We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe takes the Gothic setting, with all its machinery and décor, and the preposterous Gothic hero, and transforms them into the material of serious literary art.

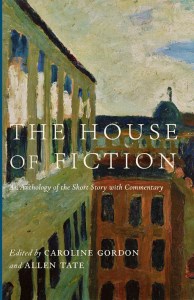

“Commentary on Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher,” from The House of Fiction, edited by Caroline Gordon and Allen Tate (564 pages, Cluny Media)

This famous story is perhaps not Poe’s best, but for the purposes of this book it has significant features which ought to illuminate some of the later, more mature work in the naturalistic-symbolic technique of Flaubert, Joyce, and James. Poe’s insistence upon the unity of effect, from first word to last, in the famous review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales in Graham’s Magazine of May 1842, anticipates from one point of view the high claims of James in his essay “The Art of Fiction.” James asserts that the imaginative writer must take his art at least as seriously as the historian takes his; that is to say, he must no longer apologize, he must not say “it may have happened this way”; he must, since he cannot rely upon the reader’s acceptance of known historical incident, create the illusion of reality, so that the reader may have a “direct impression” of it. It was towards this complete achievement of “direct impression” that Poe was moving, in his tales and in his criticism; he, like Hawthorne, was a great forerunner. The reasons why he did not himself fully achieve it (perhaps less even than Hawthorne) are perceptible in “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

This famous story is perhaps not Poe’s best, but for the purposes of this book it has significant features which ought to illuminate some of the later, more mature work in the naturalistic-symbolic technique of Flaubert, Joyce, and James. Poe’s insistence upon the unity of effect, from first word to last, in the famous review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales in Graham’s Magazine of May 1842, anticipates from one point of view the high claims of James in his essay “The Art of Fiction.” James asserts that the imaginative writer must take his art at least as seriously as the historian takes his; that is to say, he must no longer apologize, he must not say “it may have happened this way”; he must, since he cannot rely upon the reader’s acceptance of known historical incident, create the illusion of reality, so that the reader may have a “direct impression” of it. It was towards this complete achievement of “direct impression” that Poe was moving, in his tales and in his criticism; he, like Hawthorne, was a great forerunner. The reasons why he did not himself fully achieve it (perhaps less even than Hawthorne) are perceptible in “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Like Hawthorne again, Poe seems to have been very little influenced by the common-sense realism of the eighteenth-century English novel. What has been known in our time as the romantic sensibility reached him from two directions: the Gothic tale of Walpole and Monk Lewis, and the poetry of Coleridge. Roderick Usher is a “Gothic” character taken seriously; that is to say, Poe takes the Gothic setting, with all its machinery and décor, and the preposterous Gothic hero, and transforms them into the material of serious literary art. Usher becomes the prototype of the Joycean and Jamesian hero who cannot live in the ordinary world. He has two characteristic traits of this later fictional hero of our own time. First, he is afflicted with the split personality of the manic depressive:

His action was alternately vivacious and sullen. His voice varied rapidly from a tremulous indecision (when the animal spirits seemed utterly in abeyance) to that species of energetic concision… and perfectly modulated guttural utterance, which may be observed in the lost drunkard, or the irreclaimable eater of opium, during the periods of his most intense excitement.

Secondly, certain musical sounds (for some unmusical reason Poe selects the notes of the guitar) are alone tolerable to him: “He suffered from a morbid acuteness of the senses.” He cannot live in the real world; his sensibilities are constantly exacerbated. At the same time he “has a passionate devotion to the intricacies…of musical science”; and his paintings are “pure abstractions” which have “an intensity of intolerable awe.”

Usher is, of course, both our old and our new friend; his new name is Monsieur Teste, and much of the history of modern French literature is in that name. Usher’s “want of moral energy,” along with a hypertrophy of sensibility and intellect in a split personality, places him in the ancestry of Gabriel Conroy, John Marcher, J. Alfred Prufrock, Mrs. Dalloway—a forbear of whose somewhat tawdry accessories they might well be a little ashamed; or they might enjoy a degree of moral complacency in contemplating their own luck in having had greater literary artists than Poe present them to us in a more credible imaginative reality.

