We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

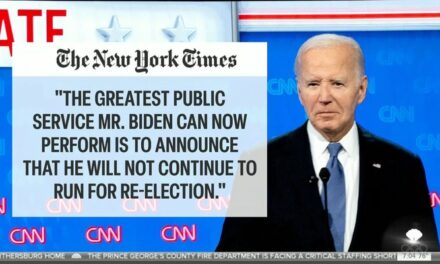

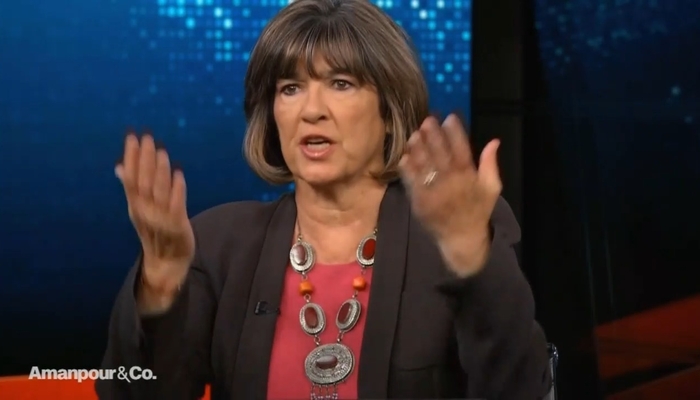

PBS’s Christiane Amanpour likes to say that journalists should be “truthful, not neutral,” but a common theme of Amanpour and Company is that her commitment to the truth only goes one way. For Wednesday’s Juneteenth show, Amanpour claimed that Donald Trump’s presidency and the Supreme Court represent “hurdles” to racial equality, while her guest, Equal Justice Initiative Executive Director Bryan Stevenson, claimed that some states are making it illegal to learn about the history of racial injustice in America.

Amanpour led Stevenson with more of a declaration than a question, “So, let’s talk a little bit about more hurdles that seem to be — I mean, just rushing to get put up by the Supreme Court votes by, you know, certainly under the Trump administration. So, if Congress won’t pass voting rights legislation, Supreme Court won’t uphold current laws, well, obviously, there’s been progress, but there seems to be so much pushback.”

Stevenson gave a long answer that began with him agreeing, “No, you’re absolutely right. We are still in the middle of a really important narrative struggle in the United States for what it means to actually achieve freedom. And I do think the historical context is important. After emancipation, our Congress passed the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection to formerly enslaved people. They passed the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed the right to vote. But those rights were not enforced because we were more committed in America to maintaining racial hierarchy, to maintaining white supremacy than enforcing the rule of law.”

Later in his reply, he recalled that “Now in Berlin, you can’t go 200 meters without seeing markers and stones placed next to the homes of people who were killed during the Holocaust. There’s a landscape that is trying to reckon with the horrors of that. Every student in Germany is required to study the Holocaust. You can’t graduate without that.”

Attempting to contrast that with America, he claimed, “But here in the United States, we have states passing laws trying to make it illegal, impermissible for people to study these histories, and that just speaks to the challenge that we face and so, we are in the middle of it, and we have a lot of work to do, which is why I am persuaded that we need an era of truth and justice, truth and repair, truth and restoration, truth telling about this history.”

That is false, and no matter how many times people like Stevenson repeat it, it will not suddenly become true. The progressive left does not own the legacy of abolitionism, just as Amanpour does not get to claim the mantle of truthfulness in journalism.

Here is a transcript for the June 19 show:

PBS Amanpour and Company

6/19/2024

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk a little bit about more hurdles that seem to be — I mean, just rushing to get put up by the Supreme Court votes by, you know, certainly under the Trump administration. So, if Congress won’t pass voting rights legislation, Supreme Court won’t uphold current laws, well, obviously, there’s been progress, but there seems to be so much pushback.

BRYAN STEVENSON: No, you’re absolutely right. We are still in the middle of a really important narrative struggle in the United States for what it means to actually achieve freedom. And I do think the historical context is important. After emancipation, our Congress passed the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection to formerly enslaved people. They passed the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed the right to vote. But those rights were not enforced because we were more committed in America to maintaining racial hierarchy, to maintaining white supremacy than enforcing the rule of law.

And so, we’ve known for a very long time that law alone will not achieve the kind of justice — the kind of equality that we seek in this country. It took 100 years. Between the late 1860s until that horrific and challenging but triumphant struggle in the 1960s to create a Voting Rights Act, another law designed to enforce these rights. But that narrative of maintaining racial hierarchy, it was still with us.

And even though we passed the civil rights laws in 1964 and the voting rights laws in 1965, there were a lot of people in this country that resisted and rejected the idea that black people should be equal to white people. And that’s why I think the great challenge we face in this country is a narrative challenge.

Yes, we have to have the rule of law, but we also have to push back against these ideas we have inherited that somehow black people are not as good as white people, that black people are less capable, less worthy, less trustworthy. And that’s the fundamental challenge that I believe we have to approach. We never really had the transitional justice that other countries that deal with horrific human rights abuses have had.

In South Africa, there was a process of truth and reconciliation after apartheid collapse. They gave voice to the victims of apartheid to speak to their harm and their injury. And the perpetrators had an opportunity to give voice to their wrongdoing. In Berlin, in Germany, you see a country and a city that engaged in transitional justice.

Now in Berlin, you can’t go 200 meters without seeing markers and stones placed next to the homes of people who were killed during the Holocaust. There’s a landscape that is trying to reckon with the horrors of that. Every student in Germany is required to study the Holocaust. You can’t graduate without that. But here in the United States, we have states passing laws trying to make it illegal, impermissible for people to study these histories, and that just speaks to the challenge that we face and so, we are in the middle of it, and we have a lot of work to do, which is why I am persuaded that we need an era of truth and justice, truth and repair, truth and restoration, truth telling about this history.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News