Cristina Neagu: I have a short confession here. I came across Dürer’s correspondence by sheer accident. It was many, many years ago. I remember my eyes falling on one of the books my father had just bought: a selection of texts by Albrecht Dürer. At that time I only knew Dürer as a painter and engraver. Intrigued, I picked the volume up and from the moment I opened it I couldn’t let go until the end. It wasn’t a very big book, so the end came frustratingly fast. However, despite the fragmentary nature of the selection, the few texts included in the volume were definitely fascinating. And my reaction to reading these texts surprised me. Especially when reaching Dürer’s correspondence with his friend Willibald Pirckheimer. In my heart, I can still hear myself laughing out loud, captivated by the extraordinary voice, so clear and immensely witty from behind the printed page. As I said, my first meeting with Dürer as a writer happened a long time ago, but ever since I have been secretly waiting for a chance to explore this voice in ernest. So, I quickly jumped on board when the opportunity arrived for me to focus on researching Dürer’s correspondence preserved in various European archives for the Early Modern Letters Online project.

One of the first things to notice is how extensive and rich this correspondence between the artist and his contemporaries was. It takes a wide variety of forms: from personal missives, letters of official business, sometimes even poems, to scribbles accompanied by drawings. These attest to relationships based on a shared sense of humour, a love of learning, a commitment to devotional practice, and, perhaps most of all, a sense of mutual respect. Among the best known examples are ten letters that Dürer sent to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer from Venice. To these we need to add the nine letters that the painter wrote to Jacob Heller concerning the altarpiece he commissioned for the Church of the Dominican monastery in Frankfurt am Main. Very exciting and providing a huge amount of information is the exchange between Dürer and the other artists involved in projects commissioned by Emperor Maximilian. All these needed a great deal of preparation and agreement. How this was achieved shines through the dialogue carried out by the artists involved via an unmistakably substantial correspondence. There is also a great number of letters on the topic of the painter’s annual stipend addressed to the Council of the city of Nuremberg by Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V, and by Dürer himself. Apart from all these, one can also find exchanges involving some of the most influential political figures, scientists, humanists, and religious leaders of the day. All in all, an impressive number of documents to plough through.

The bulk of these are now located at Stadtbibliothek in Nuremberg. Further material is also found at Kunstmuseum Basel-Kupferstichkabinett, British Library, Royal Society, Universitätsbibliothek in Basel, Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne, Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam and the Albertina Museum in Vienna. A great number of priceless manuscripts has been digitised. Large sections of documents by and about Albrecht Dürer’s written input are now made available through the Heidelberger historische Bestände – digital. This is an extraordinary resource. It is true, the large majority have been attentively edited in Hans Rupprich’s monumental Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass (Berlin: 1956-1969). However, being able to see autograph manuscripts is essential. This does not only bring contextual and bibliographic extra-information. It also reveals something of the reality and voice of the person beyond the text.

Let us, for instance, take the case of the letters Dürer dispatched to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer. Looking at the originals will immediately unfold details such as the quality of the paper and its likely provenance. They will also show marks of how letters were folded and secured, and where the name of the recipient and destination were written. Thus, from the latter’s position and orientation we learn that there was no separate envelope. Just a special way to tuck the paper properly. To read a letter, the recipient had to tear a strip woven through slits in the page, or break the seal that fastened parts wrapped together. Looking at the manuscripts, one is also bound to notice that, as a rule, Dürer would fill the pages from top to bottom in continuous lines without paragraph breaks. Depending on whom he was addressing, whether he was engaged in putting together an official letter or he was jotting down an informal missive to a close pal, his handwriting would change from neat, tidy, almost calligraphic, to hurried, nervous, displaying huge inconsistencies in orthography. He was aware of this. He even urged his reader to forgive his mistakes and focus on the content he aimed to convey. Facing pages like these is quite an experience. And it can only be gained from seeing the autograph manuscript. Looking at details like the ones mentioned above, one can almost sense the speed of Dürer’s thoughts, and his frustration of not being able to manifest them on paper quickly enough. Words are thus fluid, changing shape and pronountiation varies widely. Vernaculars are Dürer’s languages of choice. Not the customary Latin of the day. And not just his native German he embraced with gusto. In quirky, extravagant gestures, Dürer would also occasionally sprinkle his more informal letters with paragraphs written in bad, but entirely entertaning Italian. Overall, his use of language is often perplexing, and one is left wondering wheather this often garbled language, with its crude orthography and grammar, reflects what was an essentially oral command of the vernaculars, or whether its intended ineptness is part of a deliberately comical repartee, a mode of expression meant to arouse amusement. Most likely, it was both.

