We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

“The Chosen” is one of the few examples of television that really serves a higher purpose. Far beyond “entertainment,” it can enhance our traversal of Jesus’ life through liturgy and prayer.

“We expect from TV consequences of the greatest importance for an increasingly dazzling exposition of the Truth.” [1] —Pope Pius XII (first televised Easter address, 1949)

From its beginnings in the mid-20th century, television has held great promise as a medium for art, entertainment, and uplift. This promise has only been sporadically fulfilled, it is true, and unfortunately much of the time TV (especially when driven by ratings and commercialism) has remained a generator of the tawdry and the ephemeral. But with the right talent in place, and the right priorities and artistic and moral values, television retains strong possibilities.

The strength of that possibility lies in fictional television’s ability to create an imaginative world that is conveyed into our very homes, to enter our consciousness and become part of our lives in a more intimate way than is possible with a theatrical film. When the television program is a series, with multiple episodes carrying common characters and themes over one or multiple seasons, this life-enhancing aspect of TV is deepened. We grow along with the characters, become involved in their lives almost as if they were real persons, and await breathlessly further developments in the plot. The power of television, at its best, is to touch millions of lives while conveying a set of ideals and values, and in doing so draw people (including families) together.

Fiction shows of the early days of TV presented imaginative stories with a moral vision based on everyday life. Recall the classic domestic comedies of the 1950s and ‘60s such as Leave It to Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show, and Father Knows Best, or the many popular westerns. Dramatic shows like The Twilight Zone presented moral parables in fantasy form. And everywhere behavior was portrayed for moral example, especially (but not exclusively) for young viewers. Think of how the family interactions of the Cleavers or the Andersons set an example for how people ought to behave as members of civilized society, or how the citizens of Mayberry imaged a sense of community life. Shows that were daring could (pending the approval of sponsors) tackle social issues in a subtle, intelligent, and thought-provoking way.

The makers of the contemporary series The Chosen have tapped into this honorable televisual tradition in a big way—the biggest way possible, since the story they have elected to tell is no less than the foundational narrative of our civilization, the gospels—the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Chosen is a Web-based dramatic series, rather than a program on network television. All the same, it makes perfect sense to view it as part of the tradition of series television. Fans of the program refer to it as a television show, and it functions much like TV series of the past, regardless of how we watch it (the episodes have been available online for viewing free of charge since the series’ inception five years ago). At the same time, the show’s independence from the commercial television world has allowed it to remain true to the artistic and spiritual vision of its creators.

The Chosen recently passed the midpoint of its projected arc, its fourth season (with each “season” consisting of a series of eight episodes). Directed by the Evangelical Christian filmmaker Dallas Jenkins, the series stars the Catholic actor Jonathan Roumie as Jesus. The Chosen has been a wild, unexpected success. It has been seen by millions of people worldwide and translated or dubbed into scores of languages. More than merely a television series, The Chosen has proven to be an artistic, spiritual, and cultural phenomenon of the highest importance.

In the first place, in treating the life of Jesus as a television serial, the makers of The Chosen have had a brilliant inspiration. As we know, believers are called to follow their Lord; through a serial television program, we can now “follow” him through a series of episodes in which the various events of his life are dramatized with an attempt to recapture their original immediacy and color. This kind of serialization of the gospel is already familiar to us from the cycle of readings used in the liturgy. Now we are given a new, televisual, way to “follow” the life of Jesus, one that can be entirely complementary to our spiritual life.

Yet, as the makers of The Chosen have repeatedly insisted, the program is in no way meant as a replacement for the gospels but rather, as an envisionment of the gospels, a new work of art that points to the gospels and helps us re-engage with them. Taking the gospel texts as a basis, the Chosen creators have provided a kind of “enfleshment” of the sacred text that is quite unlike any other biblical film I have seen. In doing so, they are enriching the Christian imagination like all the great artists of the past.

One of the reasons for surprise at the series’ success has been its unconventional source of funding. From the start, the series has sustained itself through crowdfunding, an online platform for raising money. Patrons have donated money out of a belief in the project’s importance of the project and a desire to see more Christian cinema. As a result of the unique funding method, interaction with the public has been key to the series’ operation (about which more later).

With the completion of the fourth season (ending with Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on the eve of Holy Week) The Chosen has reached an artistic pinnacle. The time has come to take stock of this remarkable series and the equally remarkable devotion that has grown up around it.

