We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

As we celebrate the documents produced by the generation that also gave us Paul Revere, let us remember that they knew something that we have largely forgotten: the richness of community life that lay behind those documents, and without which they would never have been written.

We celebrate this weekend a common declaration of independence, the independence of our ancestors from the most far-flung empire in history (unless one considers ours, today); we wave flags and go to parades, most of which, at least in the small towns, are thrilling and fun. Speaking of towns, despite John Adams’s mantra of “independency,” the towns of New England were in fact independent even before the Second Continental Congress convened, over a year before the Declaration of Independence was even a gleam in Jefferson’s eye.

We celebrate this weekend a common declaration of independence, the independence of our ancestors from the most far-flung empire in history (unless one considers ours, today); we wave flags and go to parades, most of which, at least in the small towns, are thrilling and fun. Speaking of towns, despite John Adams’s mantra of “independency,” the towns of New England were in fact independent even before the Second Continental Congress convened, over a year before the Declaration of Independence was even a gleam in Jefferson’s eye.

Adams knew, of course, that New England could not go it alone. His cries were all the more urgent because if the other colonies did not come along (Virginia, especially, which developed a history of seceding quite late) the empire would turn back on New England and systematically annihilate her. Whatever the south would later think of the damn Yankees, were it not for the townsmen of New England there would never have been a republic.

The townsmen did not rise up because of documents, or because they had read Locke. They did it because the imperial government was squeezing the liberty out of them—imposing taxes without their consent, quartering soldiers in their homes, threatening to impose upon them a resident bishop of the Church of England, and, above all, abolishing their town meetings. The townsmen wished no significant change (“How I hate the spirit of innovation,” said John Adams in 1776), but rather insisted upon clinging to the ancient institutions that defined them. Their liberty was resident in their towns and churches and schools and “training fields.” It was passed on though the remarkable interconnection of families (my own is descended from at least a hundred of the families of the Great Migration of 160-41). It was activated politically not only through the town meetings but through the covenants established for every conceivable public purpose, from church-bell ringing to warning the outlying towns that the Regulars were coming.

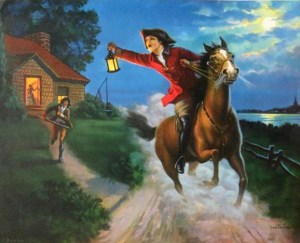

Enter Paul Revere. If you wish to understand the nature of the War for Independence in New England, read David Hackett Fischer’s Paul Revere’s Ride. “Paul Revere and the other riders did not spread the alarm merely by knocking on individual farmhouse doors. The also awakened the institutions of New England…They enlisted its churches and ministers, its physicians and lawyers, its family networks and voluntary associations.” They managed to put between 47 and 55 regiments of volunteers into the field within about nine hours of their rides through the countryside. The people of New England, in other words, literally rose up in defense of their liberty!

This is all the more remarkable because New England was not a warrior culture. True, their idea of gun control was to require every home to possess firearms, and every able-bodied man had to train in the militia on the village green, but they were industrious farmers and merchants and tradesmen and fishermen; the warrior spirit was foreign to their culture. The fury with which they put General Gage and his troops to flight, and eventually caused their evacuation of Boston, is the story of men like Paul Revere.

He was what we would today call an entrepreneur. A tradesman skilled in working with metals, especially silver, he developed business acumen and a network of markets in part because he joined all the covenantal associations that spread outward from his family. His influence grew in Boston because he was good at what he did, and he had a gift for friendship and great energy. He didn’t gain political position because of what he read or what he wrote, but because he could organize and was willing to do the small jobs that needed doing. People trusted him, even to organize the rides that would spread the word to New England that the Regulars were marching on Lexington and Concord.

The rising of the towns was not a surprise to Timothy Dwight, at the time a tutor at Yale. He was the grandson of Jonathan Edwards, an educated and privileged man, and he joined the army as a chaplain just after hostilities broke out. Within a year he was home, finding it necessary to take care of his mother and siblings after his father and several other family members migrated to the Natchez country of Mississippi to avoid having to take sides against the Mother country. Timothy’s father was a patriot, but was also a judge who had taken an oath of loyalty to the King and could not in conscience oppose him. Most of Timothy’s family, including his father, aunt and uncle and several cousins died of fever and he was left to head the family. In New England, family trumped war.

Later on, when he was president of Yale, he published “Greenfield Hill,” a kind of New England Aeneid, wherein he told of the competence of New Englanders in their towns.

Ah! knew he but his happiness, of men

Not the least happy he, who, free from broils,

And base ambition, vain and bustling pomp,

Amid a friendly cure, and competence,

Tastes the pure pleasures of parochial life.

Even later he would ride off into the countryside to visit places in New England and New York, and to write short essays on the towns and hamlets he found. Travels in New England and New York, published after his death in 1818, and again in a wonderful modern edition by Barbara Miller Solomon (4 vols.; Cambridge, 1969), is the richest description of local life ever written about any region or locality in American History.

He often told his graduating seniors: “More free than we are, man with his present character cannot be. If we preserve such freedom, we shall do what never has been done. The only possible means of its preservation, miracles apart, is the preservation of those institutions from which it has been derived.” Family, church, town, voluntary associations—these are not just the “choices” that are available to us, they are the very stuff of freedom. Dwight and all good New Englanders knew that freedom is not something attached or owed to the individual—although individual freedom is highly desirable—it is convenantal (not compactual) and is rooted in the institutions that are part of the Order of Creation.

As we celebrate the documents produced by the generation that also gave us Paul Revere and Timothy Dwight, let us remember that they knew something that we have largely forgotten: the richness of community life that lay behind those documents, and without which they would never have been written.

This essay was first published here in July 2011.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” (1933) by Edward Mason Eggleston, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News