We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were both “Godded-up” to an extreme degree, treated at various times as if they could not err, treatment that author Allen Barra thinks contributed to the fact that neither man ever really grew up.

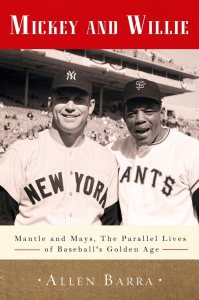

Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Golden Age, By Allen Barra (528 pages, Crown Archetype, 2013)

If you were a writer who could make your living by your pen, what would you write about? Allen Barra makes his living by his pen and he writes primarily about sports. True, there was one book about the history and legends of Wyatt Earp, but the rest are on topics such as the great debates in baseball history, legendary figures like Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and Yankee great Yogi Berra, baseball parks, and football. He is a sports authority, as evidenced by the subtitle of one book: Big Play: Barra on Football. But he also writes occasionally about a Big Writer named Chesterton. I discovered this when I read a 2008 Wall Street Journal piece titled “A Century of ‘Thursday’s,” which marked the centenary of the volume that Chesterton himself called a “melodramatic bit of moonshine.” Barra wrote therein about The Man Who was Thursday as a “phantasmagorical spy story replete with secret identities, sword fights, and more chases than a James Bond movie” that influenced the most various of individuals, including Michael Collins, Jorge Luis Borges, and C. S. Lewis. “Surely no other writer in any century,” Barra observed, “can claim a following that includes Irish rebels, Latin American fabulists and Christian apologists.”

If you were a writer who could make your living by your pen, what would you write about? Allen Barra makes his living by his pen and he writes primarily about sports. True, there was one book about the history and legends of Wyatt Earp, but the rest are on topics such as the great debates in baseball history, legendary figures like Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and Yankee great Yogi Berra, baseball parks, and football. He is a sports authority, as evidenced by the subtitle of one book: Big Play: Barra on Football. But he also writes occasionally about a Big Writer named Chesterton. I discovered this when I read a 2008 Wall Street Journal piece titled “A Century of ‘Thursday’s,” which marked the centenary of the volume that Chesterton himself called a “melodramatic bit of moonshine.” Barra wrote therein about The Man Who was Thursday as a “phantasmagorical spy story replete with secret identities, sword fights, and more chases than a James Bond movie” that influenced the most various of individuals, including Michael Collins, Jorge Luis Borges, and C. S. Lewis. “Surely no other writer in any century,” Barra observed, “can claim a following that includes Irish rebels, Latin American fabulists and Christian apologists.”

Barra would continue to write about Chesterton in the years to come, describing Chesterton as “a writer for all time” and lamenting that he was “praised but unread.” While it might seem unlikely given Chesterton’s unenthusiastic views of spectator sports (with the exception of his positive account of a Notre Dame football game during his visiting lectureship in South Bend), Barra even writes about Chesterton and professional sports in the same book. In Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee, Barra puts many of the famously off-beat Berra-isms beside the words of great thinkers in order to display wisdom behind the wackiness. Thus, Yogi’s “We made too many wrong mistakes” is paired with Chesterton’s “It is human to err; and the only final and deadly error, among all our errors, is denying that we have ever erred.”

OK, the comparison between the quotations is perhaps a stretch, but it’s relevant to Barra’s latest book, Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Golden Age. In the front matter, one of Barra’s epigraphs is the well-known warning of sportswriter Red Smith, “Whatever you do, don’t God-up these guys.” Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were both Godded-up to an extreme degree, treated at various times as if they could not err, treatment that Barra thinks contributed to the fact that neither man ever really grew up. And in the case of Mickey Mantle, the use of alcohol to deal with his celebrity destroyed him.

Barra’s first time at a major league baseball game was a 1961 exhibition between Mantle’s Yankees and Mays’ (then-New York) Giants played in Yankee Stadium. To see the greatest players of a generation playing against each other was a good foundation for a sports fan. Add to this that Barra’s father Alfred, to whom this volume is dedicated, “loved Mickey but worshipped Willie,” and you have a recipe for a lifelong pursuit. This book fulfills a more than fifty-year fascination with two players who defined baseball at its peak as America’s game (a title now belonging to football). Barra’s interest is the odd parallelism of their careers and the interesting divergences of their reputations.

Strictly viewed as players, Barra considers them equals. He lays out the statistical analysis in two appendices where he makes the case that, when measured at their peaks, a) Mantle and Mays are pretty much dead-even with each other as players, and b) they are the greatest players ever.

Interestingly, however, what we learn in the main text is that the Jim Crow-era-Alabama-raised black Mays often had professional advantages over the Okie Mantle. One advantage was health—a bone disease of Mickey’s not only set him back physically, but caused a deferment in military service that led to almost a decade of hostility among certain fans who considered him a draft dodger. Another advantage Mays had was a great deal of professional mentoring from Negro League veterans with whom he started out. Mantle was often on his own, and his long-time coach Casey Stengel was often unaware of how to coach the young star. But Mickey achieved almost as much as Willie did, with many more World Series rings to show.

In the aftermath of their careers, Mickey’s professional reputation failed but he was able to rehabilitate his public persona somewhat more easily than Mays, who was never as charming or open as his friend and competitor. Both men, however, had sad personal endings. Mays’ adopted son and many other family members were largely estranged, while the legacy of Mantle’s alcoholism and promiscuity was an early death for him and broken, alcoholic lives for his wife (whom he left) and his children, most of whom died young.

The parallel that stands out most to me is that neither man grew up with any religious influence nor found it as adults. Barra admits that his own admiration for them was dimmed by knowledge of their personal failings, though the highest regard is still due them as athletes. But the note of sadness in his tale is palpable. Though he doesn’t say it explicitly, Barra’s lesson may be that great players don’t need to be Godded-up. They just need God.

Republished with gracious permission from Gilbert.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News