First, a personal note. I first dipped my toes into the waters of The Chosen a couple of years ago. Sampling the first episode of the first season, I was not strongly impressed. A lot of screen time was taken up with subsidiary characters and events, with Jesus not appearing until the end of the episode; I was not prepared for the “slow burn” style of storytelling or its popular touches. I decided that this particular faith-based production was not for me and did not continue watching. There matters lay until this spring when, after reading about the upcoming release of the fourth season, I decided to give the series a second try. This time my impression was the complete opposite of my initial one: I was hooked, and soon became caught up with the entire series. The Chosen seemed to me a work of genius and one of the most compelling dramas (biblical or otherwise) I had ever seen.

Let us start with the show’s title. A series about the life of Christ could be called many things: “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” “Jesus of Nazareth,” “King of Kings.” Why “The Chosen”? It takes only a little thought to realize the title’s triple meaning: the Jews as the Chosen People of God; Jesus as the Chosen One (the Messiah); and the disciples as the ones chosen to spread the Gospel to the world.

This multilayered approach is emblematic of the series as a whole. The Chosen is written by theologically serious Christians who know how to shape a story into a convincing arc according to the best traditions of cinematic storytelling. Scripture itself is storytelling of a high order; yet the Chosen writers have reacted to the often sparse nature of the scriptural narrative—the evangelists were writing histories, after all, not novels—to bring the characters and situations to more vivid life. Taking clues and inferences from the gospel text, they create compelling and entirely plausible character arcs for the biblical dramatis personae that illuminate the situations and connect with us, the audience. All of this is carried out with a deep respect for scripture, history, culture, and religious traditions—particularly Jewish tradition and ritual, which are highlighted throughout the program. A clerical board consisting of a Messianic Jewish rabbi, a Catholic priest, and an Evangelical professor serves as theological advisors on the show. Because of the broad framework (seven seasons) they have allowed themselves, the creators are able to go deeply into the cultural and historical background of the gospels as never before. While remaining faithful to scripture, the writers combine incidents in a format that brings out meaningful new patterns and themes. It is as if they have created a new work of art built upon the gospels and pointing back to them as source and summit.

How have the writers “fleshed out” the narrative? The examples are countless, but let me point to a few. At the beginning of their association, Simon Peter begged Jesus to “Depart from me, for I am a sinful man.” The Chosen writers have taken their cue from this statement to construct a subplot in which Simon Peter is behind in his tax payments (to St. Matthew, no less) and making underhanded deals with the Romans in order to catch up on his debts. Or again, the writers have invented a major plot point as a setup to St. Thomas post-Resurrection doubts (no spoilers here). The viewer is given a credible throughline to events, making the story more organic and thus resonant. As someone who writes screenplays himself, I can tell you that such character and story arcs are what screenwriters continually try to achieve, and it is no different when one is working on the basis of the Gospel.

I realize that such extra-biblical embellishments will be controversial with some. Yet time and again I have found that whenever a particular writing choice, plot element, or character portrayal on The Chosen seems questionable or far-fetched, if you give it time it eventually makes sense, forms a meaningful pattern. You may not agree with everything the show’s creators do, but you eventually come to see why they did it. The Chosen is here for the long haul, and I encourage anyone starting out with the series to stick with it. The writers are working a providential plan with their scripts, one unfolding over a long span. And on the subject of speculative additions, let’s recall St. John’s words: “there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself would not contain the books that would be written.”

Another hallmark of the writing on The Chosen is that, although the settings are authentically first century (all achieved in an expansive plot of land in Texas, no less) the dialogue is shot through with contemporary lingo. Characters pepper their conversation with “OK” and use phrases like “Save that thought” and “Not too shabby!” Jesus’ memorable “Get used to different” and “I make people what they aren’t” are among the show’s emblematic phrases. These deliberate anachronisms are also an essential strategy in Jenkins and company’s plan. For they are pulling out all the stops to bring the gospels front and center in our lives, and that entails a departure from the reverential, classicistic style in which the biblical events have often been dramatized in the past.

I suppose some will object to this style of presentation. But we must understand that the Chosen creators are not going for a theatrical, hagiographic presentation of the Bible but a naturalistic one, stressing “relatability” (a buzzword, perhaps, but still a valid concept). The result is that the incarnational dimension of the story is constantly emphasized. In The Chosen we see living human beings, not statues or icons. The closest artistic analogy would be with a Caravaggio canvas, full of earthy detail. A Catholic priest has compared the series to the medieval mystery plays, which often embellished or “modernized” elements of the Bible.