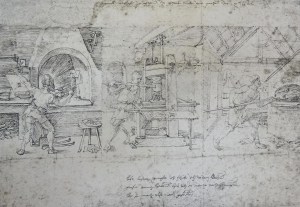

And Dürer being Dürer, words were on numerous occasions not enough. Ever so often drawings are an integral part of his letters (see Figure 1). And to have full grasp of their content, one needs to really see them as they came out of Dürer’s hands. Therefore access to his manuscripts (in original or digitzed version) is a must. To prove my point, let me take a short message written on a rather intriguing drawing and dispatched by Dürer to his friend and close neighbour Lazarus Spengler (see Figure 2). I admit, this is a rather extreme example.

A sheet of paper, about the size letters would normally be written on highlights a drawing in the centre and two sections of text above and below it. The writing is small and looks hurried. Beneath the image Dürer wrote: ‘Dear Lazarus Spengler, here I am sending you the flatbread. Have been much too busy and could not bake it sooner. Hope you enjoy it!’At the top of the drawing, the text goes: ‘Such puffed up letters: they are being cast, printed, and baked. In the year 1511.’ The translation is from German. The drawing shows what look like pieces of paper being handled in a blacksmith’s shop, then printed in a press, and finally baked in an oven. All rather intriguing. At least for us, now. And like many good puzzles, this document has caused many scholars pause and try to figure what the artist meant to actually say. According to Shira Brisman, for instance, this letter draws upon a mutual understanding between friends who distinguish between skill and invention, reproduction and originality, publicity and intimacy, production accomplished in haste versus creation that takes time. Dürer’s words liken his drawing to a baker’s confection, just as the drawing itself portrays Spengler’s craft, the preparation of correspondences, as raw dough for the oven. Harold Grimm’s interpretation is different. He links it to the moment when Hieronymus Holzschuher and Kaspar Nützel turned over to Spengler the writing of reports to the Nuremberg City council while they were away on diplomatic missions. This happened in 1511 and it was at this time that Dürer presented his friend with the drawing portraying these three men (represented by the blacksmith, the printer and the baker) whose job was to prepare official reports for the City council. The drawing highlights the printer, apparently Spengler, who uses a book press to affix with vigor his seal on the documents. Alan May goes even further and, delving deep into the drawing, manages to bring to the surface some of Dürer’s secrets related to how he developed his printing press, improving on Gutemberg’s patent.[*]

There may be all sorts of other possible interpretations for this and several of Dürer’s letters that have survived, and access to his manuscripts, together with good critical editions, help us ennormously get closer to rich, multifaceted texts. But, it seems to me, in Dürer’s case at least, there will always be a deeper secret for us to fathom. However, what we know for sure is that, while difficult for any external parties to understand, the meaning of Dürer’s message must have been less of a problem for his contemporaries and definitely his immediate circle of friends would have been able to get the gist right away. In fact, this witty interplay between deliberatly baffling words highlighting often intriguing images surfaces again and again in so many of Dürer’s works. Even his most discussed and celebrated masterpieces.

