We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

It’s entirely possible to imagine Theodore Roosevelt becoming president of the United States, even a Rushmore-eligible president, with an entirely different set of female loves. But it’s much less likely.

The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President, by Edward F. O’Keefe. (446 pages, Simon and Schuster, 2024)

Try as he might, Edward O’Keefe, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Library Foundation, fails to dislodge “Mr. Greatheart” as the figure in the life of the first Roosevelt to reach the presidency. “Mr. Greatheart,” of course, was Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., who died when his son was a Harvard freshman. If anyone other than the son himself “created” the twenty-sixth president of the United States, it was his father.

That would be the father who walked his young son night after night as he struggled with asthma. The father who fed him black coffee and cigars. The father who told him repeatedly that he would have to “make your body.” And the father who would hire a substitute to fight for him in the American Civil War.

For that matter, this would also be the father who lived the life of a committed Christian, both spiritually and socially. That commitment was passed along to his son, but only vaguely and certainly without the zeal of the father. In that sense the father may have set an example for the son. He may even have instructed the son and urged the son, but he did not create the son by way of creating Christian zeal in him. That would be the son who proved to be very much a product of an important transformation that began to take place in America in the late nineteenth century.

If anything, the Roosevelt family could be put forth as a prime example of the transformation away from the traditional Christian gospel to the social gospel as preached by any number of Americans, especially progressive Americans, including Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

It might have been the case that the women in the younger Roosevelt’s life could have been instrumental in preserving the traditional Christianity as espoused by the senior Roosevelt. But such does not appear to have been remotely the case.

And just who were these women? Five in particular are featured in these pages. They are his mother, Martha (Mittie), his elder sister, Anna Roosevelt Cowles (Bamie), his younger sister Corine Roosevelt Robinson (Conie), his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, and his second wife, Edith Kermit Carow. Each of them played a significant role in the life of their son, brother and/or husband. Each of them either nurtured him, helped him, influenced him, steered him, berated him, praised him, and/or produced fear in him. But none of them created him. And certainly none of the five replaced the father as a Christian influence on the son.

First and second wives? There was no divorce. Alice Roosevelt, wife of Theodore, and Mittie Roosevelt, mother of Theodore, died on the same day, February 14, 1884, which was two days after the birth of their daughter Alice. At the time, the husband and son thought that the “light had gone out of my life forever.” But shortly thereafter he married Edith Carow, who in all likelihood was the first romantic love of his life, despite his belief that any second marriage was somehow at least faintly immoral.

Much of the book is a straightforward biography of the life of Theodore Roosevelt, and it is a generally praiseful biography at that. Is there room for another such biography? Of course there is. Is there room for a biography with a twist such as this sort of twist? To be sure.

We learn much more about Mittie, who was much more than an empty-headed southern belle. We learn that both sisters were confidantes of sorts. We learn that Bamie played a crucial role in caring for and in many respects virtually raising daughter Alice, who proved to be the daughter whom her father could either run or run the country, but not both at once.

We learn that his first wife, Alice, was not simply the empty-headed New England daughter of wealth, while his second wife, Edith, had been much more than just a neighborhood friend when the two were blooming teenagers and a bit beyond that. Each in one way or another, and to one degree or another, was a genuine love of Theodore Roosevelt. But it’s much too much to insist that any of the five “created” their son, brother, or husband.

It’s entirely possible to imagine Theodore Roosevelt becoming president of the United States, even a Rushmore-eligible president, with an entirely different set of female loves. It’s even possible to imagine the same result with a different father. But it’s much less likely.

Here the example of the father must be emphasized in an entirely different way. Yes, Mr. Greatheart did hire a substitute to fight (and die) in his place during the Civil War. But that is far from the end of the story. He also spent much of the war traveling from Union army camp to Union army camp, urging soldiers to save their money and send it home to their families, rather than waste in by buying liquor and tobacco from what were called sutlers, who were preying on those camps. He also lobbied Congress to hire others to do the work that he was doing, gratis. But the fact that the father did not fight grated on the son.

In fact, it continued to grate well into the son’s adulthood. No doubt that attitude contributed to the son’s decision to fight in the Spanish-American War. That decision was made despite one more fact, namely the serious illness of Edith whose bedside he left for who knew what in Cuba.

“Alone in Cuba” was the sardonic title of a possible TR memoir for his service as a Rough Rider. But there is also little doubt that Roosevelt performed bravely, even courageously, perhaps even foolhardily, in Cuba. Emerging a genuine hero, he had made amends for the failing of his father. He had also paved the way his own for political advancement. In other words, it’s entirely reasonable to conclude that, here again, the father played at least an indirect role in creating a President Roosevelt.

That would be the same Roosevelt whom the bosses of Republican party politics would insert into the race for governor in 1898, while edging aside a sitting, but corruption-plagued, Republican governor. Two years later those same conservative bosses persuaded President William McKinley to fill his vacant vice presidency with the entirely too progressive governor of New York. As one of them put it at the time, “Roosevelt could no more turn down the vice-presidency than stand under Niagara Falls and spit it back up.”

Thanks to an assassin, Vice President Roosevelt became President Roosevelt less than six months into his term. Maybe that would have happened had Mr. Greatheart not hired a substitute. Then again, maybe not.

Much of the remainder of the book deals with the Roosevelt administration in a conventional manner, albeit with a nod in the direction of Mrs. Roosevelt, who felt as though she was “living over the store.” If O’Keefe wants to contend that she had helped create this president, he does not pretend to contend that she had a huge imprint on his presidency.

That stipulated, O’Keefe does note that TR neglected to consult his wife, or perhaps refused to listen to her, when it came to decide whether or not to run for re-election in 1908. The best evidence is that this was entirely his own call. In any event, it proved to be the wrong call. He not only honored his premature pledge not to run, but mistakenly selected William Howard Taft to succeed him.

At least Roosevelt concluded that it had been a mistake by the time he had returned from Africa to challenge the more conservative Taft. The result was the momentous 1912 campaign, a split Republican party and the election of Woodrow Wilson. In a sense, it could be argued that TR indirectly created at least the possibility of the Wilson presidency, thereby assuring the remainder of TR’s life would be highly frustrating, highlighted by President Wilson’s refusal to grant TR permission to organize a regiment of rough riders to fight in the Great War.

O’Keefe deals with these years of frustration very briefly, especially since Roosevelt died in early 1919, having barely reached the age of sixty. Edith survived him by nearly three decades. During most of that time she “reigned at Sagamore Hill,” as “neither the villain nor the saint of the story.”

And quite a story it is, as are the stories of all the women in Theodore Roosevelt’s larger-than-life life, even if they are not necessarily the story of those who “created” a president.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

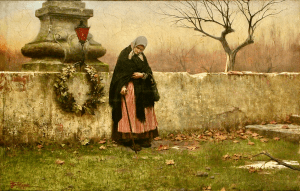

The featured image is the official portrait of First Lady Edith Roosevelt (1902), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News