Yet the anachronisms and modernisms on The Chosen never seem cheap or tasteless. Instead, they show a rich imaginative invention. How is this achieved? I think the use of accents in the show accounts for it in large part. That Jesus and his disciples speak with Middle Eastern accents provides a layer of distance and otherness that tempers the popular tone in the dialogue. We, the audience, have to believe we are hearing the equivalent of those expressions in colloquial Aramaic, relayed to us in modern English, if that makes sense. The Roman characters, meanwhile (who are also richly characterized) speak with American or British accents, sounding “foreign” in a different way. By differentiating the two groups by looks and accent, The Chosen emphasizes the social, ethnic, and religious tensions between them that escalate, leading steadily and inexorably to the crisis of the Cross.

Yet by no means does The Chosen present us with a constant drumbeat of doom. The series’ emphasis on the human dimension of the Gospel manifests itself in a pervasive use of humor, most of it of a quiet nature; at its best, the humor is used to illuminate theological truths as well as to provide leaven for the serious business of the story. The classic traditions of the situation comedy come into play here (who would have thought?) and we are reminded that, as Chesterton memorably put it, that which is comic is also cosmic.

Even aside from its artistic value, The Chosen makes for excellent instruction; the episodes often have the effect of clarifying certain points about the gospels, pointing up the connections between persons and events. Let us be honest: are all of the apostles clearly demarcated in our minds? The Chosen puts a face to each and gives each a distinctive personality and quirks. The interaction between the disciples is one of the main focal points of the series, dramatizing the tensions in the nascent Church that are still present today. The treatment of St. Matthew has drawn much attention and empathy from audiences. The tax collector is here an awkward young man whose sense of isolation from other people led him to abandon his Jewish heritage and do work for the Romans. The disciples’ foibles and imperfections become reflections of all of us, their spiritual descendants, who strive to follow Christ today.

Indeed, the writers’ passion for presenting the gospels on a “relatable” basis has led them to put a charmingly contemporary spin on certain characters and plot elements. Matthew’s accent and mannerisms cause the character to resemble countless studious, math-adept Middle Eastern kids we’ve seen in real life. As presented in the series, the politicking, cliques, and jockeying for power among the members of the Sanhedrin are like similar phenomena today.

But while a contemporary resonance is sought, the main aim of the series is to point us back to the gospels, back to scripture in general. Time and again the writers come up with inventive ways to have the characters enact the gospel maxims, thus making the gospel concrete for us and in the process fulfilling the “moral exemplar” role that television played in its golden age.

Director Jenkins has assembled a young, Mediterranean group of actors to portray the disciples who perfectly delineate this motley crew of flawed human beings striving for holiness. Particularly unforgettable are Elizabeth Tabish’s serene Mary Magdalene and Shahar Isaac’s aggressive, muscular Simon Peter. But in fact, each and every one of the portrayals is remarkable. The attention to ethnic authenticity (many of the actors are of Levantine heritage) is a distinguishing and novel feature of the series. In place of the graybeards often pictured in art, we are reminded that the apostles were young men when they walked with Jesus. The scripts also emphasize the inclusion of women in Jesus’ entourage (the “many women” who “followed Jesus from Galilee”), with the addition of a lady from Ethiopia serving to symbolize Jesus’ appeal to all nations and races.

Each Chosen episode is a rich mosaic of incidents from the gospels, put together with integration and insight by the writing team of Ryan Swanson, Tyler Thompson, and Jenkins. Often an episode is framed by an introductory “flashback” drawn from Old Testament history or from Jesus’ infancy, which throws light on the main action by evoking a parallel or a prophesy that will be fulfilled. And many of the episodes work toward a climax in the form of a monumental set piece (the Sermon on the Mount, the raising of Lazarus, etc.) that propels Jesus further toward the consummation of his mission. Indeed, the viewer is left with no doubt that the Passion is central to the narrative of The Chosen. As Jesus becomes more daring in his healings and preaching of the Kingdom of God, the story careens ever closer toward what seems to the disciples like fatal disaster. Little by little, with great difficulty, they realize that Jesus has come to earth precisely to suffer and die, and not to set up a political government in which Israel will achieve earthly “glory.” The various signs and wonders appear as preludes to Jesus’ true glorification through his Passion and death…and all that follows. How they come to terms with this strange reality makes for much of the drama of the show.

This leads us to what I see as the main weakness of The Chosen. Because the writers committed themselves to a broad framework (seven seasons) and a slow and steady build of the narrative arc, there is much time to fill on a moment-to-moment basis. They have also chosen to structure their scripts to some extent on the modern soap-opera style of storytelling, in which each short scene needs a sort of mini-crisis to propel the story along. What this means is that often, to sustain interest, the scripts resort to sustaining a kind of low-level tension by having characters (mostly the apostles) engaging in petty bickering and minor disputes. Fortunately, by the fourth season the bickering seems to be lessening as the disciples mature more fully into the saints they eventually became, under Jesus’ guidance.

