We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Playwright David Lane has graced the Christian community with a formal, blank-verse play that takes up the war of gods and demons. “Dido: The Tragedy of a Woman” retells the tragic tale of the “Aeneid,” but with some dramatic plot twists that allow it to function both as a timeless meditation on the universal issues of natural law, idolatry, and passion gone awry, and a modern commentary on relativism, utilitarianism, and abortion.

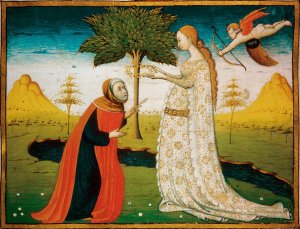

In the opening Book of the Aeneid, Virgil’s reluctant hero washes ashore on the North African city of Carthage. Though Aeneas has been commissioned by the gods to found a new Troy in Italy, a city destined to become the center of a world empire that will bring universal peace and law, he is weary of his journey. The widowed Aeneas soon falls in love with the queen of the newly-founded city of Carthage, the widowed Dido, and forsakes his duty (pietas in Latin) to remain with her.

But the gods have other plans for Aeneas, and so Jupiter sends Mercury to Carthage to order the wayward Trojan to leave at once and resume his voyage to Italy. Though he must leave, the overly stoic Aeneas botches the breakup, and, as his ship sails off, Dido builds a great pyre and immolates herself on it. Before dying, however, she levels a terrifying curse on Aeneas and his descendants. No love, she pledges defiantly, will ever exist between their peoples; rather, when the time is ripe, an avenger will rise up out of her bones to exact vengeance.

For the Romans, that vengeance fell a thousand years later when the Roman Republic went to war with the Carthaginian Empire, and Rome herself was nearly destroyed by Dido’s avenger, Hannibal. But who exactly were the Carthaginians? The answer to that is revealed in the name the Romans gave to the three long wars they fought with Carthage: the Punic Wars. Punis is how the Romans pronounced Phoenicia (there is no “ph” in Latin, which is why they called the land of the Philistines, Palestine), the old foes of Israel whose capital cities were at Tyre and Sidon in the land we now call Lebanon. Carthage was the African outpost of Phoenicia’s trading empire.

In the end, Rome defeated and utterly destroyed Carthage (146 BC), but she never forgot how close she had come to being destroyed herself by Hannibal in the closing decade of the third century BC. Fast forward to the early decades of the twentieth century, when a British essayist, poet, novelist, critic, and Christian apologist named G.K. Chesterton decided to take a second look at the Punic Wars from the perspective of divine providence. In Part I, Chapter VII of The Everlasting Man (which bears the title “The War of the Gods and Demons”), Chesterton argues that in the Punic Wars, we witness nothing less than an epic battle between the good pagans (Rome) and the bad pagans (Carthage).

God had commissioned his Chosen People to wipe out the Phoenicians, but they had failed their commission. Why did God call for the destruction of Phoenicia? Because they practiced one of the worst sacrileges of the ancient world: sacrificing children to the demonic Baal (AKA Moloch). So corrupting was the influence of Phoenicia that the Jews themselves, in hopes of appeasing Baal, passed their own children through the fire. Ahab was corrupted by his Phoenician queen, Jezebel, and it was against her priests of Baal that Elijah held his great showdown at Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18). Nine hundred years later, Jesus would rebuke the unbelief of the Galilean Jews by accusing them of being more faithless than the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorra, Tyre and Sidon (Luke 10)!

Such was Phoenicia, but the Jews proved unable, and unwilling, to end the bloody reign of Baal. As a result, Chesterton argues, God raised up the best and noblest of the pagan nations, Rome, to finish what Israel had started. Nearly every student to whom I have taught the Aeneid has recognized the name Hannibal, but none has ever made the connection that I myself did not make until I read The Everlasting Man: namely, that Hannibal means “the grace of Baal.” Though Hannibal should have destroyed Rome, the pietas-loving Romans rose up out of the ashes of defeat to conquer the Baal worshippers once and for all.

Chesterton published The Everlasting Man in 1925. Almost a century later, in 2016, playwright David Lane graced the Christian community with a formal, blank-verse play in the manner of Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Racine—not to mention Milton’s Samson Agonistes and Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral—that takes up again the war of gods and demons. Now available, with a new glossary, in a second edition (2019), Dido: The Tragedy of a Woman retells the tragic tale of Aeneid IV, but with some dramatic plot twists that allow it to function both as a timeless meditation on the universal issues of natural law, idolatry, and passion gone awry, and a modern commentary on relativism, utilitarianism, and abortion.

David Lane, a retired editor and Vietnam War veteran who has long served as the Chairman of Una Voce New York, an organization dedicated to restoring traditional Roman Catholicism, especially the ancient Latin Rite, is the author of The Tragedy of King Lewis the Sixteenth: another blank verse play dedicated to restoring a gravitas to poetic drama that has been lost over the years. If, in King Lewis, Mr. Lane exposed the dangers of a revolutionary ethos that would throw out tradition, hierarchy, and revealed religion (a danger to which the Catholic Church was sadly afforded a front row seat when the Jacobins began guillotining priests and nuns), in Dido, he exposes the dangers of abandoning natural law to embrace what John Paul II called “the culture of death.”