We have referred to the Gothic trappings and the poetry of Coleridge as the sources of Poe’s romanticism. In trying to understand the kind of unity of effect that Poe demanded of the writer of fiction we must bear in mind two things. First, unity of plot, the emphasis upon which led him to the invention of the “tale of ratiocination”; but plot is not so necessary to the serious story of moral perversion of which “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “Ligeia,” and “Morelia” are the supreme examples. Secondly, unity of tone (see p. 523), a quality that had not been consciously aimed at in fiction before Poe. It is this particular kind of unity, a poetical rather than a fictional characteristic, which Poe must have got from the Romantic poets, Coleridge especially, and from Coleridge’s criticism as well as “Kubla Khan” and “Christabel.” Unity of plot and tone can exist without the created, active detail which came into this tradition of fiction with Flaubert, to be perfected later by James, Chekhov, and Joyce.

For example, in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” there is not one instance of dramatized detail. Poe’s first person narrator (see p. 507) is in direct contact with the scene, but he merely reports it; he does not show us scene and character in action; it is all description. The closest approach in the entire story to active detail is the glimpse, at the beginning, that the narrator gives us of the furtive doctor as he passes him on “one of the staircases.” If we contrast the remoteness of Poe’s reporting in the entire range of this story with the brilliant recreation of the character of Michael Furey by Gretta Conroy in “The Dead,” we shall be able to form some conception of the advance in the techniques of reality that was achieved in the seventy-odd years between Poe and Joyce. The powerful description of the façade of the House of Usher, as the narrator approaches it, sets up unity of tone, but the description is never woven into the action of the story: the “metaphysical” identity of scene and character reaches our consciousness through lyrical assertion. The fissure in the wall of the house remains an inert symbol of Usher’s split personality. At the climax of the story Poe uses an incredibly clumsy device in the effort to make the collapse of Usher active dramatically; that is, he employs the mechanical device of coincidence. The narrator is reading to Usher the absurd tale of the “Mad Trist” of Sir Launcelot Canning. The knight has slain the dragon and now approaches the “brazen shield,” which falls with tremendous clatter. Usher has been “hearing” it, but what he has been actually hearing is the rending of the lid of his sister Madeline’s coffin and the grating of the iron door of the tomb; until at the end the sister (who has been in a cataleptic trance) stands outside Usher’s door. The door opens; she stands before them. The narrator flees and the House of Usher, collapsing, sinks forever with its master into the waters of the “tarn.”

The Discovery (see p. 519) in this story is, doubtless, the narrator’s revelation that Usher is mad. The Complication (see p. 519) is Usher’s condition and the Resolution the emergence into real life of the fantasies which at the beginning of the story were harbored in Usher’s sick brain. The Peripety is the lady Madeline’s escape from her tomb at a certain moment.

We could dwell upon the symbolism (see p. 524) of the identity of house and master, of the burial alive of Madeline, of the fissure in the wall of the house and the fissure in the psyche of Usher. What we should emphasize here is the dominance of symbolism over its visible base: symbolism external and “lyrical,” not intrinsic and dramatic. The active structure of the story is mechanical and thus negligible; but its lyrical structure is impressive. Poe’s plots seem most successful when the reality of scene and character is of secondary importance in the total effect; that is, in the tale of “ratiocination.” He seemed unable to combine incident with his gift for “insight symbolism”; as a result his symbolic tales are insecurely based upon scenic reality. But the insight was great. In Roderick Usher, as we have said, we get for the first time the archetypal hero of modern fiction. In the history of literature the discoverer of the subject is almost never the perfecter of the techniques for making the subject real.

Editors Caroline Gordon (1895–1981) and Allen Tate (1899–1979) were American literary critics and a novelist and poet, respectively. Married in 1925, they both became Roman Catholics. Their literary contributions earned each of them prominent places in the Southern Renaissance; Robert Penn Warren praised Gordon for “enriching our literature uniquely” and T. S. Eliot recognized Tate, in his time, as one of America’s best poets.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News