And all such complaints dissolve whenever the series presents us with another scene of breathtaking power, grace, and beauty—of which there is at least one per episode. I know I am not alone when I say that The Chosen routinely moves me to tears, particularly in scenes of healing or forgiveness, but not only. Such moments remind us constantly of how humanistic, how emotionally rich Christianity is. Yet the focus on intimate, touching moments is balanced against the big public scenes, oftentimes serving as climaxes to an episode or a season. The long-range planning on the part of the Chosen writers is evidence of a powerful intelligence at work, and it enhances the experience of those of us who are following the series episode by episode.

The Chosen is anchored by the performance of Jonathan Roumie as Jesus. To call Mr. Roumie’s performance “tremendous” would be an understatement. Here we have Christ in both his warmly human and his authoritatively divine aspects, seamlessly combined. One really can’t overstate what Mr. Roumie has achieved here. To depict Jesus in a frozen piece of visual art (painting or sculpture) is a fine thing. But to animate the statue, to give it life and sinew in space and time and a particular accent and cadence, this Mr. Roumie has done, and it is nothing short of magnificent.

Let me state this without any fear of hyperbole: when you watch Jonathan Roumie, you feel in your bones that this must be what Our Lord was like. The combination of gentleness, courtesy, and virility in Mr. Roumie’s portrayal make us understand at last why these men and women abandoned everything and followed this rabbi. Last but not least, everything we know leads us to believe that Mr. Roumie’s performance comes out of a sense of vocation and a living personal faith.

Christians believe that Jesus is the icon, the true image, of God. In portraying Jesus on film, in a continuing serial, Jonathan Roumie the actor has become an icon of Jesus in a singular way. And his actions and presence in The Chosen, which literally model Christ, in turn influence us to be more Christ-like. Thus, the transformative power of television is realized in the most spiritual way imaginable.

I realize that the very power and popularity The Chosen will pose a problem for some prospective viewers. There is a fear that the portrayals of the show will somehow get in the way of the Gospel for us—as if from now we will see in our mind an image of Paras Patel whenever we think of St. Matthew. Now, consider: do we avoid looking at the paintings of Botticelli and Raphael because they incarnate specific visual ideas of Christ and the other biblical personages? Let us not to be afraid of the image. Ultimately, The Chosen is one interpretation of the Gospel, and as such it can only enhance our Christian imagination, not detract from it.

As mentioned earlier, the connection between Jesus’ humanity and divinity is central to Mr. Roumie’s portrayal. Jenkins and crew have even daringly allowed their film camera into the secret places of Jesus’ inner life, showing the “God goggles” (as Jenkins likes to put it) that imbued the Son of God with divine insight. We see Jesus often very humanly frustrated that the disciples do not understand the nature of his kingdom and mission, despite his careful and deliberate explanation. Some of the most affecting and tender scenes have been those in which Jesus unburdens himself of his sorrow to his Blessed Mother. Mary plays a prominent role in the show as a sort of den mother for the apostles as well as Jesus’ own beloved imma (Mom) who has accepted the burden of suffering with him.

We are reminded that in his humanity Jesus could get tired or frustrated, that healing thousands of people was physically exhausting, and that at the end of it all Jesus needed to escape into seclusion to commune with the Father in prayer. The Chosen takes us into the heart of Jesus’ humanity, yet never is his divine nature and mission ever in question; he continually challenges his disciples in their assumptions and behavior, yet often working in a more subtle and indirect way than they would wish. As a human being, the Jesus of The Chosen struggles to convey to people the divine message of redemption through transcendence that is beyond their present ability to comprehend or accept. All they can do is continue to follow him—bolstered by Simon Peter’s unshakable declaration of faith—no matter what lies ahead, and in the face of developments that seem to cast the whole mission into shadow and doubt.

Jesus’ chief antagonists, the Pharisees, are just as finely and complexly portrayed in the show. They are never mere villains, but rather individuals trying to keep God’s law but blinded as to God’s broader purposes in their midst. The scenes depicting the Pharisees’ arguments and machinations are filled with a rich vein of satire, as well as being historically instructive, helping us understand more fully the opposition Our Lord faced. The writers even succeed in humanizing Judas Iscariot, portraying him as a confused young man with initially good intentions who goes astray because of an inability to lay aside his worldly-minded thinking. The intrigue of the Pharisees and religious leaders lends the narrative drive and excitement, revealing the gospel as the ultimate tale of adventure, suspense, danger, and (divine) mystery.

