We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Writing can simultaneously take a lot out of you—you feel pleasantly exhausted after firing off a big piece of work—and make you feel wondrously light and buoyant. How is this? I think it is because writing is simultaneously work and leisure, a mental strain and a contemplative joy.

We are used to dividing our waking lives into work and leisure. Yet for the professional writer—and more particularly the independent, freelance writer—these two categories are quite blurred and indistinct. According to the philosophers, work is pursued for an end whereas leisure is pursued for its own sake as a serene and contented state of being. Leisure is the goal of labor. As Aristotle states in his Ethics, “We are not-at-leisure in order to be-at-leisure.” But there is a complication when it comes to the writer (and perhaps this applies to those involved in intellectual work more generally), because the writer pursues a form of work that involves contemplation, calm reflection, quietude, and ease—qualities associated with leisure.

This intermingling of work and leisure is a very curious fact, one seldom discussed, and for the writer simultaneously a challenge and a blessing. Leisure has been characterized in negative terms as “a void between periods of work.” That is the exact opposite of what work (and leisure) is for the writer. For the writer, work is leisure and leisure is work, and all of it is simply life.

As a freelance writer, what I do is work, to be sure, yet it doesn’t look much like other forms of work. I forget what writer once said that he had a hard time convincing his wife that, when he was staring out the window, he was working.

Many of the commonplaces about work and leisure simply don’t apply to the writer. “Modern man lacks leisure,” we are told. But the writer has all the leisure in the world. “We are immersed in crowds and shun solitude,” it is said. But the writer consumes his life in solitude. Blaise Pascal famously said wrote “all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” But the writer does nothing but sit quietly in a room alone—that is his occupation and livelihood. It would appear that the writer’s situation is inverted from that of the normal person.

My occupation is one that involves a lot of sitting in leisurely surroundings, studying subjects that interest me and getting ideas down on paper or screen. What is this peculiar form of occupation: is it work? Leisure? A little of both? Maybe a good term for it is serious play, understood as the play of the mind and the spirit.

The writer’s life, then, is a mélange of work and leisure. So unified, so completely of a piece, is your life as a writer that you never really stop formulating your writing, even lying at bed at night. You can go through whole day of writer’s block and inactivity, and then, in the evening, suddenly catch “second wind”—one of the most exhilarating feelings in a writer’s life—and a burst of inspiration and activity ensues. A morning can be passed in the doldrums, and then you read something or have a random thought, and you’re off to the races in the afternoon. This lack of regularity gives the writer’s lifestyle an element of happy surprise, though it can also make your days feel scattered and unpredictable. Hence the need for order and structure (about which more later).

Writing, as most writers can testify, requires a degree of isolation. I need to maintain a tranquility of mind, and in order to have that I must shield myself from things that may disturb my thought processes; my mind must be clear at all times. That usually means seeking absolute solitude. As a writer I find must shut out the outside world, a place which has long ceased to make sense to me in any case. Outside there may be chaos; within the sanctuary of the mind there shall be order and reason.

The tricky thing is that the need for leisurely tranquility can take over one’s entire life. Right now, I am content in my leisure, my serious play. But non-leisure is always encroaching; can I stay ahead of it, evade it?

The life of the writer, though seemingly placid, has its difficulties and challenges like any other occupation. It is not without a subtle disquiet, its own internal drama. For as soon as one has decided on this walk of life, there comes the struggle to maintain the interior fortress, the private kingdom, against outside forces that threaten it.

Leisure is seductive, and little by little the desire for retirement becomes all but total. You become enveloped in a kind of mania of inactivity. And with it comes the dread of ever having the retreat interrupted. Soon the prospect of an appointment becomes a minor threat, something that will take away from time that could be spent arranging my thoughts. I avoid looking at my calendar for fear that I will soon have to do something and thus break my concentration and steal my precious time. In this way, the outside world becomes an obstacle damming up your creative flow.

Is there something morally culpable in this longing for seclusion and leisure? Is it a kind of selfishness? I have asked myself these questions on occasion. But if one’s vocation is to study and write, how can one be blamed for desiring the condition—the only condition—in which this can be pursued? Is it a crime to want to be left alone in one’s room with one’s books? There is so much more to study and learn. Books, as a wise person once said, open door after door after door.

