We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

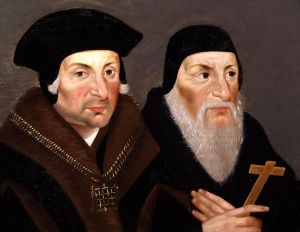

The Catholic Church canonized Saints Thomas More and John Fisher in 1935, only two years after the appearance of “The English Way,” a work edited by one of the most important Christian humanists and publishers of the twentieth century, Maisie Ward, and which looks at the lives, ideas, and deaths of the great Roman Catholic Anglo-Saxons.

The English Way: Studies in English Sanctity from Bede to Newman, edited by Maisie Ward (365 pages, Cluny Media, 2016)

A forgotten book is always a tragedy, but a found book is equally always and everywhere a treasure. There exist exceptions, of course. A book of dark magic or of fascism is best left forgotten, rotting in the cellar of some humid Florida bookstore. But the books that contain truth, beauty, and goodness—these are the books we should never lose.

One of my favorite current Christian Humanists, Canadian Michael O’Brien, has argued in his own masterful novel, Sophia House, that every book that enters the world is akin to the human soul. Some do well, some do ill, and many—simply through the beauty of creation—reflects bits and pieces of divine grace. In essence, when art, a book might very well magnify the Lord.

I have had a book sitting on my shelves for well over a dozen years that I had yet to open. Sadly, I am not alone in treating this book so shabbily and neglecting it so wretchedly. As it turns out, the very copy I own is a 1933 edition that spent most of its life at the Kolbe Memorial Library in Granby, Massachusetts. From what I can tell of the book, no one ever checked out this book. I finally picked up this book that has so patiently waited for me for over a decade. And, what a pleasure. The English Way (Cluny Media, 2016), edited by one of the most important Christian humanists and publishers of the twentieth century, Maisie Ward, and published by the once glorious exemplar of Christian humanist publishing, Sheed and Ward (named after Maisie’s husband and brother), looks at the lives, ideas, and deaths of the great Roman Catholic Anglo-Saxons. Most were saints, but not all. Some who had not yet been recognized as saints soon would be. All, however, served the church with verve. As readily seen in the table of contents, Fathers Gervase Mathew, David Mathew, David Knowles, Bede Jarrett, C. C. Martindale, and Martin D’Arcy, as well as Maisie Ward, Christopher Dawson, E. I. Watkin, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, and Douglas Woodruff each contribute to this work, sometimes twice. Their subjects: Bede; Boniface; Alcuin; Alfred the Great; Wulstan; Aelred; Thomas à Becket; Julian of Norwich; John Fisher; Thomas More; Edmund Campion; Richard Crenshaw; and Cardinal Newman.

In her brief but deep introduction to the book, Ward offers a succinct and satisfying explanation of the Christian humanism behind, above, below, next to, across, and through the work. As Christianity “is universal, it is in every country, but because it is sacramental it is intensely local, found in each country in a special and unique fashion, not a spirit only but a spirit clothed in material form.”

The English Way, therefore, is not the same as the French Way or the German Way. And, with the exception of the contribution from Hilaire Belloc, who lauds the Norman invasion as a critical and happy moment for the English and the Celts as a whole, the authors tend to play up the specifically Anglo-Saxon spirit of English Roman Catholicism.

The English Way, therefore, is not the same as the French Way or the German Way. And, with the exception of the contribution from Hilaire Belloc, who lauds the Norman invasion as a critical and happy moment for the English and the Celts as a whole, the authors tend to play up the specifically Anglo-Saxon spirit of English Roman Catholicism.

In this vein, the book seems downright Tolkienian, though this great mythmaker makes no appearance here. Still a young man and not having published The Hobbit, Tolkien was as yet known only by other British academics. Throughout all of his life and fiction, Tolkien had embraced and promoted the Anglo-Saxon conceptions of law, language, and religion as the highest the world had seen, no matter how ridiculous this idea might seem to twentieth-century Protestant Britons. Whatever the accuracy of Tolkien’s assessment, his views permeated the best selling novel of the twentieth century, The Lord of the Rings, and continue to influence, no matter how covertly, millions of readers every year.

Taking Christian humanism even further, however, that cultural, linguistic, and religious patriotism, The English Way focuses on the contributions of individual human persons, each a unique reflection of the imago Dei. Of course, each writer brings his own personality to the study of the subject personalities. In this sense, this is Christian humanism calling upon Christian humanism, a form of grace calling upon grace, the book itself seemingly sacramental.

Yet, while the book might at first glance appear as merely another twentieth-century piece of pious hagiography, this is far from being the case. The writers sympathize with the plight of each of the individuals discussed, but they do so in such a poetic fashion that the reader simply delights in the immersion into deep Catholicism and the meshing of various personalities. Again, it is hard not to think of Tolkien, that great Anglo-Saxon scholar and myth maker. As he wrote to his great student, W. H. Auden (a convert to Catholicism), each person is an “allegory…each embodying in a particular tale and clothed in the garments of time and place, universal truth and everlasting life.”

In his piece on Alcuin, Douglas Woodruff, always a profound defender of the Western tradition, writes: “Yet there should be a keener sense of filial piety toward the men to whose labours we owe the preservation of Virgil and Cicero, and nearly all the poets and prose writers of ancient Rome.” Yet, Woodruff laments, the modern scholar so rarely gives any time or attention to so great a man as Alcuin.

