We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

While Texas secession would indeed mean that it was no longer one of the states in the union, author T.L. Hulsey has bigger fish to fry than merely separating Texas from California, Minnesota, and New York. What he wants is to start again as the Founders did, but better.

The Constitution of Non-State Government: Field Guide to Texas Secession by T. L. Hulsey (Shotwell, 2022, 260 pages)

“Secession,” writes Robert W. Merry in a recent essay for The American Conservative, “isn’t a word heard in today’s political discourse.” But, he notes, “an extensive poll of 35,307 Americans conducted earlier this year by YouGov, a UK-based market research firm, revealed that some 23 percent of the U.S. population would actually favor the secession of their state from the union.” For Texas Republicans, the figure was actually close to half—44%. Merry takes this as evidence of what many people have been suspecting for a few years: that the United States might be on the brink of large-scale internal violence, perhaps even another civil war.

Are we so different? The so-called Big Sort indicates that we are. Americans of a conservative bent have moved in large numbers to red states and Americans of a liberal bent have been more likely to stay in blue states, changing the make-up of these places considerably. There has been some movement from red to blue, but not nearly in the same numbers. California has lost population in the first census in a century and a half. The effects this will have on the 2024 elections are yet to be seen, but we have already seen many changes in the states themselves. Those of us who moved love our former states, sometimes having a desire to return, but it’s hard not to see them as something of a foreign country on visits back. Besides “the Big Sort,” the other term that keeps popping up is “National Divorce.”

If states on the other side of the Big Sort divide are like a foreign country, might we actually make them such? If we are having a National Divorce, might we sign the papers and move out, politically speaking? While visiting my former state, Minnesota, this summer, I began reading T. L. Hulsey’s The Constitution of Non-State Government: Field Guide to Texas Secession. A politically active and knowledgeable friend who asked about it observed, “We’ve already had the National Divorce; we’re just figuring out how nasty it will be.” One of the 44% of Texans who wants secession, Hulsey’s case is based on his desire that the divorce not be nasty. He wishes that we may have a civil parting and not a civil war. “Secession,” he writes,

is the only peaceful arbiter of intractable political disputes between large societies It seeks not the domination of any existing government, but only to have its citizens go their own way to effect a new government to secure their happiness as they see fit, without a bloody and mutually destructive temporary resolution by force. Those who sincerely want to see an end to the polarization, extremism, and political strife in current society should champion secession, the only peaceful resolution to irreconcilable group differences. Secession is the freedom of association writ large.

Some will find this a heretical notion both generally and in the American context. Secession, they will say, is impossible without war and strife! Hulsey says that this doesn’t match our recent historical record. Do we remember the violent bloodshed when Norway seceded from Sweden (1905)? Iceland from Denmark (1944)? Bangladesh from Pakistan (1971)? The fifteen countries seceding from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s? While war came out of the split-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, all the aforementioned instances were bloodless.

In the American context, though, some will say that secession is something reserved to the Confederacy. Yet, as Hulsey shows in an appendix, there have been secession movements of one sort or another in all fifty of the United States, from making counties independent of states to counties joining other states to seceding from the Union entirely. Up until 1861, Hulsey argues, secession was “the essence of the Jeffersonian federalism that flourished” [his emphasis] in these here United States. He notes that of the “main secessionist impulses” beating before the Civil War, “none of them were in the South” [his emphasis]. Vermont, New York, Connecticut, the Middle Atlantic State, and New England as a whole all had secession movements. Ten years after his own presidency ended, on the jubilee of the U. S. Constitution in 1839, John Quincy Adams spoke on the benefits of the Union dissolving and being brought back together “by the law of political gravitation to the centre.” Though that secession impulse was somewhat quieted after the Civil War and, particularly, in the post-World War II era, this millennium has seen a return of these movements of all kinds, including secession from the Union. Apart from Texas, for instance, red Indiana and blue Hawaii have both nourished secession movements.

Is that legal? Hulsey makes the argument from the text of the Constitution and the understanding of the original thirteen States’ entries into the Union that it is indeed legal. Is it wise? Hulsey agrees that Texas government has been much more prudent than many other states in managing resources and preserving ordered freedom. To protect that from the never-sleeping eye of the ever-growing Leviathan State, he thinks that secession is both necessary and good.

Indeed, you might notice that his title includes the phrase “non-state” government. While Texas secession would indeed mean that it was no longer one of the states in the union, Hulsey has bigger fish to fry than merely separating Texas from California, Minnesota, and New York—sanitizing as that may be. What he wants is to start again as the Founders did, but better.

His “Historical Introduction,” running to p. 43, enters the current argument about whether our country is still under the Constitution of 1789 or not, and concludes that we have not been under it since at least the Civil War. Going back behind the use of the Civil Rights Act to create a de facto and de jure new Constitution (as Christopher Caldwell has argued), and even behind the rise of the Progressive Administrative State and its explosion under the New Deal (as many Claremont Institute thinkers have argued), Hulsey argues that our nation as a Union of States ended effectively with Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus against the Constitutional guarantees and against the Supreme Court’s ruling that it was unconstitutional. The further reduction of the states in the Reconstruction Period marked, for Hulsey, the institution of “a multinational superstate with a completely politicized judiciary.” This may be hard to swallow for many, given the great evils of slavery and racism which pervaded much of southern law and custom. Was it a greater loss to change our way of thinking about the state and national governments than to forcibly change those states and free those slaves?

