We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Two composers, two works, separated by four centuries, and the way Ralph Vaughan Williams managed to blend the two sensibilities is amazing. And here I am, listening today, and it takes me on a journey, not just to 1910 when the “Fantasia” was composed, but back to the time of Tudor England when Thomas Tallis had to hide his Catholicism because it had been outlawed. His innate spirituality flowed forth, and I can feel it.

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis is gorgeous, ethereal and, I came to discover, difficult to capture in words. Out for dinner the other night, I confessed to my husband that I was having trouble getting my essay about it off the ground. It was so clear in my mind, the allure of the composition, the austere beauty of Thomas Tallis’ 16th century psalm tune on which Vaughan Williams had based the Fantasia. But every time I tried to consign my thoughts to paper, they fled. For days now, I’d listened to both compositions over and over, helplessly entranced but helpless to move forward.

My husband munched on his pulled-pork sandwich as he considered my words. “How about we try the ‘three why’s. Why does this subject compel you?”

Why was I so compelled to analyze and elaborate on the significance of this piece? I shut my eyes and began. “Because it contains two layers of musical genius. I mean, it’s two composers, two compositions, almost 350 years apart.” I opened my eyes. “The 16th-century guy was Catholic and composed choral works in the time of Henry the Eighth and three more monarchs—they were mostly Protestant and anti-Catholic. The 19th century guy, Ralph Vaughan Williams, even though he was an agnostic, still found this deep interest—I’m sure we can call it spiritual inspiration—in English choral works, of which guy No. 1, Thomas Tallis, was the master.”

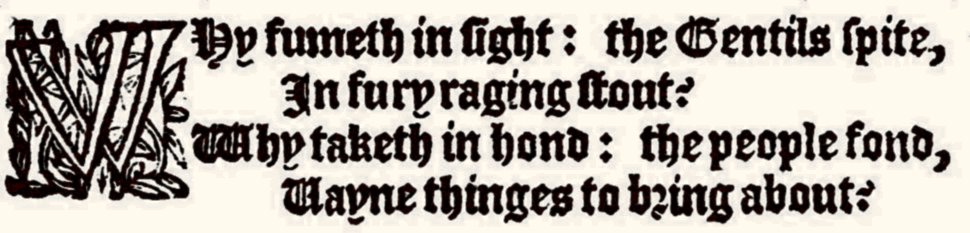

I’d learned, from researching this essay on Ralph Vaughan Williams, that he’d labored from 1904 to 1906 to edit The English Hymnal for the Church of England and it was surely here that he’d found himself so drawn to Tallis’ vivid, fiery “Why Fum’th in Fight?” The piece lasts only fifty seconds, but it’s instantly haunting and unforgettable. Where did this mood come from?“Yes, but why?” my husband asked.

Stirred from my reverie, I regarded him, perplexed, over my burger and onion rings. “Why what?”

“Why is this interesting?”

“Because… because it’s art,” I sputtered. “Really good art. And all good art compels you to study it from all angles, trying to decipher the alchemy that made it all work so seamlessly. It invades your senses. I can’t not analyze it.”

“Why?”

His glib attitude was starting to frustrate me. “Because I know there are music-loving readers out there, trying to figure out this puzzle too. And this is a two-for-one! Two composers, two works, and the way Vaughan Williams managed to blend the two sensibilities is amazing. Not to mention the Fantasia was created over 100 years ago. And here I am, listening today, and it’s like it takes me somewhere. A journey, not just to 1910, but back to the time of Tudor England when Tallis had to hide his Catholicism because it had been outlawed, but his innate spirituality flowed forth, and I can feel it. And I want others to take this journey of the mind too. Not just of the mind. The senses. The spirit.”

“Okay,” he said amiably.

“Okay?” I repeated warily, having girded myself for more interrogation.

He reached over and took one of my onion rings. “Sure. That was the ‘three whys’.”

I’d forgotten about that. “You mean that was just a mind experiment?” I protested.

“Did it work?” He popped the onion ring into his mouth.

I sighed. “It did.”

I realize that when we speak, storytelling and discerning the story’s essence arise naturally. I love stories. I love music that tells a story, even though it doesn’t have words or characters. It’s the setting of a scene, a trajectory, that I find so important, which is why atonal music provides limited appeal to me. If I can’t “see” a story, I lose interest. Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585) had a natural advantage here; his story was a Biblical psalm he’d been assigned to set to music. And as for RVW (you get that this stands for Ralph Vaughan Williams so that I don’t have to write his name out every time, right?), this composition in question came well before the cinematic The Lark Ascending (written in 1914, arranged for orchestra in 1920), so he hadn’t acquired that “storytelling” aspect to his compositions yet. Or, better put, this was where the magic in his music started.

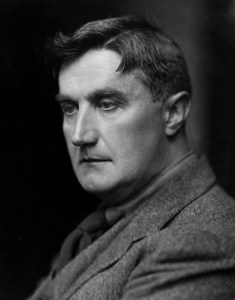

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958), born to an illustrious family, had a genteel upbringing that I elaborated on here. At seventeen, he commenced studies at London’s Royal College of Music (his preference), departed a few years later to study and earn degrees in music and history from Trinity College, Cambridge (his family’s preference), then returned to the Royal College of Music to complete those studies. But this second-time-around professor of composition, Charles Villiers Stanford, embraced the highly popular German sound and sensibilities of Brahms and Wagner, which RVW kind of resisted. He found more inspiration in going out in the field with his friend and fellow student, Gustav Holst, to research and retain the traditional English folk music they both admired. Completing his studies, he began to produce worthy compositions, while working as well to edit The English Hymnal. But he still felt as though something important was missing from his work. So he headed to Paris in the winter of 1907-08 for a three-month intensive with Maurice Ravel, who turned down students constantly but had agreed to work with RVW. There, what Ravel helped him find was a clarity of texture in his music, a luminosity of orchestral sound. Best of all, Ravel’s tutelage helped eradicate the Teutonic influence that RVW felt hindered British classical music from sounding “British” enough.

