We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Some weeks ago, I announced to friends on social media that I was asking for privacy to binge-watch the latest season of “Bridgerton” on Netflix.

Judging from their astonished reactions, one would have thought I had announced an affinity for “Keeping Up with the Kardashians,” “The Bachelor,” or “Real Housewives of Miami.” To some, watching “Bridgerton” apparently has marked me as a lowbrow consumer of the brain-rotting, stupefying swill for the masses.

Enjoyable dialogue and plot development all without saying ‘f***’ every third word? Refreshing.

And yet — I’m not embarrassed. Come at me, “Bridgerton” haters! As a onetime English major and a lover of Jane Austen (and of all BBC period/costume dramas), there are plenty of reasons not to be ashamed of enjoying “Bridgerton.” There are even, dare I say it, a few aspects of this gaudy, giddy Netflix offering to admire as positive cultural goods.

For those who have managed to remain ignorant of all things “Bridgerton” since it first premiered in December 2020, here’s a précis to get you up to speed: The streaming series is based on a series of books by author Julia Quinn about an English family in Regency England sometime between 1795 and 1837. Lady Violet, the widowed Viscountess Bridgerton, has eight children to raise and marry off into English society. Each book is about a different Bridgerton child, each of whom is christened in alphabetical order beginning with the letter A and ending with H.

Season one follows the fourth child, Daphne, as she makes her debut in the marriage market of the Ton and sets about finding a titled, suitable husband. Fair warning, there are some spicy scenes (which should surprise no one who has been on a honeymoon). Season two follows the efforts of the eldest son and heir, Anthony, as he sets out to make a practical match but surprises himself by falling in love. Season three stars third son Colin as he falls in love with his childhood friend from across the street, Penelope Featherington, who is hiding a secret of her own.

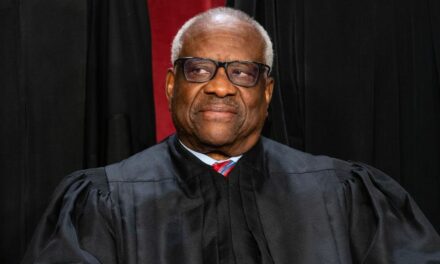

If you’ve gotten this far, you should probably know why people seem to hate “Bridgerton” most: absurd, in-your-face “color-blind” casting. It isn’t even fair to call it color-blind; executive producer Shonda Rhimes made a deliberate decision to boost diversity by casting as many minority actors as possible. There are black lords and earls, interracial couples, pretty Asian and Hispanic debutantes, a black Queen Charlotte wearing an African cloth head-wrap. It’s all completely ahistorical, ludicrous, and initially very distracting for a story set in 19th-century England.

Yet after about 20 minutes of irritation at this heavy-handed agenda, the diverse casting ceases to distract because the story is engaging, fun, and addictive. Period drama purists may continue to be offended, but if it weren’t the color of the actors’ skin, it would probably be the anachronous hairstyles or dialogue. Purists tend to obsess anyway.

Another trouble with this criticism is that every show currently streaming or in theaters now has color-blind casting. In fact, it’s probably impossible and/or illegal to make a movie or television show now without adhering to it.

Netflix and producer Shondaland (Shonda Rhimes’ production company) implemented a mentorship program, “The Ladder and the Producers Inclusion Initiative,” designed specifically to “provide an opportunity for individuals from underrepresented groups to gain onset experience and training” to work as line producers. Under the eligibility requirements for the job posting, applicants must come from “underrepresented communities (e.g., BIPOC).”

Similarly, Amazon Studios has an inclusion policy that requires directors to cast at least one black, “Latinx,” indigenous, Middle Eastern, or Asian character for speaking roles. Beginning in 2024, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will have diversity requirements for Oscar eligibility in the Best Picture category. Films must meet minimum requirements relating to diversity and inclusion to be considered. The guidelines require lead or significant supporting actors, general ensemble cast, or the creative leadership team, among other roles, to be from “historically underrepresented racial or ethnic groups.” So if the color-blind casting in “Bridgerton” is insurmountably annoying to you, I have bad news: It’s not going away any time soon.

If, however, one isn’t single-mindedly devoted to seeking out anachronisms and inaccuracies with which to be irritated, one might notice that “Bridgerton” in fact offers cultural values and practices that are good and worthy of praise in every era.

First, the entire emphasis of the plot is on romance, marriage, (mostly) procreative sex, and children. Big families are admired. Young couples actually want babies. The Bridgerton siblings are affectionate and happy, genuinely enjoy one another’s company, and are without dysfunction. Men and women alike are urged to pursue romance, to marry for love, and to find a partner worthy of mutual respect, commitment, and friendship.

At a time when most of the Western world has a negative birth rate, an emphasis on marriage and children feels necessary and important. Eldest son Anthony marries for love, and the beautiful lady, Miss Sharma, is actually a woman instead of a man in a dress and makeup (I’m looking at you, “Baby Reindeer”).

It’s aesthetically gorgeous. There are wisteria-covered English country homes and elegant Regency architecture. The Bridgerton family’s blue and white salon and well-appointed home is gracious and lovely. The clothing is exquisite — except for the Featheringtons’. Their garish clothing chosen by their scheming villainous Mama (Polly Walker having wonderful fun in this role) is intended to signify their outlier status without the refinements of manners and good taste.

There is an emphasis on art, reading, and Western civilization. Young people are expected to be proficient in music or art and are proud to show off their accomplishments. No one is tattooed, twerking, overdosing, or listening to music with X-rated lyrics. Grand tours of Europe are undertaken so that young people may complete their educations with an appreciation of painting, sculpture, and fashion. Anyone whose sole comprehension of culture and current events comes from TikTok could learn from this.

There is almost no coarse or profane language. Almost every movie and streaming show is now so imbued with the F-word and profanity that its very absence is remarkable. Enjoyable dialogue and plot development all without saying “f***” every third word? Refreshing.

Lastly, “Bridgerton” looks like “Citizen Kane” in comparison to most other current movie or streaming offerings. I refuse to watch another boring Marvel sequel with superheroes in tights and capes going on and on about a multiverse or another dystopian, apocalyptic, Obama-produced, agenda-driven screed about eco-disasters. I’m also weary of real-life media coverage of obese blue-haired women in keffiyehs screaming through a bullhorn before being tear-gassed by police. Perhaps “Bridgerton” is cotton-candy-colored escapism, but one never knows these days whether one’s entertainments will suddenly turn satanic or glorify drug abuse or depict graphic gay rape scenes.

For those concerned that “Bridgerton” might be preachy or degrading simply because the casting protocols toyed with those qualities, rest assured: The story overcomes the activists. Jane Austen knew the social and cultural power of a drawing room drama. In the end, most people simply want their entertainment to be, well, entertaining. And if your idea of entertainment involves beautiful women in tiaras and Empire-waisted satin gowns and men in embroidered waistcoats and jodhpurs falling in love and getting married, is that really so bad? It’s timeless.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News