We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

The Benedictine Rule was written in the sixth century, but it is timeless in its appeal. Stability means we find God and happiness right where we are, and that we don’t have to flit about after every trend, fashion or new idea.

In the summer of 1987 I had three months free, and decided to make a hitch-hiking pilgrimage to Jerusalem. I had visited Benedictine monasteries in England and decided to stay in monasteries and convents all along the route. It was a glorious summer and I had an excellent adventure.

In the summer of 1987 I had three months free, and decided to make a hitch-hiking pilgrimage to Jerusalem. I had visited Benedictine monasteries in England and decided to stay in monasteries and convents all along the route. It was a glorious summer and I had an excellent adventure.

One of the best parts of the trip was visiting Benedictine houses all across France and Italy. I stayed at famous places like Mont St. Michel, Solemses and Fleury where the relics of St. Benedict are preserved. I visited Subiaco and Monte Cassino where St Benedict lived and worked. I also stopped at more out of the way monasteries. They were high in the Alps, on an island at Venice, in the centre of Rome and by the Sea of Galilee.

At each monastery I was given a warm welcome in the true Benedictine tradition of hospitality. As I stayed with the monks I got firsthand experience of their simple, balanced, and dignified lifestyle. Many people regard monks as extremists, but I learned to see things in a different way. Here was a group of men who decided to live together to pursue a life of prayer, study, and work. They were not the ones who were insane. Instead their quiet sanity made the usual race for money and power seem crazed and crazy.

St. Benedict is celebrated as not only the father of Western monasticism, but because he is patron of Europe and thus the Father of Western Civilisation. Benedict is patron of Europe because his monasteries helped to preserve the ancient Greek and Roman culture after the empire crumbled. Benedict’s disciples founded monasteries that became centers of classical learning throughout the Middle Ages. The monasteries also became the hubs of health care, justice and the arts. Benedict’s rule fostered a primitive form of democracy in an age of tyranny. The rule also established the foundation for a modern understanding of human rights because in the community each person was treated with intrinsic respect and honour. Benedict’s monasteries promoted hard work, gracious manners, self-discipline, and self-respect. The monks taught that these ordinary virtues were part of the call to holiness. Benedict’s civilized communities remind us that personal virtue is vital for a civilisation of decency, order, and peaceful prosperity.

Benedict lived in the sixth century when the Roman Empire was falling into ruins. Our own society is suffering from the same symptoms of decay as ancient Rome. As late Roman type lawlessness, immorality, greed and despair are all around us, so the simple virtues Benedict nurtured are necessary for our time. Benedict’s principles for a good and balanced life are enshrined in the three vows which Benedictine monks and nuns make. From the three vows of stability, obedience and conversion of life come the balance which we need as individuals, families and as a society.

Stability means being rooted. The Benedictine monk or nun promises to stay committed to his or her monastic community for life. We need this kind of commitment in our marriages and in our communities. To often people are not willing to persevere. When things get rough people bail. Commitment seems to be a dirty word. Stability means getting stuck in and not giving up on a particular community or commitment. Stability means we find God and happiness right where we are, and that we don’t have to flit about after every trend, fashion or new idea.

Obedience is a harsh word in a society where individualism rules and the pursuit of pleasure seems to be the only guiding principle. However, the root of the word “obey” means “to listen.” True obedience means listening to others with patience and a deep level of understanding. The obedient person is always alert to the spoken and unspoken needs of those around them. Obedience builds peace and understanding in communities. Obedience is vital for the virtuous life to prosper. It is absolutely vital for the spiritual life to prosper. A Christian needs to listen to God, listen to the Scriptures, listen to the Church and listen to the Holy Spirit within us. Then, after listening, comes action.

Conversion of Life is the dynamic vow. The person who seeks conversion of life is always looking for a new way to experience life. This principle does not just mean being converted in the religious sense. It is a way of looking at life that is creative, optimistic, and positive. It sees possibilities, not problems. It gives people the benefit of the doubt. It is always seeking to convert the difficulties of life into opportunities for growth. The person who vows to follow conversion of life wants not only religious conversion. He wants to be totally converted as a person and then to convert the whole world from death and despair to new life and hope.

These three principles are not just for monks and nuns. They can be applied to our families, our businesses, our schools, parishes and local communities. The Benedictine Rule was written in the sixth century, but it is timeless in its appeal. It is always relevant because Benedict understood people. Writers on the Benedictine way of spirituality have used his homely rule for life in a sixth century monastery to influence their approach to education, business, politics and the home.

In the 1950s, T.S. Eliot thought that Europe would have to go through a new Dark Age. He also thought that the monasteries would preserve the best of the ancient culture and hand it on to future generations. It may be that as the darkness deepens small core communities will gather to preserve a timeless way of life—a quotidian cycle of work, prayer, and study which circles around everlasting values, timeless truths, and a glimpse of eternal beauty.

This essay first appeared here in April 2014.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

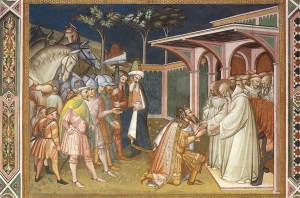

The featured image is “Totila e San Benedetto” (between 1400 and 1410) by Spinello Aretino, San Miniato al Monte, Firenze, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News