Another challenge of the freelance writer is one of time management. What should I be doing at any given time? When do I know when inspiration will strike? Will this essay get completed? (That is still an open question.) And the basic question: What exactly am I doing at any given time? Am I working or studying or at leisure? There are moments for the writer when this is not exactly clear.

This brings up the larger topic of the search for structure and order. The writer’s life is a continual search for order—order in one’s mind and order in one’s surroundings. The writing freelancer, as a person of leisurely labor, is a self-made person. He is not reliant on being guided and corralled by a fixed schedule, office routines, or direct orders from a boss. This is, once again, both a blessing and a challenge.

The writer must set clear tasks and stick to them, resisting distractions. This is not easy, because the field of the mind keeps expanding, and everything seems to be related to everything else. In the life of leisure, there is a danger of getting lost in the endless array of intellectual goodies and losing sight of the task one is supposed to be doing. Samuel Johnson said that “the greatest part of a writer’s time is spent reading, in order to write; a man will turn over half a library to make one book.” Leisure is grand, but for the writer leisure must eventually turn a profit in the form of a finished product of the mind, a well-formed statement or argument.

The search for organization is a continuous process and can take many forms. There is of course the pressure of deadlines to consider. The freelancer especially must strive for orderly work habits, because there is no boss to keep you on task. I employ a digital timer to divide time into half-hour or hour increments, thus keeping me at my various projects. A five-dollar purchase, it is one of the most valuable things I have ever owned.

And let us not forget copious note-taking. Leonardo da Vinci and Blaise Pascal kept notebooks that became famous. Pascal, you may remember, is the philosopher best known for the book he never wrote. His scattered notes for a work on apologetics became the Pensées, a book he never actually intended anyone to read in its present form. Not least of the virtues of my little notebooks is that they help me keep in contact with good old pen (in my case an extra-fine Pilot Precise) and paper. On them I am constantly scrawling ideas, quotations, things to research, or actual lines of prose I want to use at some time.

Then there is the organization of one’s surroundings. A writer needs a stimulating environment, preferably one containing large quantities of books. My study has the neat feature of walls with built-in book shelves. In the shelves sit scores of books on—well, not on every topic under the sun, but on the small constellation of topics that interest me, among which first and foremost would be religious philosophy, Western civilization, and the arts. On my walls hang art prints, mainly classic landscapes. The sliding storm door opens out onto the outdoors, offering me the stimulating presence of natural beauty. Most important, a prayer corner beckons for spiritual refreshment. I like to think of the study is an all-in-one environment for the active writer: a library as well as a stimulus for creativity and contemplation.

One of my bookshelves is entirely taken up with a set of World Book Encyclopedias from 1957, a hand-me-down from my mother. People have questioned why I continue to keep such an “out of date” item. There are a number of reasons: nostalgia, the quaint style of the entries, their relation to a particular moment in history. One notes that the entries on Catholicism are all signed “F.J.S.”—that would be Fulton J. Sheen. In addition, the writing is exemplary, succinct and clear. I still use the World Book entries for a quick reference on occasion, as when I want an elegant wrap-up of the life of Socrates. And the whole set is in superb condition, not showing its age at all and without a single strip of library tape. I would never dream of getting rid of these encyclopedias.

From time to time my cat saunters in wanting to look out the storm door. She, too, likes to keep abreast of what’s going on in nature, from impending storms to the return of the cardinals and blue jays. I am reminded of William James’s analogy upon observing his pet dog in his study: “Why may we not be in the universe, as our dogs and cats are in our drawingrooms and libraries?” Animal psychologists have posited that cats regard us humans as merely large cats. So, it stands to reason that, as far as my cat is concerned, what I am engaged in is some vaguely defined Boring Big-Cat Stuff. She no more understands my occupation than she can absorb the contents of the World Book. Yet she is also, in her own way, pursuing a life of leisure. Her intent and serene observation of the natural scene certainly looks contemplative.