Bingo. It was the magic key. RVW went back to England a fully realized composer.

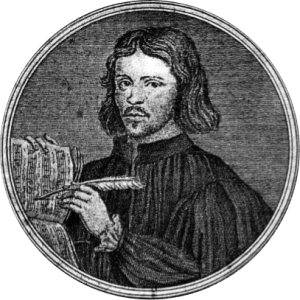

I’m dying to have you listen to his 1910 Fantasia, but let’s first jump back another 343 years to Thomas Tallis, who served four English monarchs during a long, productive career. He was an organist at Waltham Abbey until Henry VIII shut it down in 1540, like he’d done to all the monasteries. Tallis was a devoted Catholic, but the once-Catholic Henry VIII had established his own Church of England once the Pope excommunicated him for divorcing Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn, and it became decidedly un-PC to be a Catholic.

Tallis knew how to play his hand carefully, serving through the reigns and political/religious turbulence of not just Henry VIII but Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. The newly crowned Elizabeth quickly established the Religious Settlement of 1559 (in the wake of her predecessor’s fierce Catholicism), which enforced the Protestant religion by law, but she benignly looked the other way when Tallis allowed his Catholic sensibilities to arise through his music.

Let’s fast forward to 1567, when the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, began compiling a psalter consisting of 150 Old Testament psalms, rewriting them as English metric verse. He invited Tallis to contribute nine tunes, because by that time, Tallis was the master for choral compositions, having also played a big part in introducing polyphony into English music. Tallis’ nine psalm tunes are fascinating to listen to; I wonder if I’m partial to them because I’m Catholic. Hearing them, I slip instantly inside a familiar, sacred, timeless world that calms and assures me.

Something else to note: the third psalm was composed in the Phrygian mode. Modes, a type of scale, have been around since the Middle Ages, although, regrettably, we rarely hear them in contemporary Western music. For the record, the modes are: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian. Each mode begins on a different note of the scale, such as E to E (Phrygian mode) or C to C (Ionian mode), which gives each mode its own character. The Phrygian mode is also known as the “third mode” and “the Spanish gypsy scale,” because it resembles the scales found in flamenco music.

Now’s a good time to give Tallis’ “Nine Psalm Tunes” a listen, performed here by the Tallis Scholars. The words are written below. Slow down and listen again. And again. You’ll find the all-important third psalm at 1m43. Although if you’re like me, it will announce itself to you, leaping out and seizing you by the heart, compelling you to listen to it again and again. I can’t count the number of times I’ve listened to the third one. It’s a big, embarrassing number.

Why fum’th in fight the Gentiles spite, in fury raging stout?

Why tak’th in hand the people fond, vain things to bring about?

The Kings arise, the Lords devise, in counsels met thereto,

against the Lord with false accord, against His Christ they go.

Here is the original Psalm 2: 1-2, from the King James Bible:

Why do the nations rage,

And the people plot a vain thing?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

And the rulers take counsel together,

Against the Lord and against His Anointed…

Am I right about the third tune? It stands out like a gem amid the others. It has power and passion. Even Archbishop Parker thought so, stating that “The third doth rage: and roughly bray’th,” which is so cute, I chuckle every time I think of a 16th-century Archbishop, in robes and miter, admitting, “Forsooth, it doth roughly bray’th and putteth meself into a fine, feisty mood.”

And now, without further ado, here is the main feature. Arranged for double string orchestra and a solo string quartet, it blends RVW’s evocative originality with Tallis’ devotional sensibilities. The sound of shimmering strings, the orchestra’s lush, full response (thank you, Ravel!), a plaintive solo viola and violin line, and all the rich textures in between add up to make it simply stunning.

Enjoy this performance of the New Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Prepare to be transported. Prepare to catch a glimpse of history, even, perhaps, the divine.

Thomas Tallis owes Ralph Vaughan Williams a debt of gratitude, for bringing him recognition and fame well beyond England and the world of 16th century choral music. Or maybe it’s that Vaughan William owes Tallis the debt. For Tallis having composed music fit for his time and centuries beyond, so memorable that RVW returned to it four years after his editing work and decided, this one. This is it. I can’t not.

I can appreciate the feeling. It’s why I fought against vagueness, overwhelm, writer’s block, what have you, in order to finally write this piece.

This one. This is it. I can’t not.

***

This post is dedicated to the memory of my dear friend, Grace Harstad, who passed away on August 22, 2021.

Republished with gracious permission from The Classical Girl (September 2021).

This essay was first published here in October 2021.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay. The portrait of Thomas Thomas is a detail of an 18th-century posthumous engraving by Niccolò Haym, after a portrait by Gerard Vandergucht, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of Ralph Vaughan Williams is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of Parker’s verse for which Tallis composed the tune used by Vaughan Williams is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News