To most moderns, this is unthinkable. If World War II was the last “good war,” then the Civil War was a quintessentially good war, and the South had to be conquered. To say otherwise is today verboten and, worse, “right wing.” But Hulsey’s case actually provides food for thought about how at least parts of our modern liberal-left might have been right about our history. His case is that the purported solution to the evils present in our country in the South may have been worse than the cure since we now had a supreme “unitary state” that made any real federalism only a shadow of its former self. And unitary states have their own logic. He notes that the next military action engaged in by our now “unitary government” was that of an “aggressive genocidal war” for the “removal of the American aboriginals from its interior.” And the next war was the 1898 Spanish-American War, “not a war in defense of American lives or property, but an unprovoked imperial war.” The Progressivism of Wilson, World War I, the New Deal, the Great Society, the Civil Rights regime, and all the rest might be said to follow from this forsaking of a union of states for a unitary state that sits atop the many different American communities and forces solutions on them.

No, Hulsey wants something different from the modern unitary state. Part one, titled “Apodictic Foundation,” runs (with notes) to page 180 and is actually dedicated to laying out what a non-state constitution would be. This philosophical foundation includes a lot of philosophy that some readers will find hard to follow, while others will think it unnecessary. Hulsey lays out his arguments based on insights from Johannes Althusius, John Locke, Aristotle, Aquinas, and the great Austrian economists, especially. Along the way, he often engages in very biting commentary involving examples of the mess we find ourselves in today, as well as his own theories about how our intellectual history would be different if, for instance, the Pelagian side would have had a better hearing against Augustine. Some of this could have been perhaps saved for a different essay, but I confess to finding his detours interesting and amusing even when I don’t fully agree.

And, while it should have been broken into separate chapters, one can follow his neatly-laid conceptual foundation of a different kind of nation that does not have a “state,” laid out in the first paragraph:

Architectonics is the method that establishes the dominium sortiens: The society of absolute property rights, the absence of public goods, and the sovereignty of the people in community, exercising decision-making not through oligarchic elections but through democratic sortition.

Hulsey is of the older libertarian school. He doesn’t think there is some absolute right to do “gender transition” surgeries on kids or smoke weed, but he does see private ownership in the same light as did Pope Leo XIII: “sacred and inviolable.” He wants an end to the idea of public goods in the modern sense, as the creation of goods by a government that taxes the people’s wealth. That includes courts and policing, which can be set up by local communities. And he wants “we the people” to actually mean something.

Like Chesterton, Hulsey believes that our modern system of voting for representatives is overrated since getting elected seems to involve demonstrating popularity more than talent. His notion of sortition is in service of “the annihilation of politics.” At least politics as we know it. What he wants is an identification of the most competent people in a given community. This is why he wants his system called “kleristocracy,” for it is rule by the able (chosen at random from this pool). (We live, it would often seem, in the opposite: kakistocracy, or rule by the worst.) Sortition is then the random selection of such individuals to fulfill legislative functions. If you think that’s unreasonable, it’s the basis of our jury system—albeit the selection of those capable would be before, rather than after, the lottery as our jury system has it. What legislators would do then is seek not mere majoritarian positions but unanimous agreements (or as close as possible) on policies. And the government would not have to provide

One might say such a system is unrealistic or has bad historical precedents. Yet, as with secession, Hulsey has a great many examples of such systems working in the past. Not only did Athens and the ancient world often practice sortition, but so, too, did other polities. The Hanseatic League existed for five hundred years with arrangements very much like the ones for which Hulsey advocates. The Venetian Republic survived for more than a millennium.

If you think this is all a pipe dream, with big picture and no specifics, part two of the book is “Instantiation.” In it, you can read all about how a new Texas Republic would operate according to Hulsey’s ideas. One can note that the public (or government) school system would be ended. Citizenship would be more difficult to obtain for those with no personal or ancestral history in Texas. And taxes would be minimal without all that government to support.

There is too much detail to cover in a review, but I think one of the key elements is the new division of counties, for it is at the county level that almost all of the needs that were formerly taken up by the state would be accomplished. Hulsey takes seriously the idea that any real political community must have human dimensions. He would divide in two any county that reaches 400 thousand people.

Hulsey’s vision is a radical one, for it wishes to get back to the roots of our modern arrangements. For many, it will be a political bridge too far. But I think even many on the right who wish to defend the original Union are open to thinking about things in a new light. We live in precarious times that demand hard thinking about what we might need to do even if we don’t want to. Only fools don’t make contingency plans.

What Hulsey shows is that political necessity might well be the mother of an invention that actually fits better with the understandings our Founding Fathers had about political reality and the right way to guarantee ordered liberty. The contingency plan may well be better than Plan A and also provide ideas for those who want to keep the Union but make it work better. It also shows that the disputes between libertarians and third-way Distributists and Communitarians are not necessarily absolute. Hulsey thinks market solutions are more often than not better; he also thinks the proper ecosystem for them is a small community with real but truly limited authority existing in a Republic that does not control everything.

Oh, say! Can you secede? If you can, The Constitution of Non-State Government provides a vision that might appeal to E. F. Schumacher as well as Ludwig von Mises and John Quincy Adams. Small, devolved, sortive, and unanimous is beautiful.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

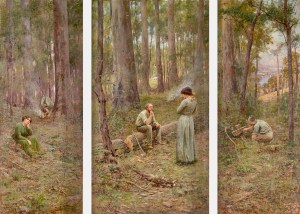

The featured image (detail) is “South Texas Panorama (Mural, Alice, Texas Post Office)” (1939) by Warren Hunter, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News