We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

As Western Civilization has proceeded from “dawn to decadence,” in the words of the great historian, Jacques Barzun, here are five movies that may help viewers ponder what went wrong and what they should do at the “end of all things.”

1. The Mosquito Coast (1986)

Allie Fox (Harrison Ford in one of his best performances) is an eccentric inventor who is disgusted by the crassness of American consumer culture and alarmed by increasing crime and the looming threat of nuclear war. “Look around you: How did America get this way?” he muses to his oldest son, Charlie (River Phoenix), as they drive in their pickup truck down a main street. “Land of promise, land of opportunity. Give us the wretched refuse of your teeming shores. Have a coke. Watch TV. Go on welfare. Get free money. Turn to crime. Crime pays in this country. . . . Buy junk. Sell junk. Eat junk. Why do they keep coming? Why do they put up with it?” As the camera shows a town cluttered with fast-food restaurants, strip malls, gas stations, and advertising signs, Fox says to his son: “Look around you, Charlie. This place is a toilet.”

Fox’s diagnosis of what ails America reflects a strange blend of anti-capitalist and nativist thought. “I don’t want my hard-earned dollars being converted into Yen,” he tells a hardware store clerk who offers him a Japanese-made piece of rubber. “The whole damn country is turning into a dope-taking, door-locking, ulcerated danger zone of rabid scavengers . . . criminal millionaires and moral sneaks. Nobody ever thinks of leaving this country. I do. I think about it every day. I’m the last man.”

In a voiceover, Charlie says:

All winter father had been saying, “There’s going to be a war in America. It’s coming,” he said. He was restless and talkative. He said the signs were everywhere. In the high prices, the bad tempers, the gut worry. In the stupidity and greed of people. Bloody crimes were being committed in the cities, and the criminals were unpunished. It wasn’t going to be an ordinary war, but a war in which no side was entirely innocent.

Fox decides to move his wife (Helen Mirren) and three children to the remote Mosquito Coast of Central America. He idolizes the jungle as a pristine, primitive state where man can live uncorrupted and society made anew. “I’m the last man,” Fox tells Charlie. The Foxes are accompanied on their voyage to Central America by a slick, Bible-quoting Christian preacher (Andre Gregory) whose fundamentalist brand of religion disgusts Fox. The preacher plans to set up a branch of his church on the Mosquito Coast.

Once he has arrived in the jungle, Fox and his vision are slowly corrupted and he becomes a cult leader, like the preacher he despises. The black migrant workers who follow him to Mosquitia even address Fox as “father.” Though Fox idealizes the jungle as a paradise, he sees one flaw with primitive life: a lack of air conditioning. He thus brings with him a design for a giant ice-making machine, which he rigs to provide cool air to the huts in the town he has established. “Ice is civilization,” Fox pronounces.” He labels the contraption “Fat Boy,” a conflation of the nicknames for the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, and like those fearsome creations, the machine becomes first a child to its maker, then a god, and eventually an agent of death.

As his new Eden crumbles around him, Fox descends from eccentricity into madness, turning on everyone who dares to challenge his vision. The story ends in tragedy. At its core, The Mosquito Coast is a powerful commentary on original sin and the dangers of utopianism.

“How did America get this way?”

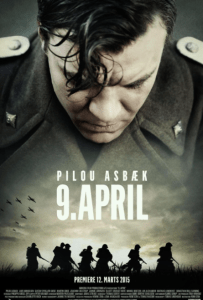

2. April 9th (2015)

How much resistance is a man—and a country—obligated to muster against insurmountable odds? This is the central question of the excellent Danish film, 9.April, which depicts the invasion of Denmark by the Nazis in the spring of 1940. Based on official reports and eyewitness testimony, the film tells the story of a bicycle infantry company charged with offering the initial resistance to the Nazi advance.

The film is permeated by a somber and ominous tone. The question is not whether the Danes will lose, but how long they will fight, and what will happen to the men of the bicycle company. Of course, the Danes are waging war for the purest of purposes: the defense of their homeland. They are fighting for “God, King, and Country,” as a colonel reminds the protagonist, the bicycle unit’s junior officer, Second Lieutenant Sand. “The enemy has breached the border,” another colonel announces. “Denmark is at war. Gentlemen. Now is the time to show what we’re made of.” Here we have beautifully old-fashioned ideas out of vogue in today’s Woke world: the idea that one’s country’s borders are worth fighting for, no matter the odds; that this kind of war makes for a holy cause; and that physical danger is what reveals the true character of men.

I wrote more about April 9th here.

3. Signs (2002)

Director M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs tells the story of a farmer and his family in eastern Pennsylvania who are among the first to experience the onset of an alien invasion of the Earth. Graham Hess (Mel Gibson) is an ex-Episcopal priest who lost his Christian faith after his wife was hit and killed by a truck whose driver fell asleep at the wheel. After the accident, Graham quit the priesthood, turned to farming, and, as the movie begins, is trying his best to raise his two children, Morgan and Bo (Rory Caulkin and Abigail Breslin). Graham’s brother Merrill (Joaquin Phoenix) has moved in with his brother in an effort to comfort him and help with the child-rearing.

