We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s is a Messianic view, but devoid of God, regarding Superman both as saviour and saved. His concept led to the justification of violence, cruelty, the worst inequality of human conditions, and even slavery. There has been in our age no more complete embodiment of the satanic rebellion.

The Church of the Revolutionary Age: A Fight for God, Volume 1, by Henri Daniel-Rops (Cluny Media, 284 pages)

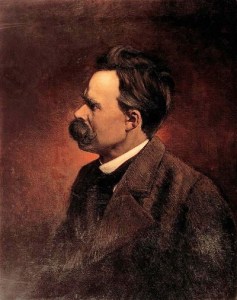

Friedrich Nietzsche. I cannot speak without affection of this man, whom the atheistic world acknowledged as one of its guides. He loved nature, animals and flowers; delighted in the thought of Italy and Greece; found in music the satisfaction of a vital need; and was among the greatest German poets, disciple and rival of Heine and of Hölderlin. Though he believed himself to hate goodness and mercy, he was good, compassionate towards the humble and the poor, so gentle in behaviour that his neighbours at Geneva used to call him “little saint.” But above all—and this is why no Christian can look upon him with indifference—he committed himself entirely to that battle with the Angel, which every man must fight, regardless of risk, knowing that he endangered more even than his life, face to face with mystery in an almost Pascalian agony, bearing witness to our worst temptations.

Let us watch him as he stands beneath the rock of Surlei in the Engadine, looking out across the cold blue lake of Sils-Maria, finding himself “six thousand five hundred feet above sea level but far higher above all human things,” overwhelmed by a flood of wellnigh unutterable intuition, yet experiencing to the point of delirium a longing to proclaim his revelation. Hegel and Feuerbach, Comte and Renan, Spencer and Stuart Mill, all those doctrinaires of unbelief, were dreary intellectuals, logicians, teachers. Nietzsche was otherwise; he rejected them all with contempt: rationalists and positivists, materialists and idealists, and socialists as well. He wanted nothing to do with logical demonstration. What he had to give the world was an existential certitude that had suddenly taken shape within him, in a moment of miracle and anguish. And he knew that a terrible secret had been entrusted to him. “I would rather be a lecturer at Basel than be God,” he cried; “but I am too much of an egoist to refrain from creating the world!” He had the look of an inspired prophet; with his enormous brow, huge moustache and deep-set feverish eyes, he might have been painted by Michelangelo on the walls of the Sistine. Did he not call himself “prophet of a darkness hitherto unknown”? Modern irreligion was to have no more pathetic voice.

Can we, with reference to Nietzsche, speak of a doctrine? He was subject to so many influences: those of Heine and Dostoyevsky, which he accepted; those of Strauss and Feuerbach, which he rejected; that of Richard Wagner, which he likewise scorned. In him there was something; of Mani, something of Buddha, something even of Christ, many of whose sayings were twisted by Nietzsche into aphorisms of his own. Nothing is further from a systematic approach than the way in which he expresses himself through strings of lyrical maxims and lapidary phrases, all of which are in shameless contradiction one with another. It is easy to quote him in support of every thesis, even of those which form a traditional part of Christian apologetics. Where for him do paradox and irony begin; or where the need to cry the most scandalous of truths? And yet from that teeming medley there emerges a true philosophy, if we accept “philosophy” as meaning an attitude towards life. If there is no Nietzschean system, there is certainly such a thing as Nietzschism.

The fundamental principle adopted by this Thuringian pastor’s son was radical unbelief. “For me,” he wrote in Ecce Homo, “atheism is not a result of something, still less an event in my private life; it is of course instinctive.” Small matter that one sometimes suspects this avowal of being forced, arbitrary, and that the God whom he pretends so serenely to dismiss remains for him an opponent, terribly real and close. It is from this assumption that all his theories derive: there is no God, heaven is empty, thus saith Zarathustra.

The first consequence of such an axiom is that there can be no religion. According to Nietzsche religion comes of man’s “doubling” himself. Among the strongest there comes about an awareness of human grandeur; but this dare not give expression to itself, and ends by conferring the attributes of man upon a supernatural being. These attributes of divinity are such as the weak and second-rate can never possess. Religion is thus in every respect an “alienation of personality,” “a negation of man’s greatness.” It prevents him from being “faithful to the earth”—that is, from realizing all his potentialities. God is nothing but the symbol beneath which man’s cowardice and feeble will take shelter, and if so many cherish the myth, they do so merely because it is more convenient not to be than to will to be, because the majority refuse the heroic effort necessary in order to “become what one is.”

It was mainly against Christianity that Nietzsche directed the barb of his criticism: Christianity is the religion that carries the derangement and degradation of man to the furthest possible extreme. It is “an eternal blot upon humanity.” By laying down as principle that “all good, all greatness and all truth are gifts of grace,” Christianity deprives man of the chance to be himself. Christian faith destroys “faith in life.” Christian morality, too, is the direct opposite of all that makes a true man. Supremacy of the simple-minded, of the pure of heart, of the needy, of the failures—is that the true hierarchy of values? In “faith, purity, simplicity, patience, love of the neighbour and resignation” Nietzsche saw “a repudiation of one’s proper Self”; and that is quite correct, except that he interpreted it as an outrage against man. All the sentiments which Christianity recognizes as virtues he regarded as absurd and despicable. “Pity is a squandering, a harmful parasite on moral health. A true man should take as his motto: ‘Be hard.’” Is not that, in practice, the advice followed by great men, the conquerors, the geniuses, who subject events to their own measure—the Caesars and Napoleons? This inevitable conclusion, then, falls from the prophet’s contemptuous lips: “It is not decent to be a Christian.”

