We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Oh, the many moods and stories Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg conjures in my mind, my heart. There’s the transcendent “Morning Mood” from his Peer Gynt Suite, the haunting yet hopeful “Last Spring.” I’ve sat in my car and wept to the wintry longing in his “Nocturne.” There’s the “March of the Dwarves” that evokes a Warner Bros cartoon so clearly I can almost see three mischievous rabbits bounding through a garden, an angry farmer running after them with his pitchfork. As a ballet dancer, I performed to Grieg’s “Holberg Suites,” which brought forth a story within a story. Then there’s his Piano Concerto in A minor, which is massive, thrilling, stirring, so much of a good thing, we’ll divide Grieg’s music into two essays and save the Piano Concerto for later.

My most unforgettable Grieg-induced mood and memory took place in 1985, in Africa. I was a new Peace Corps trainee, based in Lambaréné, Gabon, and we had a day off training to visit the famed Schweitzer Museum. Two dozen of us, trainees and teachers, loaded into four motor-powered pirogue canoes, and we coasted down the Ogooué River toward the Schweitzer compound. I was homesick, still struggling to reconcile my previous refined world of ballet, classical music and academics, missing it terribly (at least the former two), but I’d brought a dozen cassettes and a small cassette player to Gabon (a setup I elaborated on HERE). On that day I’d brought a Grieg recording of his Peer Gynt Suites. I can’t help but chuckle now at how quirky I must have appeared, determined to play a classical recording in the middle of provincial Africa, in this pirogue on the water, the cassette player smashed up against my ear. I didn’t care. Out blasted “Morning Mood,” and it was simply, utterly gorgeous. The perfect meeting of music, nature and movement. Every time I hear that piece now, I see that afternoon where life was transcendent and perfect (if only for the length of the song).

Give it a listen.

As a creative writer, there’s a hunger in me to spend some time each day in what I could call “the fantasy realm.” Half the time I’m a fiction writer, after all. I create worlds—specific and colorful and fragrant and peopled by vivid personalities—and daily inhabit them as I work on my novels. I crave the trifecta of the natural world, the unseen world, and the stories that inhabit both. Oh, and classical music.

I can’t help but think Grieg did too.

Edvard Hagerup Grieg was born June 15, 1843, in Bergen, Norway, to an established, upper-class family. His father was a prosperous merchant who served as Bergen’s British vice-consul, and his mother, the daughter of a provincial governor, was a gifted musician. Having studied piano, voice and music theory in Hamburg and London, she was quick to note her young son’s interest in music, and started teaching him piano at age six. He proved prodigiously talented. When he was 15, famed Norwegian violin virtuoso, Ole Bull, a family friend and relative (his brother’s wife was Edvard’s aunt), visited the family. He listened to the teenaged Edvard play the piano and told the family, “Get the boy to Leipzig Conservatory—he’s got a big talent.” So they did, where he studied piano under Bohemian piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles, at the conservatory founded 15 years earlier by Felix Mendelssohn, where European musical luminaries like Robert and Clara Schumann had also taught. Edvard spent the next four years there, but bristled against the disciplinary aspect of his training, later admitting that “I was a dreamer, without any talent for the battle of life. I was awkward, sluggish, unattractive, and quite unteachable.” During that time, he also fell ill and was hospitalized with pleurisy, subsequently losing the use of one lung, which would compromise his health through the rest of his life.

After his Leipzig Conservatory years, he returned to Bergen, instantly establishing himself as a fine pianist and competent composer, but within two years had left again, this time to Copenhagen, where he studied with Danish composer, Niels Gade. His stay of two years became formative on several levels. A re-established relationship with his cousin Nina, a concert soprano, grew deeper, concurrent with a close friendship with Rikard Nordraak, a fellow Norwegian who’d written the Norwegian national anthem. Nordraak was similar to Ole Bull, fiercely loyal to all things Norwegian, intent on preserving and incorporating its culture, its natural beauty, in their music-making. Nordraak’s enthusiasm and zeal were contagious, and Grieg found himself turning away from the German Romanticism that the Leipzig Conservatory had instilled in him, and reaching instead for Norway, with its fjords and mountains, its rich folkloric heritage and unique harmonic beauty—the latter courtesy of Norway’s traditional Hardanger fiddle (a fascinating instrument that deserves its own essay, but that you can get a bite-sized taste of information and sound HERE).

The other formative thing about Grieg’s Copenhagen years was a deepening romantic relationship with Nina. Unfortunately, both their families disapproved of the match, even beyond the weirdness (by today’s standards) of marrying one’s first cousin. (His mother and her father were siblings.) Edvard’s father thought it was a mistake for Edvard to add a wife and family to the equation, if he wanted to persevere as a performing and composing musician. Nina’s mother was harsher, saying, “He has nothing, he cannot do anything, and he makes music nobody cares to listen to.” Ouch! But there’s no stopping love, and the two ignored their parents’ reproof, marrying in 1867 (where none of their parents attended).