Director M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs tells the story of a farmer and his family in eastern Pennsylvania who are among the first to experience the onset of an alien invasion of the Earth. Graham Hess (Mel Gibson) is an ex-Episcopal priest who lost his Christian faith after his wife was hit and killed by a truck whose driver fell asleep at the wheel. After the accident, Graham quit the priesthood, turned to farming, and, as the movie begins, is trying his best to raise his two children, Morgan and Bo (Rory Caulkin and Abigail Breslin). Graham’s brother Merrill (Joaquin Phoenix) has moved in with his brother in an effort to comfort him and help with the child-rearing.

Mysterious events begin to occur on the Hess farm. First a crop circle is found in the cornfield; next, the family dog attempts to attack the Hess children; then someone is seen climbing at night onto the roof of the family’s house. Graham reports the events to the police, and soon it is learned via television news that such strange happenings are taking place around the world. Strange lights appear in the sky, and a frightening creature is captured on video at a kids’ birthday party in Brazil. Graham has two disturbing close encounters of his own with apparent alien beings. The Hess family eventually is forced to barricade themselves in their farmhouse, where they wage a final confrontation with the attacking aliens.

Using a technique that made his earlier film The Sixth Sense a smashing success, director Shyamalan introduces a “payoff,” a shocking revelation that gives new meaning to film’s prior events, at the end of Signs. Here the aliens are defeated by the Hess family through a combination of seemingly meaningless and unrelated earlier events. Graham’s dying wife had told him vaguely to “see” and instructed him to tell Merrill, a former baseball player, to “swing away.” When the Hesses confront the lone remaining alien, Graham recalls his wife’s words and looks up to see one of Merrill’s baseball bats–with which he set a home run record–hanging on the wall. As Merrill begins to club the alien with it, a glass of water falls on the alien’s skin, burning it. Little Bo has a habit of leaving half-finished glasses of water around the house; an annoying routine has suddenly become a crucial survival factor. Too, Morgan’s asthma, a life-threatening condition, now saves his life when the alien sprays poison gas into his face. This series of events seems to answer the central question of the film: Are life’s events random and meaningless, or are our actions fated and our souls the intimate concern of God?

Signs is a masterpiece and can be enjoyed if one simply interprets the film as described above. However, there is an alternative way of looking at the movie, for it can be argued that the creatures that come to Earth are not aliens from another planet… but demons from Hell.

4. Extreme Measures (1996)

A young doctor (Hugh Grant) discovers that a respected older colleague (Gene Hackman) is secretly harvesting the stem cells of homeless men whom he kidnaps from city streets in an effort to cure paralysis and disease in his patients. Though it strains credulity at times—particularly in a scene involving an underground homeless society—Extreme Measures has several gripping moments, culminating in the confrontation between Grant’s and Hackman’s characters. When Hackman attempts to convince Grant to join him in his diabolical work, Grant responds with one of the most powerful defenses of the sanctity of human life ever recorded by Hollywood on film:

A young doctor (Hugh Grant) discovers that a respected older colleague (Gene Hackman) is secretly harvesting the stem cells of homeless men whom he kidnaps from city streets in an effort to cure paralysis and disease in his patients. Though it strains credulity at times—particularly in a scene involving an underground homeless society—Extreme Measures has several gripping moments, culminating in the confrontation between Grant’s and Hackman’s characters. When Hackman attempts to convince Grant to join him in his diabolical work, Grant responds with one of the most powerful defenses of the sanctity of human life ever recorded by Hollywood on film:

Those men upstairs, maybe there isn’t much point to their lives. Maybe they are doing a great thing for the world. Maybe they are heroes. But they didn’t choose to be. You chose for them. You didn’t choose your wife or your granddaughter. You didn’t ask for volunteers. You chose for them. And you can’t do that. Because you’re a doctor, and you took an oath. And you’re not God. So I don’t care if you can do what you say you can. I don’t care if you can cure every disease on the planet. You tortured and murdered those men upstairs. And that makes you a disgrace to your profession. And I hope you go to jail for the rest of your life.

5. Good (2008)

The Devil seeks to unleash great evil on God’s creatures and creation by luring his human victims along, step by step, into committing first several small acts of evil. He finds openings wherever he can, tempting them with worldly things to make little moral compromises. Often it is too late when the victim realizes what hell he hath wrought. This is the story of Good, a film set in 1930s Nazi Germany. John Halder (Viggo Mortensen) is a professor of literature whose novel romanticizing euthanasia brings him favorable attention from Hitler himself. In the course of the movie, Halder abandons his needy wife and deserts his desperate Jewish friend (Jason Isaacs) in an effort to curry favor with the Nazi regime and thus advantage for himself. “I never thought it would come to this,” Halder cries when he finds himself an SS officer in a concentration camp at the film’s end. The Devil’s own rarely think so in the beginning, Professor Halder.

The Devil seeks to unleash great evil on God’s creatures and creation by luring his human victims along, step by step, into committing first several small acts of evil. He finds openings wherever he can, tempting them with worldly things to make little moral compromises. Often it is too late when the victim realizes what hell he hath wrought. This is the story of Good, a film set in 1930s Nazi Germany. John Halder (Viggo Mortensen) is a professor of literature whose novel romanticizing euthanasia brings him favorable attention from Hitler himself. In the course of the movie, Halder abandons his needy wife and deserts his desperate Jewish friend (Jason Isaacs) in an effort to curry favor with the Nazi regime and thus advantage for himself. “I never thought it would come to this,” Halder cries when he finds himself an SS officer in a concentration camp at the film’s end. The Devil’s own rarely think so in the beginning, Professor Halder.

I wrote more about Good here.

This essay was first published here, in a different form, in March 2015.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News