Unquestionably, at least to me, the best piece is the first of the two by G. K. Chesterton. The great twentieth-century man so capably understood the souls of those who came before him. At his best, he notes, King Alfred

clarified and codified the best laws of the West Saxon tradition; but he became a more important sort of legislator in the moral sphere when he translated Boethius for his people, with very characteristic additions of his own; and so brought into England the full tradition of Europe; the tradition of the Christian creed resting upon the Pagan culture. He had been troubled all his life with a recurrent and rather mysterious disease; and he died at the early age of fifty-two, in the first year of the new century. The night of the barbarian peril was already over, and he died in the dawn.

Alfred, too, gave us the term “Christendom.” A saint, a warrior, a skeptic, and a redeemed believer, Alfred is the great Anglo-Saxon Roman Catholic, a model for all leaders who would follow him over the centuries.

Out of the mouth of the Mother of God

like a little word come I;

For I go gathering Christian men

from sunken paving and ford and fen,

To die in a battle, God knows when,

By God, but I know why.

And this is the word of Mary,

The word of the world’s desire:

“No more of comfort shall ye get,

Save that the sky grows darker yet

and the sea rises higher.”

Then silence sank.

So does Chesterton describe Alfred’s mystical encounter with the Virgin in his epic, The Ballad of the White Horse. That epic poem inspired so many other Christian humanists, including Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Christopher Dawson, and Russell Kirk. Dawson went so far as to explain that the poem shaped his entire view of history, while Kirk spent a considerable amount of his life not only pondering the poem, but memorizing it. As Kirk slipped in and out of consciousness during the last hours of his life, he continued to reflect on the poem, finding new meaning in it only moments before passing into eternity.

While he lived three centuries before St. Thomas Aquinas, Alfred was, for all intents and purposes, the perfect Thomistic king as described and hypothesized in his treatise, On Kingship.

John Fisher, Father David Mathews argues, carried with him a certain innocence and holy naiveté throughout his life, despite the company he kept of royalty and humanists. “The piety and old-fashioned scholarship, the careful fine calligraphy, the controlled appreciation of good letters, would all seem to have marked out Dr. Fisher for a life of learning and quiet pastoral care; the stole, the doctor’s cap; hardly the mitre.”

It is, once again, Chesterton who emerges so successfully in this book. In his second contribution to The English Way, the grand Christian humanist writes about Thomas More. Chesterton presents More as a man of integrity and honor, a man equally capable of mirth, a “man who died laughing.” Whereas scholars divided More into the old and the young, the persecutioner and the persecuted, the writer of Utopia and the chancellor, Chesterton presents him as the complete man, a man of God. “The difference is that England exists, unlike Utopia; and this somewhat eminent Englishman wanted England to continue to exist; and especially the England that he loved.”

The Catholic Church canonized Sts. Thomas More and John Fisher in 1935, only two years after the appearance of The English Way.

The beatification of these two saints is not the only thing that makes the timing of this book meaningful. One could make the fine case that the entire Christian humanist revival and, especially, the Catholic literary revival of the twentieth century originated with Sheed and Ward. Certainly, scholars such as Maritain, Dawson, Chesterton, and Belloc had published before Sheed and Ward came into existence as a press. Yet, it was the vision of Frank Sheed and Maisie Ward that harnessed and promoted the movement from the 1920s through the early 1960s. Their business and personal correspondence now residing at the University of Notre Dame reveals not only their profound and unending love for one another, but also for the Roman Catholic Church and its intellectual, literary, and artistic treasures. In 1929, for example, Sheed encouraged his employee, Tom Burns, to work closely with Dawson. Burns and Dawson has already edited four issues of the mischievous Catholic journal, Order, when Sheed suggested they might do something in book form. The resultant collaboration, A Monument to St. Augustine, brought together the greatest Christian humanists of England and the European continent to celebrate the life and work of St. Augustine on the 1,500th anniversary of his death. With the book an immediate success, Burns and Dawson began the short-lived but immensely influential book series, Essays in Order, featuring the works of Maritain, Dawson, Nicholas Berdyaev, Francois Mauriac, Carl Schmitt, E. I. Watkin, Theodor Haecker, Thomas Gilby, and Herbert Read.

For nearly four decades, as Sheed remembers in his autobiography, The Church and I, they believed they were ushering in a new, reformed, purified, and intellectual Catholicism throughout the Western world. “For the twenties on into the sixties, euphoria reigned among Catholics. We were happy in the Church and confident in its future. Converts were pouring in—up to thirteen thousand in one notable year in England, over thirty thousand a year in the United States.”

It was near the beginning of this euphoric revival that The English Way appeared, immediately after Essays in Order, the centerpiece of Sheed and Ward at the time. Certainly, The English Way appears confident and just, ready to approach a skeptical English-speaking audience with historical, real, and tangible examples of intellectual as well as spiritually-charged Catholics, most of Anglo-Saxon origins.

Why I spotted and rediscovered The English Way just when I did, I have no idea. But I am very glad to have been so blessed. Out of the mouth of the Mother of God… go we.

This essay serves as the Introduction to The English Way (Cluny Media, 2016), and is republished here by gracious permission of the author and Cluny Media. It first appeared here in June 2022.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image, uploaded by Chick Ensemble, is a photograph of the Roman Catholic Church of the English Martyrs. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The portrait of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher (1600s) is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News