It was mainly against Christianity that Nietzsche directed the barb of his criticism: Christianity is the religion that carries the derangement and degradation of man to the furthest possible extreme. It is “an eternal blot upon humanity.” By laying down as principle that “all good, all greatness and all truth are gifts of grace,” Christianity deprives man of the chance to be himself. Christian faith destroys “faith in life.” Christian morality, too, is the direct opposite of all that makes a true man. Supremacy of the simple-minded, of the pure of heart, of the needy, of the failures—is that the true hierarchy of values? In “faith, purity, simplicity, patience, love of the neighbour and resignation” Nietzsche saw “a repudiation of one’s proper Self”; and that is quite correct, except that he interpreted it as an outrage against man. All the sentiments which Christianity recognizes as virtues he regarded as absurd and despicable. “Pity is a squandering, a harmful parasite on moral health. A true man should take as his motto: ‘Be hard.’” Is not that, in practice, the advice followed by great men, the conquerors, the geniuses, who subject events to their own measure—the Caesars and Napoleons? This inevitable conclusion, then, falls from the prophet’s contemptuous lips: “It is not decent to be a Christian.”

For here is the ultimate message Friedrich Nietzsche thought himself called to give the world. A capital event has come to pass, which has escaped the notice of mankind: the day of religions is over; God is dead. The certainty of “the death of God,” which he had received from Heine, is the basis of his message; but not a somehow static certainty, a discovery like that made by historians. The famous words in which he announces this event likewise declare an act of choice. “We are all the murderers of God,” and we continue to murder Him every day. In “deciding against Christianity, not by reasoning but by inclination,” we commit that crime of crimes. “The death of God is not only a terrible fact for man; it is willed by him. Why? Surely, to put an end to his alienation and abasement.” To slay God is to assert man. Nietzschean atheism is not only negative; it claims to offer each one the grandiose adventure of “the difficult and dangerous conquest” of true manhood instead of the cowardly facilities given, as he said, by religion. “Since there is no longer a God, solitude has become intolerable; the superior man must go into action.”

Such is the tone of Friedrich Nietzsche’s atheistic humanism. It acknowledges that the death of God is an event of fearful import, even though the majority of living men are not as yet aware of it. Among those who are, many stand as if stricken with amazement in presence of that murder. “How have we been able to do it? How have we managed to empty the sea?” And they give way to fears which were to be confirmed by historical events: “Shall we not now be continually falling? Shall we not wander in infinite nothingness? Do we not feel the wind of emptiness upon our face? Does it not grow colder and colder, darker and darker?” Prophet of a world swallowed up in night, Nietzsche knew better than anyone that mankind, having murdered God, had entered upon an immense cycle of catastrophe. Unlike the various brands of socialism, he offered no paradise on earth: his “exhilarating science” was devoid of optimism. It is not easy to make a God of man.

What do we find, at last, is the term of that choice? Nothing other than man; not weak and cowardly man wallowing in the mud of religion, but man who truly brought about the death of God and realized all its consequences; man who, like Wagner’s Siegfried, lives human life to the full, without fear of death; man who is conscious of the infinite powers that lift him up and who gives them play; in a word, Superman. It is a Messianic view, but devoid of God, regarding Superman both as saviour and saved. Associated with the “morality of life,” which can be inferred from the invective hurled against Christian morality, Nietzsche’s concept led to the justification of violence, cruelty, the worst inequality of human conditions, and even slavery; for it is right that the race of Superman should be served by the second-rate and cowardly. “It may be,” says Nietzsche, “that all this fills us with terror, but there is something terrible about nature too.” It is “beyond Good and Evil” that man will stand erect, a God wonderful in his perfection, wholly dedicated to the achievement not of virtue nor indeed of pleasure, but of nobility and grandeur.

Such is the atheistic humanism of Friedrich Nietzsche, than whom, it must be said, there has been in our age no more complete embodiment of the satanic rebellion. Aristocratic in the highest degree and accessible to very few minds, Nietzsche’s message went almost totally unheard during his lifetime. That writer whom none read convinced nobody when he assured his neighbours at table: “Forty years from now I shall be famous in Europe.” And yet, without inaugurating a worldwide movement such as that inspired by the thought of Karl Marx, the author of Will to Power and Antichrist was destined to nourish the minds of those who would later believe themselves called to the vocation of supermen. A whole river flowed from Nietzsche, visible in literature. Mussolini and Hitler, those monsters who imposed their tyranny upon millions, were his readers and disciples. Only the concentration camps and gas-chambers could teach humanity the logical significance of Nietzsche’s lyrical aphorisms on the morality of Superman and the crushing of inferior races.

As for the prophet himself, the prophet of abysmal night, he had long been dead, having lived for ten years insane—an existence worse even than death. He had been the most vehement herald of man in rebellion against God; but no one else had given so clear a warning of the risks involved. A Christian cannot speak without emotion of that tragic, that broken witness of the void.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche (1883) by Rudolf Köselitz, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News