Take for instance the Self-Portrait of 1500 (see Figure 3). This is without any doubt one of the most fascinating and studied of his works. It is also unique in the art of his time. It is very daring, and, at first sight, it looks boastingly self-assured. Its hieratic composition and the hand placed in an obvious gesture of benediction suggest the artist deliberately stylized himself into the likeness of Christ. What we have here is one of the clearest representations of man as imago Dei. In its christomorphic quality this portrait recalls the style of Byzantine icons and the tradition of the acheiropoieta. Although tenuous at first sight, there might be the suggestion of a subtle link between these and Dürer’s self-portrait. In Byzantine iconography the idea is that, essentially, icons are not created by man. They are images directly reflecting the divine. Looking at this particular self-portrait is a rather unique and mesmerizing experience. While, on the one hand, the viewer is clearly invited to accept the imago Dei interpretation, on the other hand, the inscriptions that Dürer placed so obviously within the pictorial space channel us away from a reading giving the sacred dimension too much credit. What are we to make of this? Obviously, that Dürer attempted his own commentary to the otherwise very common formula of imitatio Christi. Also that in dealing with ‘self’ as a subject of painting, and the concept of art as a matter of genius, he implied a mystical identification of the artist with God. All this is true. But this alone cannot explain much in terms of the power that this painting has over the viewer. What is it that draws us so irresistibly towards an almost monochrome portrait? What happens when we focus on this particular image? Our eyes are caught by the vertical pointing upwards from the index finger of the right hand to the eyes of the character. This is an unambiguous reference to the power of sight and, perhaps, the underlying impact of visual art. What happens next is the artist taking us a step further and directly into a world steeped into Neo-Platonism. On the horizontal, following the same line with the eyes are two inscriptions. On the one side is Dürer’s monogram and date (1500), on the other, in beautifully calligraphed Latin, is the following text: ‘Albertus Durerus Noricus/ipsum me proprijs sic effin/gebam coloribus aetatis/anno XXVIII’. In translation: ‘I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg, painted myself with indelible colours at the age of 28 years’. As viewers, we are urged to read. Reading takes a while, as we must not only engage in taking in the sounds that make up the letters and figures involved, we also have to translate them into a language that we are more familiar with. In other words, we are invited to consider dwelling on the painting’s both spatial and temporal dimensions. Reading the inscriptions like a text, from left to right, we pass from the year 1500 to the artist’s monogram, which, significantly in this case, can be simultaneously translated into ‘anno domini’ (1500 AD), thus conferring further unity and weight on the date as a special moment in time. The text continues on the other side of the image, unfolding the meaning of the monogram and the artist’s age. Thus, it super-imposes individual chronology over the main point of reference, 1500 AD, i.e. a date charged with special significance, ‘as agent and emblem of a new seaculum’. By doing just this, the text replaces the myth of divine production in illo tempore and establishes the authenticity of a specific work of art and an individual artistic self. Furthermore, in a powerful and unambiguous confession, encoded deep within the letters grafted onto the image, the artist allows the viewer to have a glimpse into the very process of creation, the ‘divine frenzy,’ the poetic madness that makes it possible at all. In an unprecedented gesture, the artist has decided to actually empower his viewers. We are urged to look as well as to voice the painting, to see as well as to listen to it. Only this way, it appears, will we be able to conjure up all its meanings and beauty.

In relation to art, as much as in relation to poetry, we have to accept the wisdom of sound, with all it entails: from word to number, from language to the music of spheres. It is within the special framework of ‘indelible colours’, as Dürer puts it, of colours depicted in time, often by means of the power of words, that we should learn to look at his work. In a draft for the introduction to a book on the art of painting which he was planning, Dürer said: ‘This art of painting is made for the eyes […]. A thing one holds is easier to believe than a thing one hears. But whatever is both heard and seen we grasp more firmly and lay hold of more securely. I will therefore do the work in both ways that thus I may be better understood.’ The source of the Dürer fragment is a manuscript written in a hurry, a rather messy-looking piece of paper full of additions and corrections, currently kept at the British Library. It was among Dürer’s manuscripts purchased from the Imhoffs by Amsterdam merchants around 1635. It reached London when five leather-bound volumes were presented to the British Museum as part of Hans Sloane’s foundation bequest in 1753. Dürer never got to finish his planned treatise on painting, so, access to this, and other, extraordinary repositories of words (containing letters and a huge number of variants and drafts for written works, both published and not) is a godsend, the golden ticket we need, as it gives us a chance to better figure out the artist in all his fascinating complexity. What joy and privilege to follow his thoughts as reflected in paintings, his graphic art and his drawings, while also delving deep into so much uncharted territory brought to life by the power of his words. No wonder he was so careful to organize and archive his manuscripts, from drafts and versions of his published works to bits of paper scribbled in apparent haste. All his life he was careful to keep his words close by. As were his friends careful to keep his letters. Not all survived. Far from it. But enough did, for us to be able to hear his voice now.

This interview was conducted on May 3, 2024.

[*] See Shira Brisman, ‘The image that wants to be read: an invitation for interpretation in a drawing by Albrecht Dürer.’ Word & Image, 29(3), 2013, pp. 273-303. Harold J. Grimm,’Lazarus Spengler: A Lay Leader of the Reformation (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1978), p. 28-9. Alan May, ‘Albrecht Dürer’s drawing of a printing press: a reconsideration.’ Journal of the Printing Historical Society, New series, 22, 2015, pp. 62-80.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Self-Portrait with Fur-Trimmed Robe” (1500) by Albrecht Dürer, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News