Details of costume, of architecture, even of cuisine (all the olive oil, honey, fruits, and flatbreads!) all combine to bring Jesus’ world to vivid life for us. The importance given to the material and sensory world helps make The Chosen truly incarnational, just as the probing of motivations and backstories and human interaction succeeds in conveying the gospel in three dimensions.

There are also wonderful moments of reflection, when the narrative stops and we have a kind of theological tone poem. I think of a beautiful sequence in the most recent season, when Mary Madgalene meditates aloud on why God had to choose the way of suffering (“the bitter with the sweet”) to redeem mankind instead of producing the immediate “fix” that everyone had been seeking. In these moments the pure magic of cinema is made to communicate the truth of the gospel in the way it does best: through a symphony of images, words, and music.

Presenting the Gospel in the format of a popular television series is one of the most brilliant evangelizing gambits of all time. And evangelism in the form of outreach and activity beyond the show has been key to the show’s success. This outreach takes the form of simulcasts, commentaries, interviews, Bible roundtables featuring the three-clergy team, and “aftershows” in which we get to see the actors out of costume talking about playing their roles. There are panels in which such questions as “Are you Martha or Mary?” are discussed, bringing the Gospel into our personal lives, and Dallas Jenkins himself may drop by to explain some difficult theological points or writerly decisions in the show. Thus, the show’s creators have made themselves available to the viewing public and stimulated further conversation and reflection outside of the show itself.

In return, testimonials of fans have poured in bearing witness to the transformative effects of The Chosen. People are seeing aspects of themselves in the characters, showing one aspect of television at its transformative best. Outright conversions have come about from the show, and they will no doubt continue as more people come to understand, thanks to the affecting portrayals, why following Jesus is so important. And in addition to its evangelizing force, the show is bringing Christians together, just as the classic works of C. S. Lewis did. I mention these things because it seems to me that such an interactive phenomenon is quite unlike anything else in the history of culture.

When completed, The Chosen will be the most significant cinematic treatment of the life of Christ ever made. It looks as if the fifth season will cover Jesus’ trial, and the sixth will be a slow and richly drawn via dolorosa. And the seventh, we have every reason to expect, will all be about the glorious Resurrection appearances. To be sure, a great part of the excitement of The Chosen has been the opportunity to see the familiar story unfold over time. This concentrates our attention on the aesthetic aspects of the show. The pleasure consists of seeing how the creators will realize various scenes and characters which we have carried in our minds all our lives. Will Gaius, the sympathetic Roman legionary, turn out to be the centurion whose servant Jesus heals (“Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof”)? Will Yusif, the Pharisee who is increasingly open to Jesus’ teaching, end up as Joseph of Arimathea? These questions lend the series a frisson of excitement and remind us that this is all unfolding right now. The Chosen is one of the few examples of television that really serves a higher purpose. Far beyond “entertainment” (the word seems almost like a sacrilege in this context), it can enhance our traversal of Jesus’ life through liturgy and prayer. I believe it is already bringing people closer to Christ and will continue to do so.

*

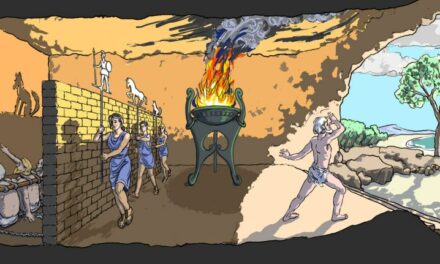

Drama as we know it today, let us not forget, was an invention of the Church and was a means of spreading the gospel message. It started with mystery and miracle plays in the Middle Ages, at first performed within the four walls of the church and eventually moving out into the town square, where long and complex productions about the life of Christ were staged. The advent of film at the turn of the 20th century created a new, astounding way to tell stories visually, and the marriage of religion and film produced many inspirational works. Television brought drama right into people’s homes, thus creating a more intimate form of storytelling.

Ironically, with a superabundance of media, we end up with a world devoid of common cultural touchstones. The Chosen is providing us with such a touchstone, and it is doing it through the modern media itself. It is directing us back—through art and visuals, through language, through thespian skill, through theological and psychological insight—to the ultimate and original touchstone of the Word of God. As Fr. Dwight Longenecker has written, “the film experience is the most fully ‘incarnational’ of all the art forms,” and there’s no reason why that shouldn’t include the “small screen” as well. In The Chosen, the true artistic and spiritual worth of television is being amazingly fulfilled. Just watch.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Note:

[1] Quoted at aleteia.org.

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News