While following the basic outline of Aeneid IV, the play gives Dido and Aeneas an infant boy named Chryses—the same name as the priest who, in Iliad I, prays to Apollo to send a plague on the Greek camp for the sacrilege committed against him and his daughter by Agamemnon. Mr. Lane also adds a corrupt priest of Moloch named Adonibaal (the generic Hebrew word for God, Adonai, linked syncretistically to Baal) and his nephew Bodphoebus, who, due to the influence of Aeneas, has turned his allegiance away from the demonic Baal/Moloch to the more civilized Greco-Roman Apollo (one of whose titles is Phoebus).

After Mercury orders Aeneas to leave Carthage, Adonibaal, who despises the Greco-Roman religion of Aeneas, with its allegiance to a fixed code of natural law, tries to draw Dido back into the dark, heathen religion of Phoenicia by convincing her that she can coax Moloch into returning Aeneas to her if she will only sacrifice Chryses. With the help of Anna, Dido’s relativistic-minded sister, Adonibaal slowly whittles away at Dido’s sense of the natural law. At the thematic core of the play lie three interchanges between Adonibaal and Bodphoebus, Adonibaal and Dido, and Dido and Anna that recall the debate between Creon and Antigone, in Sophocles’ Antigone, over the existence of a higher law of piety that transcends the man-made laws of the state.

Thus, when Adonibaal tries to reduce the natural law of the virtuous Aeneas to a product of secular power politics (“What shall this ‘Law’ / Aeneas crowns be aught but one man’s truth / On other men imposed.”), Bodphoebus counters that the natural law is not invented, but recognized in the conscience (“Sure, on the tables of the human heart, / That Law, ‘tis clear, is past regret inscribed. / Aeneas dared no form to will, my lord, / Nor made to wave it real with wizard’s wand; / He did but Nature humbly recognise.”).

Later, speaking as if he were a dark pagan forerunner of Planned Parenthood, Adonibaal assures the abandoned, emotionally distraught Dido that her absent lover will be delighted and fall into her arms again if she will only “abort” their love child on the utilitarian altar of Moloch. Dido knows he speaks falsely and expresses her disgust for “the blating monster god / Of terrors hideous: Moloch, smeared with deeds / Of blackest hue.” No, she will not return to this death cult, “which Lord / Aeneas, citing universal say / Of conscience, prayed Our sovranty to put / At once unto the everlasting ban.”

In the next scene, the play becomes positively chilling as Anna tries to blunt Dido’s sense of right and wrong by slowly dehumanizing Chryses into a “pretty puppet,” a “cub unlicked,” a creeping bug, and, finally, a “little coin.” She even promises Dido that the baby won’t feel any pain when it is thrown into the fire! She presents the child as a means of exchange by which Dido can purchase Aeneas’s love. Dido boldly resists—until she realizes that she can evade Aeneas’ moral anger when he learns she killed their child by tricking him into believing that she gave him up for adoption. Thus does the sin of murder naturally give way to the sin of bearing false witness.

In the end, Dido is about to sacrifice Chryses when Aeneas, who had decided on his own to return and take Dido and the boy with him to Italy, arrives in time to save his son. Dido gives a full confession, and Aeneas takes Chryses with him, leaving Dido behind to carry out the work of civilizing the Carthaginians. Sadly, Dido is so stricken with guilt that she burns herself on the pyre after Aeneas’s ship leaves.

The play, however, leaves us with a glimmer of hope. Aeneas’s companion, Nisus, first assures us that man can avoid the madness of Adonibaal’s black magic by using the tools “of sober reason and / A fund of hard experience and light / As Heaven throws,” and then offers a pagan prophecy (a la Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue) of Christ: “One morn, meseems, / A birth of Light will be that every mist / Of mind and heart shall vapour off.”

Dido: The Tragedy of a Woman is a timely and thought-provoking play written in a blank verse that is both strong and supple. Still, I suspect that many readers will be put off by its heavy use of unfamiliar and archaic words. I must admit that I often found the diction to be a bit stilted, distracting from the flow of the verse. But then, to be honest, I am a Romanticist who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Wordsworth’s Prelude, and am thus temperamentally allergic to eighteenth-century poetic diction.

But this reservation is a minor one. I strongly applaud Mr. Lane for attempting, and mostly succeeding, at raising the poetic bar and seeking after a level of verse that touches on the sacramental. Indeed, though I am a Protestant, I further applaud Mr. Lane for working hard to restore the verbal dignity of the Mass and to resist the over-familiarizing of sacred, liturgical language. Not only the Catholic Church, but the full Body of Christ needs more warriors like David Lane.

Onward Christian playwright!

This essay was first published here in February 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Dido” (1781) by Henry Fuseli and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News