And on a human level of consciousness, I am always engaged in my own fight to shut out the Boring Big-Cat Stuff so I can retreat to my own zone of contemplation. I try to get practical things out of the way as soon and as quickly as possible so I can sink down completely into serious leisure.

Josef Pieper, the philosopher whose name is closely linked to the study of leisure, stated that “Leisure […] is a mental and spiritual attitude—it is not simply the result of external factors, it is not the inevitable result of spare time, a holiday, a weekend or a vacation. It is, in the first place, an attitude of mind, a condition of the soul.” Endless, unbroken leisure, an unbounded vista of contemplation, a freedom from all Boring Big-Cat Stuff, is the writer’s dream, unfortunately not to be realized in this life (or can it be?).

The writer is a sponge, absorbing anything and everything in reading or life and letting it form his consciousness and bear fruit. One must keep reading, watching, listening, observing. As a writer, you will need to explain to people that when you are watching a movie you are most definitely working.

Because of his sponge-like nature, the writer needs time and space, both precious commodities. Ideas often don’t come fully formed; they must evolve and mature. I call it letting the ideas percolate. Often when beginning an assignment, I don’t really know what I am writing, have no feeling or passion for it; my attitude is bland, indifferent. It can take days of leisure and “percolation” before I finally connect with the topic, “own” it in a true sense, and then the fire is lit. Before that time, the work can be fitful and agonized. Writing may seem like the “high life,” but this doesn’t mean it is always a smooth road to travel.

In my experience, the “percolating” process tends to invade one’s every waking minute, and possibly some of one’s sleeping minutes too. Thought and research takes up just about all your time, and the writer’s work is never done. Being a writer is not a nine-to-five job but a vocation involving the entirety of your being; you must be constantly alert, at the ready for that sudden flash of inspiration, the insight or connection that will allow you to tie your scattered ideas together into a synthesis.

But because this job is open to the transcendent, it’s like living in a perpetual Sabbath of the soul. As all those engaged in head-work know, when things are going well such work does not feel like work, but more like consecrated leisure.

Based as it is on continuous self-formation, writing is not stringently goal-oriented. True, there is the individual work or project (this essay that I am writing, for example, which I am still not sure if I am going to finish). But above and beyond this, writing is a continually unfolding adventure and journey of the mind. One never “finishes,” but only completes one leg of the journey and rests before resuming. As a writer you go wherever the spirit moves you.

One wishes that the movement and flow were constant and effortless. But doubts can creep in. I am sometimes haunted by the vague fear that the world of thought and intellect is not inexhaustible, that objects of the mind are not endlessly forthcoming, that the well of inspiration will run dry and I will eventually reach the end of my thoughts.

Such melancholy fears dissipate in those writerly moments when your mind is pursuing a theme, your horizons seem to expand, and you are filled with creative joy once again. As a writer you are in the business of fashioning for yourself a kind of intellectual and spiritual cosmos, a particular way of seeing things, a repertoire of ideas and themes and insights that are uniquely yours and exist to be shared with others. There is no more elating feeling, especially when you have successfully finished a project.

And a good writer knows when the project is finished, the product well-rounded and complete. I find that when my thoughts start migrating beyond the framework of the essay or commentary I am writing, it is a sign that everything necessary has been said. There will always be another opportunity to essay fresh ideas. So, after releasing your piece into the world, you return to the wonderful world of leisure, there to fish for new riches.

Writing can simultaneously take a lot out of you—you feel pleasantly exhausted after firing off a big piece of work—and make you feel wondrously light and buoyant. How is this? I think it is because writing is simultaneously work and leisure, a mental strain and a contemplative joy. It is a curious lifestyle, but a glorious one, and one I wouldn’t trade for any other way of life.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

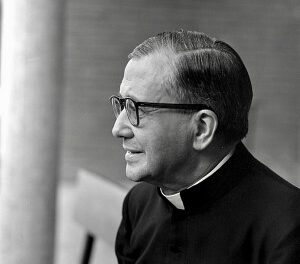

The featured image is “Vsevolod Mikhailovich Garshin” (1884), by Ilya Repin, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News