The ensuing years brought the Griegs fortune and sorrow, like that which can be found in most lives. Edvard’s music garnered positive acclaim and he was one of those fortunate composers who was able to observe for himself his music’s popularity in his lifetime, even as he bristled against the notion that “popular” meant “lesser” in many of the critics’ mind.

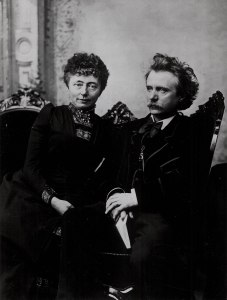

I’ve noticed how many articles describe Grieg in a benevolent, undramatic fashion. One whom, for all his success in Europe as a composer and pianist, was a bit of a homebody, attached to the natural beauty and scenery of his rugged homeland, living quietly with his loyal wife. Nina is referenced as a sort of afterthought, his muse, the woman (and singer) to whom he dedicated most of his songs.

I’ve noticed how many articles describe Grieg in a benevolent, undramatic fashion. One whom, for all his success in Europe as a composer and pianist, was a bit of a homebody, attached to the natural beauty and scenery of his rugged homeland, living quietly with his loyal wife. Nina is referenced as a sort of afterthought, his muse, the woman (and singer) to whom he dedicated most of his songs.

But digging deeper into my research brought more. Now I’m learning about the fire in them both, the passion and dedication to their art forms. Nina, remember, had been professionally trained as a concert soprano, and was a powerful, affecting performer. A year after their marriage, she gave birth to a daughter, Alexandra. Tragically, the baby died at 13 months, from meningitis, and then Nina miscarried around the same time. It must have been beyond devastating for the couple, both having spoken of their wish for a big family. Grieg poignantly wrote to a friend how, “It is hard to watch the hope of one’s life lowered into the earth, and it took time and quiet to recover from the pain, but thank God, if one has something to live for one does not easily fall apart; and art surely has—more than many other things—this soothing power that allays all sorrow.”

Alas, what soothed and comforted Edvard likely didn’t do the same for Nina. She had her grief, her deep sorrow, and surely more than a few demons (if only because being an independent-minded, spirited woman, a performer, in the 1800s was surely a challenge, and she’d just lost her only child). When, in 1875, Edvard’s parents both died, six weeks apart, this surely cemented the realization for Edvard and Nina that their hoped-for family was, and would remain, just the two of them. You’d think this would draw them together, but from 1875 to 1883, theirs was a turbulent marriage that sometimes looked like it was going to go bust.

Author Brendan Ward elaborates on this in his biography, Edvard Grieg: Little Great Man: The unorthodox life of Norway’s greatest composer:

Artistic and personal tensions and a semi-nomadic existence stalked the Grieg marriage. Lack of proper copyright protection and no guarantee of royalties meant most of the couple’s income derived from performances. Whether the Griegs liked it or not, the stage had to be their second home. Both were drawn to it anyway, each with their own strong will and self-belief. It led to antipathy and estrangement.

“Edvard and I lived like cat and dog,” Nina said after her husband’s death. “We were both so unfaithful and both so jealous.” She was rumored to have had an affair with her husband’s brother John, and Edvard, the celebrity composer, strayed into the arms of a young Bergen painter, Leis Schjelderup. His desire to follow her to Paris put his marriage in jeopardy in the early 1880s before close friends mediated a successful reconciliation. However strained their private life, Edvard and Nina could not countenance a public break-up.

Love prevailed, and in 1885, they moved to Troldhaugen, the newly built home just outside Bergen where they would stay until Edvard’s death, 22 years later. If they weren’t able to have Family, with its implied stability and comfort, at least they could have that in a home.

Great time to share one of my favorite Lyric Pieces, “Wedding at Troldhaugen,” which Grieg composed to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary. It is pure, aural joy. The pianist is one of my faves, Norwegian virtuoso Leif Ove Andsnes.

There’s ever so much more to share: Grieg’s various distinguished posts and accomplishments; his reputation as a “miniaturist” and the way he skillfully evokes so much of Norway, and his own life, into his 66 Lyric Pieces, a project he labored over for 34 years, through 10 volumes of songs. And then there’s that glorious Piano Concerto in A minor that I mentioned earlier.

Another essay, then. In the meantime, following are a few more of my faves of his to check out…

And BTW, Troldhaugen is still around, as a museum in Bergen. Been there? I want to know what it’s like! Please share in comments, below!

Republished with gracious permission from The Classical Girl (June 2023).

This essay was first published here in June 2023.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured/top image is a painting of Edvard Grieg by Eilif Peterssen completed in 1891, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The photograph of Nina and Edvard Grieg (c. 1886) comes from the Bergen Public Library and has no known copyright restrictions.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News